PHMSA Final Rule: Hazmat Harmonization With International Standards

PHMSA is amending the Hazardous Materials Regulations (HMR) to maintain alignment with international regulations and standards by adopting various amendments, including changes to proper shipping names, hazard classes, packing groups, special provisions, packaging authorizations, air transport quantity limitations, and vessel stowage requirements. PHMSA is also withdrawing the unpublished November 28, 2022, Notice of Enforcement Policy Regarding International Standards on the use of select updated international standards in complying with the HMR during the pendency of this rulemaking.

DATES:

Effective date: This rule is effective May 10, 2024.

Voluntary compliance date: January 1, 2023.

Delayed compliance date: April 10, 2025.

This final rule is published in the Federal Register April 10, 2024.

View final rule.

| §171.7 Reference material. | ||

| (t)(1), (v)(2), and (w)(32) through (81) | Revised | View text |

| (w)(82) through (92) | Added | View text |

| (aa)(3) and (dd)(1) through (4) | Revised | View text |

| §171.12 North American shipments. | ||

| (a)(4)(iii) | Revised | View text |

| §171.23 Requirements for specific materials and packagings transported under the ICAO technical instructions, IMDG code, Transport Canada TDG regulations, or the IAEA regulations. | ||

| (a)(3) | Revised | View text |

| §171.25 Additional requirements for the use of the IMDG code. | ||

| (c)(3) and (4) | Revised | View text |

| (c)(5) | Added | View text |

| §172.101 Purpose and use of the hazardous materials table. | ||

| Section heading | Revised | View text |

| (c)(12)(ii) | Revised | View text |

| Hazardous materials table, multiple entries | Revised, added, removed | View text |

| §172.102 Special provisions. | ||

| (c)(1) special provisions 78, 156, and 387 | Revised | View text |

| (c)(1) special provisions 396 and 398 | Added | View text |

| (c)(1) special provision 421 | Removed and reserved | View text |

| (c)(2) special provision A54 | Revised | View text |

| (c)(2) special provisions A224 and A225 | Added | View text |

| (c)(4) Table 2—IP Codes, special provision IP15 | Revised | View text |

| (c)(4) Table 2—IP Codes, special provision IP22 | Added | View text |

| §173.4b De minimis exceptions. | ||

| (b)(1) | Revised | View text |

| §173.21 Forbidden materials and packages. | ||

| (f) introductory text, (f)(1), and (f)(2) | Revised | View text |

| §173.27 General requirements for transportation by aircraft. | ||

| (f)(2)(i)(D) | Revised | View text |

| §173.124 Class 4, Divisions 4.1, 4.2 and 4.3— Definitions. | ||

| (a)(4)(iv) | Removed | View text |

| §173.137 Class 8—Assignment of packing group. | ||

| Introductory text | Revised | View text |

| §173.151 Exceptions for Class 4. | ||

| (d) introductory text | Revised | View text |

| §173.167 ID8000 consumer commodities. | ||

| Entire section | Revised | View text |

| §173.185 Lithium cells and batteries. | ||

| (a)(3) introductory text and (a)(3)(x) | Revised | View text |

| (a)(5) | Added | View text |

| (b)(3)(iii)(A) and (B) | Revised | View text |

| (b)(3)(iii)(C) | Added | View text |

| (b)(4)(ii) and (iii) | Revised | View text |

| (b)(4)(iv) | Added | View text |

| (b)(5), (c)(3) through (5), and (e)(5) through (7) | Revised | View text |

| §173.224 Packaging and control and emergency temperatures for self-reactive materials. | ||

| (b)(4) | Revised | View text |

| Table following (b)(7) | Revised | View text |

| §173.225 Packaging requirements and other provisions for organic peroxides. | ||

| Table 1 to paragraph (c) | Revised | View text |

| Table following paragraph (d) | Retitled | View text |

| Table following paragraph (g) | Revised | View text |

| §173.232 Articles containing hazardous materials, n.o.s. | ||

| (h) | Added | View text |

| §173.301b Additional general requirements for shipment of UN pressure receptacles. | ||

| (c)(1), (c)(2)(ii) through (iv), (d)(1), and (f) | Revised | View text |

| §173.302b Additional requirements for shipment of non-liquefied (permanent) compressed gases in UN pressure receptacles. | ||

| (g) | Added | View text |

| §173.302c Additional requirements for the shipment of adsorbed gases in UN pressure receptacles. | ||

| (k) | Revised | View text |

| §173.311 Metal Hydride Storage Systems. | ||

| Entire section | Revised | View text |

| §175.1 Purpose, scope, and applicability. | ||

| (e) | Added | View text |

| §175.10 Exceptions for passengers, crewmembers, and air operators. | ||

| (a) introductory text, (a)(14) introductory text, (a)(15)(v)(A), (a)(15)(vi)(A), (a)(17)(ii)(C), (a)(18) introductory text, and (a)(26) introductory text | Revised | View text |

| §175.33 Shipping paper and information to the pilot-in-command. | ||

| (a)(13)(iii) | Revised | View text |

| §178.37 Specification 3AA and 3AAX seamless steel cylinders. | ||

| (j) | Revised | View text |

| §178.71 Specifications for UN pressure receptacles. | ||

| (f)(4), (g), (i), (k)(1)(i) and (ii), (m), and (n) | Revised | View text |

| §178.75 Specifications for MEGCs. | ||

| (d)(3) introductory text and paragraphs (d)(3)(i) through (iii) | Revised | View text |

| §178.609 Test requirements for packagings for infectious substances. | ||

| (d)(2) | Revised | View text |

| §178.706 Standards for rigid plastic IBCs. | ||

| (c)(3) | Revised | View text |

| §178.707 Standards for composite IBCs. | ||

| (c)(3)(iii) | Revised | View text |

| §180.207 Requirements for requalification of UN pressure receptacles. | ||

| (d)(3) and (5) | Revised | View text |

| (d)(8) | Added | View text |

Previous Text

§171.7 Reference material.

* * * * *

(t) * * *

(1) ICAO Doc 9284. Technical Instructions for the Safe Transport of Dangerous Goods by Air (ICAO Technical Instructions), 2021-2022 Edition, copyright 2020; into §§171.8; 171.22 through 171.24; 172.101; 172.202; 172.401; 172.407; 172.512; 172.519; 172.602; 173.56; 173.320; 175.10, 175.33; 178.3.

* * * * *

(v) * * *

(2) International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code (IMDG Code), Incorporating Amendment 40-20 (English Edition), (Volumes 1 and 2), 2020 Edition, copyright 2020; into §§171.22; 171.23; 171.25; 172.101; 172.202; 172.203; 172.401; 172.407; 172.502; 172.519; 172.602; 173.21; 173.56; 176.2; 176.5; 176.11; 176.27; 176.30; 176.83; 176.84; 176.140; 176.720; 176.906; 178.3; 178.274.

(w) * * *

(32) ISO 9809-2:2000(E): Gas cylinders—Refillable seamless steel gas cylinders—Design, construction and testing—Part 2: Quenched and tempered steel cylinders with tensile strength greater than or equal to 1 100 MPa., First edition, June 2000, into §§178.71; 178.75.

(33) ISO 9809-2:2010(E): Gas cylinders—Refillable seamless steel gas cylinders—Design, construction and testing—Part 2: Quenched and tempered steel cylinders with tensile strength greater than or equal to 1100 MPa., Second edition, 2010-04-15, into §§178.71; 178.75.

(34) ISO 9809-3:2000(E): Gas cylinders—Refillable seamless steel gas cylinders—Design, construction and testing—Part 3: Normalized steel cylinders, First edition, December 2000, into §§178.71; 178.75.

(35) ISO 9809-3:2010(E): Gas cylinders—Refillable seamless steel gas cylinders—Design, construction and testing—Part 3: Normalized steel cylinders, Second edition, 2010-04-15, into §§178.71; 178.75.

(36) ISO 9809-4:2014(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable seamless steel gas cylinders—Design, construction and testing—Part 4: Stainless steel cylinders with an Rm value of less than 1 100 MPa, First edition, 2014-07-15, into §§178.71; 178.75.

(37) ISO 9978:1992(E)—Radiation protection—Sealed radioactive sources—Leakage test methods. First Edition, (February 15, 1992), into §173.469.

(38) ISO 10156:2017(E), Gas cylinders—Gases and gas mixtures—Determination of fire potential and oxidizing ability for the selection of cylinder valve outlets, Fourth edition, 2017-07; into §173.115.

(39) ISO 10297:1999(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable gas cylinder valves—Specification and type testing, First Edition, 1995-05-01; into §§173.301b; 178.71.

(40) ISO 10297:2006(E), Transportable gas cylinders—Cylinder valves—Specification and type testing, Second Edition, 2006-01-15; into §§173.301b; 178.71.

(41) ISO 10297:2014(E), Gas cylinders—Cylinder valves—Specification and type testing, Third Edition, 2014-07-15; into §§173.301b; 178.71.

(42) ISO 10297:2014/Amd 1:2017(E), Gas cylinders—Cylinder valves—Specification and type testing—Amendment 1: Pressure drums and tubes, Third Edition, 2017-03; into §§173.301b; 178.71.

(43) ISO 10461:2005(E), Gas cylinders—Seamless aluminum-alloy gas cylinders—Periodic inspection and testing, Second Edition, 2005-02-15 and Amendment 1, 2006-07-15; into §180.207.

(44) ISO 10462:2013(E), Gas cylinders—Acetylene cylinders—Periodic inspection and maintenance, Third edition, 2013-12-15; into §180.207.

(45) ISO 10692-2:2001(E), Gas cylinders—Gas cylinder valve connections for use in the micro-electronics industry—Part 2: Specification and type testing for valve to cylinder connections, First Edition, 2001-08-01; into §§173.40; 173.302c.

(46) ISO 11114-1:2012(E), Gas cylinders—Compatibility of cylinder and valve materials with gas contents—Part 1: Metallic materials, Second edition, 2012-03-15; into §§172.102; 173.301b; 178.71.

(47) ISO 11114-1:2012/Amd 1:2017(E), Gas cylinders—Compatibility of cylinder and valve materials with gas contents—Part 1: Metallic materials—Amendment 1, Second Edition, 2017-01; into §§172.102; 173.301b; 178.71.

(48) ISO 11114-2:2013(E), Gas cylinders—Compatibility of cylinder and valve materials with gas contents—Part 2: Non-metallic materials, Second edition, 2013-04; into §§173.301b; 178.71.

(49) ISO 11117:1998(E): Gas cylinders—Valve protection caps and valve guards for industrial and medical gas cylinders—Design, construction and tests, First edition, 1998-08-01; into §173.301b.

(50) ISO 11117:2008(E): Gas cylinders—Valve protection caps and valve guards—Design, construction and tests, Second edition, 2008-09-01; into §173.301b.

(51) ISO 11117:2008/Cor.1:2009(E): Gas cylinders—Valve protection caps and valve guards—Design, construction and tests, Technical Corrigendum 1, 2009-05-01; into §173.301b.

(52) ISO 11118(E), Gas cylinders—Non-refillable metallic gas cylinders—Specification and test methods, First edition, October 1999; into §178.71.

(53) ISO 11118:2015(E), Gas cylinders—Non-refillable metallic gas cylinders—Specification and test methods, Second edition, 2015-09-15; into §§173.301b; 178.71.

(54) ISO 11119-1(E), Gas cylinders—Gas cylinders of composite construction—Specification and test methods—Part 1: Hoop-wrapped composite gas cylinders, First edition, May 2002; into §178.71.

(55) ISO 11119-1:2012(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable composite gas cylinders and tubes—Design, construction and testing—Part 1: Hoop wrapped fibre reinforced composite gas cylinders and tubes up to 450 l, Second edition, 2012-08-01; into §§178.71; 178.75.

(56) ISO 11119-2(E), Gas cylinders—Gas cylinders of composite construction—Specification and test methods—Part 2: Fully wrapped fibre reinforced composite gas cylinders with load-sharing metal liners, First edition, May 2002; into §178.71.

(57) ISO 11119-2:2012(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable composite gas cylinders and tubes—Design, construction and testing—Part 2: Fully wrapped fibre reinforced composite gas cylinders and tubes up to 450 l with load-sharing metal liners, Second edition, 2012-07-15; into §§178.71; 178.75.

(58) ISO 11119-2:2012/Amd.1:2014(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable composite gas cylinders and tubes—Design, construction and testing—Part 2: Fully wrapped fibre reinforced composite gas cylinders and tubes up to 450 l with load-sharing metal liners, Amendment 1, 2014-08-15; into §§178.71; 178.75.

(59) ISO 11119-3(E), Gas cylinders of composite construction—Specification and test methods—Part 3: Fully wrapped fibre reinforced composite gas cylinders with non-load-sharing metallic or non-metallic liners, First edition, September 2002; into §178.71.

(60) ISO 11119-3:2013(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable composite gas cylinders and tubes—Design, construction and testing—Part 3: Fully wrapped fibre reinforced composite gas cylinders and tubes up to 450 l with non-load-sharing metallic or non-metallic liners, Second edition, 2013-04-15; into §§178.71; 178.75.

(61) ISO 11119-4:2016(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable composite gas cylinders—Design, construction and testing—Part 4: Fully wrapped fibre reinforced composite gas cylinders up to 150 L with load-sharing welded metallic liners, First Edition, 2016-02-15; into §§178.71; 178.75.

(62) ISO 11120(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable seamless steel tubes of water capacity between 150 l and 3000 l—Design, construction and testing, First edition, 1999-03; into §§178.71; 178.75.

(63) ISO 11120:2015(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable seamless steel tubes of water capacity between 150 l and 3000 l—Design, construction and testing, Second Edition, 2015-02-01; into §§178.71; 178.75.

(64) ISO 11513:2011(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable welded steel cylinders containing materials for sub-atmospheric gas packaging (excluding acetylene)—Design, construction, testing, use and periodic inspection, First edition, 2011-09-12; into §§173.302c; 178.71; 180.207.

(65) ISO 11621(E), Gas cylinders—Procedures for change of gas service, First edition, April 1997; into §§173.302, 173.336, 173.337.

(66) ISO 11623(E), Transportable gas cylinders—Periodic inspection and testing of composite gas cylinders, First edition, March 2002; into §180.207.

(67) ISO 11623(E):2015, Gas cylinders—Composite construction—Periodic inspection and testing, Second edition, 2015-12-01; into §180.207.

(68) ISO 13340:2001(E), Transportable gas cylinders—Cylinder valves for non-refillable cylinders—Specification and prototype testing, First edition, 2004-04-01; into §§173.301b; 178.71.

(69) ISO 13736:2008(E), Determination of flash point—Abel closed-cup method, Second Edition, 2008-09-15; into §173.120.

(70) ISO 14246:2014(E), Gas cylinders—Cylinder valves—Manufacturing tests and examination, Second Edition, 2014-06-15; into §178.71.

(71) ISO 14246:2014/Amd 1:2017(E), Gas cylinders—Cylinder valves—Manufacturing tests and examinations—Amendment 1, Second Edition, 2017-06; into §178.71.

(72) ISO 16111:2008(E), Transportable gas storage devices—Hydrogen absorbed in reversible metal hydride, First Edition, 2008-11-15; into §§173.301b; 173.311; 178.71.

(73) ISO 16148:2016(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable seamless steel gas cylinders and tubes—Acoustic emission examination (AT) and follow-up ultrasonic examination (UT) for periodic inspection and testing, Second Edition, 2016-04-15; into §180.207.

(74) ISO 17871:2015(E), Gas cylinders—Quick-release cylinder valves—Specification and type testing, First Edition, 2015-08-15; into §173.301b.

(75) ISO 17879: 2017(E), Gas cylinders—Self-closing cylinder valves—Specification and type testing, First Edition, 2017-07; into §§173.301b; 178.71.

(76) ISO 18172-1:2007(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable welded stainless steel cylinders—Part 1: Test pressure 6 MPa and below, First Edition, 2007-03-01; into §178.71.

(77) ISO 20475:2018(E), Gas cylinders—Cylinder bundles—Periodic inspection and testing, First Edition, 2018-02; into §180.207.

(78) ISO 20703:2006(E), Gas cylinders—Refillable welded aluminum-alloy cylinders—Design, construction and testing, First Edition, 2006-05-01; into §178.71.

(79) ISO 21172-1:2015(E), Gas cylinders—Welded steel pressure drums up to 3000 litres capacity for the transport of gases—Design and construction—Part 1: Capacities up to 1000 litres, First edition, 2015-04-01; into §178.71.

(80) ISO 22434:2006(E), Transportable gas cylinders—Inspection and maintenance of cylinder valves, First Edition, 2006-09-01; into §180.207.

(81) ISO/TR 11364:2012(E), Gas cylinders—Compilation of national and international valve stem/gas cylinder neck threads and their identification and marking system, First Edition, 2012-12-01; into §178.71.

* * * * *

(aa) * * *

(3) OECD Guideline for the Testing of Chemicals 431 (Test No. 431): In vitro skin corrosion: reconstructed human epidermis (RHE) test method, adopted 29 July 2016; into §173.137.

* * * * *

(dd) * * *

(1) Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, Model Regulations (UN Recommendations), 21st revised edition, copyright 2019; into §§171.8; 171.12; 172.202; 172.401; 172.407; 172.502; 172.519; 173.22; 173.24; 173.24b; 173.40; 173.56; 173.192; 173.302b; 173.304b; 178.75; 178.274; as follows:

(i) Volume I, ST/SG/AC.10.1/21/Rev.21 (Vol. I).

(ii) Volume II, ST/SG/AC.10.1/21/Rev.21 (Vol. II).

(2) Manual of Tests and Criteria (UN Manual of Tests and Criteria), 7th revised edition, ST/SG/AC.10/11/Rev.7, copyright 2019; into §§171.24, 172.102; 173.21; 173.56 through 173.58; 173.60; 173.115; 173.124; 173.125; 173.127; 173.128; 173.137; 173.185; 173.220; 173.221; 173.224; 173.225; 173.232; part 173, appendix H; 175.10; 176.905; 178.274.

(3) Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), 8th revised edition, ST/SG/AC.10/30/Rev.8, copyright 2019; into §172.401.

(4) Agreement concerning the International Carriage of Dangerous Goods by Road (ADR), copyright 2020; into §171.8; §171.23 as follows: [Change Notice][Previous Text]

(i) Volume I, ECE/TRANS/300 (Vol. I).

(ii) Volume II, ECE/TRANS/300 (Vol. II).

(iii) Corrigendum, ECE/TRANS/300 (Corr. 1).

* * * * *

§171.12 North American shipments.

* * * * *

(a) * * *

(4) * * *

(iii) Authorized CRC, BTC, CTC or TC specification cylinders that correspond with a DOT specification cylinder are as follows:

| TC | DOT (some or all of these specifications may instead be marked with the prefix ICC) | CTC (some or all of these specifications may instead be marked with the prefix BTC or CRC) |

|---|---|---|

| TC-3AM | DOT-3A [ICC-3] | CTC-3A |

| TC-3AAM | DOT-3AA | CTC-3AA |

| TC-3ANM | DOT-3BN | CTC-3BN |

| TC-3EM | DOT-3E | CTC-3E |

| TC-3HTM | DOT-3HT | CTC-3HT |

| TC-3ALM |

DOT-3AL

DOT-3B |

CTC-3AL

CTC-3B |

| TC-3AXM | DOT-3AX | CTC-3AX |

| TC-3AAXM |

DOT-3AAX

DOT-3A480X |

CTC-3AAX

CTC-3A480X |

| TC-3TM | DOT-3T | |

| TC-4AAM33 | DOT-4AA480 | CTC-4AA480 |

| TC-4BM | DOT-4B | CTC-4B |

| TC-4BM17ET | DOT-4B240ET | CTC-4B240ET |

| TC-4BAM | DOT-4BA | CTC-4BA |

| TC-4BWM | DOT-4BW | CTC-4BW |

| TC-4DM | DOT-4D | CTC-4D |

| TC-4DAM | DOT-4DA | CTC-4DA |

| TC-4DSM | DOT-4DS | CTC-4DS |

| TC-4EM | DOT-4E | CTC-4E |

| TC-39M | DOT-39 | CTC-39 |

| TC-4LM |

DOT-4L

DOT-8 DOT-8AL |

CTC-4L

CTC-8 CTC-8AL |

* * * * *

§171.23 Requirements for specific materials and packagings transported under the ICAO technical instructions, IMDG code, Transport Canada TDG regulations, or the IAEA regulations.

(a) * * *

(3) Pi-marked pressure receptacles. Pressure receptacles that are marked with a pi mark in accordance with the European Directive 2010/35/EU (IBR, see §171.7) on transportable pressure equipment (TPED) and that comply with the requirements of Packing Instruction P200 or P208 and 6.2 of the ADR (IBR, see §171.7) concerning pressure relief device use, test period, filling ratios, test pressure, maximum working pressure, and material compatibility for the lading contained or gas being filled, are authorized as follows:

(i) Filled pressure receptacles imported for intermediate storage, transport to point of use, discharge, and export without further filling; and

(ii) Pressure receptacles imported or domestically sourced for the purpose of filling, intermediate storage, and export.

(iii) The bill of lading or other shipping paper must identify the cylinder and include the following certification: “This cylinder (These cylinders) conform(s) to the requirements for pi-marked cylinders found in 171.23(a)(3).”

* * * * *

§171.25 Additional requirements for the use of the IMDG code.

* * * * *

(c) * * *

(3) Except as specified in this subpart, for a material poisonous (toxic) by inhalation, the T Codes specified in Column 13 of the Dangerous Goods List in the IMDG Code may be applied to the transportation of those materials in IM, IMO and DOT Specification 51 portable tanks, when these portable tanks are authorized in accordance with the requirements of this subchapter; and

(4) No person may offer an IM or UN portable tank containing liquid hazardous materials of Class 3, PG I or II, or PG III with a flash point less than 100°F (38°C); Division 5.1, PG I or II; or Division 6.1, PG I or II, for unloading while it remains on a transport vehicle with the motive power unit attached, unless it conforms to the requirements in §177.834(o) of this subchapter.

* * * * *

§172.101 Purpose and use of hazardous materials table.

* * * * *

(c) * * *

(12) * * *

(ii) Generic or n.o.s. descriptions. If an appropriate technical name is not shown in the Table, selection of a proper shipping name shall be made from the generic or n.o.s. descriptions corresponding to the specific hazard class, packing group, hazard zone, or subsidiary hazard, if any, for the material. The name that most appropriately describes the material shall be used; e.g, an alcohol not listed by its technical name in the Table shall be described as “Alcohol, n.o.s.” rather than “Flammable liquid, n.o.s.”. Some mixtures may be more appropriately described according to their application, such as “Coating solution” or “Extracts, flavoring, liquid”, rather than by an n.o.s. entry, such as “Flammable liquid, n.o.s.” It should be noted, however, that an n.o.s. description as a proper shipping name may not provide sufficient information for shipping papers and package markings. Under the provisions of subparts C and D of this part, the technical name of one or more constituents which makes the product a hazardous material may be required in association with the proper shipping name.

* * * * *

§172.102 Special provisions.

* * * * *

(c) * * *

(1) * * *

(78) This entry may not be used to describe compressed air which contains more than 23.5 percent oxygen. Compressed air containing greater than 23.5 percent oxygen must be shipped using the description ‘‘Compressed gas, oxidizing, n.o.s., UN3156.’’

* * * * *

(156) Asbestos that is immersed or fixed in a natural or artificial binder material, such as cement, plastic, asphalt, resins or mineral ore, or contained in manufactured products is not subject to the requirements of this subchapter.

* * * * *

(387) When materials are stabilized by temperature control, the provisions of §173.21(f) of this subchapter apply. When chemical stabilization is employed, the person offering the material for transport shall ensure that the level of stabilization is sufficient to prevent the material as packaged from dangerous polymerization at 50°C (122°F). If chemical stabilization becomes ineffective at lower temperatures within the anticipated duration of transport, temperature control is required and is forbidden by aircraft. In making this determination factors to be taken into consideration include, but are not limited to, the capacity and geometry of the packaging and the effect of any insulation present, the temperature of the material when offered for transport, the duration of the journey, and the ambient temperature conditions typically encountered in the journey (considering also the season of year), the effectiveness and other properties of the stabilizer employed, applicable operational controls imposed by regulation (e.g., requirements to protect from sources of heat, including other cargo carried at a temperature above ambient) and any other relevant factors. The provisions of this special provision will be effective until January 2, 2023, unless we terminate them earlier or extend them beyond that date by notice of a final rule in the Federal Register.

* * * * *

(421) This entry will no longer be effective on January 2, 2023, unless we terminate it earlier or extend it beyond that date by notice of a final rule in the Federal Register.

* * * * *

(2) * * *

A54 Irrespective of the quantity limits in Column 9B of the §172.101 table, a lithium battery, including a lithium battery packed with, or contained in, equipment that otherwise meets the applicable requirements of §173.185, may have a mass exceeding 35 kg if approved by the Associate Administrator prior to shipment.

* * * * *

(4) * * *

IP15 For UN2031 with more than 55% nitric acid, the permitted use of rigid plastic IBCs, and the inner receptacle of composite IBCs with rigid plastics, shall be two years from their date of manufacture.

* * * * *

§173.4b De minimis exceptions.

* * * * *

(b) * * *

(1) The specimens are:

(i) Wrapped in a paper towel or cheesecloth moistened with alcohol or an alcohol solution and placed in a plastic bag that is heat-sealed. Any free liquid in the bag must not exceed 30 mL; or

(ii) Placed in vials or other rigid containers with no more than 30 mL of alcohol or alcohol solution. The containers are placed in a plastic bag that is heat-sealed;

* * * * *

§173.21 Forbidden materials and packages.

* * * * *

(f) A package containing a material which is likely to decompose with a self-accelerated decomposition temperature (SADT) of 50°C (122 °F) or less, or polymerize at a temperature of 54°C (130 °F) or less with an evolution of a dangerous quantity of heat or gas when decomposing or polymerizing, unless the material is stabilized or inhibited in a manner to preclude such evolution. The SADT may be determined by any of the test methods described in Part II of the UN Manual of Tests and Criteria (IBR, see §171.7 of this subchapter).

(1) A package meeting the criteria of paragraph (f) of this section may be required to be shipped under controlled temperature conditions. The control temperature and emergency temperature for a package shall be as specified in the table in this paragraph based upon the SADT of the material. The control temperature is the temperature above which a package of the material may not be offered for transportation or transported. The emergency temperature is the temperature at which, due to imminent danger, emergency measures must be initiated.

| SADT 1 | Control temperatures | Emergency temperature |

|---|---|---|

| SADT ≤20°C (68°F) | 20°C (36°F) below SADT | 10°C (18°F) below SADT. |

| 20°C (68°F) <SADT ≤35°C (95°F) | 15°C (27°F) below SADT | 10°C (18°F) below SADT. |

| 35°C (95°F) <SADT ≤50°C (122°F) | 10°C (18°F) below SADT | 5°C (9°F) below SADT. |

| 50°C (122°F) <SADT | (2) | (2) |

| 1 Self-accelerating decomposition temperature. | ||

| 2 Temperature control not required. | ||

(2) For self-reactive materials listed in §173.224(b) Table control and emergency temperatures, where required are shown in Columns 5 and 6, respectively. For organic peroxides listed in The Organic Peroxides Table in §173.225 control and emergency temperatures, where required, are shown in Columns 7a and 7b, respectively.

* * * * *

§173.27 General requirements for transportation by aircraft.

* * * * *

(f) * * *

(2) * * *

(i) * * *

(D) Divisions 4.1 (self-reactive), 4.2 (spontaneously combustible) (primary or subsidiary risk), and 4.3 (dangerous when wet) (liquids);

* * * * *

§173.124 Class 4, Divisions 4.1, 4.2 and 4.3— Definitions.

(a) * * *

(4) * * *

(iv) The provisions concerning polymerizing substances in paragraph (a)(4) will be effective until January 2, 2023.

* * * * *

§173.137 Class 8—Assignment of packing group.

The packing group of a Class 8 material is indicated in Column 5 of the §172.101 Table. When the §172.101 Table provides more than one packing group for a Class 8 material, the packing group must be determined using data obtained from tests conducted in accordance with the OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Test No. 435, “ In Vitro Membrane Barrier Test Method for Skin Corrosion” (IBR, see §171.7 of this subchapter) or Test No. 404, “Acute Dermal Irritation/Corrosion” (IBR, see §171.7 of this subchapter). A material that is determined not to be corrosive in accordance with OECD Guideline for the Testing of Chemicals, Test No. 430, “ In Vitro Skin Corrosion: Transcutaneous Electrical Resistance Test (TER)” (IBR, see §171.7 of this subchapter) or Test No. 431, “ In Vitro Skin Corrosion: Reconstructed Human Epidermis (RHE) Test Method” (IBR, see §171.7 of this subchapter) may be considered not to be corrosive to human skin for the purposes of this subchapter without further testing. However, a material determined to be corrosive in accordance with Test No. 430 must be further tested using Test No. 435 or Test No. 404. If the in vitro test results indicate that the substance or mixture is corrosive, but the test method does not clearly distinguish between assignment of packing groups II and III, the material may be considered to be in packing group II without further testing. The packing group assignment using data obtained from tests conducted in accordance with OECD Guideline Test No. 404 or Test No. 435 must be as follows:

* * * * *

§173.151 Exceptions for Class 4.

* * * * *

(d) Limited quantities of Division 4.3. Limited quantities of dangerous when wet solids (Division 4.3) in Packing Groups II and III are excepted from labeling requirements, unless the material is offered for transportation or transported by aircraft, and are excepted from the specification packaging requirements of this subchapter when packaged in combination packagings according to this paragraph. For transportation by aircraft, the package must also conform to applicable requirements of §173.27 of this part (e.g., authorized materials, inner packaging quantity limits and closure securement) and only hazardous material authorized aboard passenger-carrying aircraft may be transported as a limited quantity. A limited quantity package that conforms to the provisions of this section is not subject to the shipping paper requirements of subpart C of part 172 of this subchapter, unless the material meets the definition of a hazardous substance, hazardous waste, marine pollutant, or is offered for transportation and transported by aircraft or vessel. In addition, shipments of limited quantities are not subject to subpart F (Placarding) of part 172 of this subchapter. Each package must conform to the packaging requirements of subpart B of this part and may not exceed 30 kg (66 pounds) gross weight. Except for transportation by aircraft, the following combination packagings are authorized:

* * * * *

§173.167 Consumer commodities.

(a) Effective January 1, 2013, a “consumer commodity” (see §171.8 of this subchapter) when offered for transportation by aircraft may only include articles or substances of Class 2 (non-toxic aerosols only), Class 3 (Packing Group II and III only), Division 6.1 (Packing Group III only), UN3077, UN3082, UN3175, UN3334, and UN3335, provided such materials do not have a subsidiary risk and are authorized aboard a passenger-carrying aircraft. Consumer commodities are excepted from the specification outer packaging requirements of this subchapter. Packages prepared under the requirements of this section are excepted from labeling and shipping papers when transported by highway or rail. Except as indicated in §173.24(i), each completed package must conform to §§173.24 and 173.24a of this subchapter. Additionally, except for the pressure differential requirements in §173.27(c), the requirements of §173.27 do not apply to packages prepared in accordance with this section. Packages prepared under the requirements of this section may be offered for transportation and transported by all modes. As applicable, the following apply:

(1) Inner and outer packaging quantity limits. (i) Non-toxic aerosols, as defined in §171.8 of this subchapter and constructed in accordance with §173.306 of this part, in non-refillable, non-metal containers not exceeding 120 mL (4 fluid ounces) each, or in non-refillable metal containers not exceeding 820 mL (28 ounces) each, except that flammable aerosols may not exceed 500 mL (16.9 ounces) each;

(ii) Liquids, in inner packagings not exceeding 500 mL (16.9 ounces) each. Liquids must not completely fill an inner packaging at 55°C;

(iii) Solids, in inner packagings not exceeding 500 g (1.0 pounds) each; or

(iv) Any combination thereof not to exceed 30 kg (66 pounds) gross weight as prepared for shipment.

(2) Closures. Friction-type closures must be secured by positive means. The body and closure of any packaging must be constructed so as to be able to adequately resist the effects of temperature and vibration occurring in conditions normally incident to air transportation. The closure device must be so designed that it is unlikely that it can be incorrectly or incompletely closed.

(3) Absorbent material. Inner packagings must be tightly packaged in strong outer packagings. Absorbent and cushioning material must not react dangerously with the contents of inner packagings. Glass or earthenware inner packagings containing liquids of Class 3 or Division 6.1, sufficient absorbent material must be provided to absorb the entire contents of the largest inner packaging contained in the outer packaging. Absorbent material is not required if the glass or earthenware inner packagings are sufficiently protected as packaged for transport that it is unlikely a failure would occur and, if a failure did occur, that it would be unlikely that the contents would leak from the outer packaging.

(4) Drop test capability. Breakable inner packagings (e.g., glass, earthenware, or brittle plastic) must be packaged to prevent failure under conditions normally incident to transport. Packages of consumer commodities as prepared for transport must be capable of withstanding a 1.2 m drop on solid concrete in the position most likely to cause damage. In order to pass the test, the outer packaging must not exhibit any damage liable to affect safety during transport and there must be no leakage from the inner packaging(s).

(5) Stack test capability. Packages of consumer commodities must be capable of withstanding, without failure or leakage of any inner packaging and without any significant reduction in effectiveness, a force applied to the top surface for a duration of 24 hours equivalent to the total weight of identical packages if stacked to a height of 3.0 m (including the test sample).

(b) When offered for transportation by aircraft:

(1) Packages prepared under the requirements of this section are to be marked as a limited quantity in accordance with §172.315(b)(1) and labeled as a Class 9 article or substance, as appropriate, in accordance with subpart E of part 172 of this subchapter; and

(2) Pressure differential capability: Except for UN3082, inner packagings intended to contain liquids must be capable of meeting the pressure differential requirements (75 kPa) prescribed in §173.27(c) of this part. The capability of a packaging to withstand an internal pressure without leakage that produces the specified pressure differential should be determined by successfully testing design samples or prototypes.

§173.185 Lithium cells and batteries.

* * * * *

(a) * * *

(3) Beginning January 1, 2022 each manufacturer and subsequent distributor of lithium cells or batteries manufactured on or after January 1, 2008, must make available a test summary. The test summary must include the following elements:

* * * * *

* * * * *

(ix) Reference to the revised edition of the UN Manual of Tests and Criteria used and to amendments thereto, if any; and

* * * * *

(b) * * *

(3) * * *

(iii) * * *

(A) Be placed in inner packagings that completely enclose the cell or battery, then placed in an outer packaging. The completed package for the cells or batteries must meet the Packing Group II performance requirements as specified in paragraph (b)(3)(ii) of this section; or

(B) Be placed in inner packagings that completely enclose the cell or battery, then placed with equipment in a package that meets the Packing Group II performance requirements as specified in paragraph (b)(3)(ii) of this section.

* * * * *

(4) * * *

(ii) Equipment must be secured to prevent damage caused by shifting within the outer packaging and be packed so as to prevent accidental operation during transport; and

(iii) Any spare lithium cells or batteries packed with the equipment must be packaged in accordance with paragraph (b)(3) of this section.

* * * * *

(5) Lithium batteries that weigh 12 kg (26.5 pounds) or more and have a strong, impact-resistant outer casing may be packed in strong outer packagings; in protective enclosures (for example, in fully enclosed or wooden slatted crates); or on pallets or other handling devices, instead of packages meeting the UN performance packaging requirements in paragraphs (b)(3)(ii) and (iii) of this section. Batteries must be secured to prevent inadvertent shifting, and the terminals may not support the weight of other superimposed elements. Batteries packaged in accordance with this paragraph may be transported by cargo aircraft if approved by the Associate Administrator.

* * * * *

(c) * * *

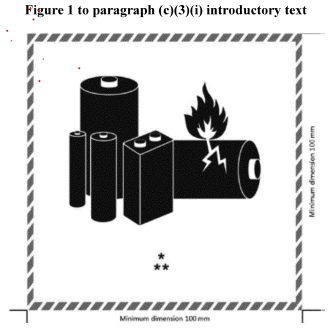

(3) Lithium battery mark. Each package must display the lithium battery mark except when a package contains only button cell batteries contained in equipment (including circuit boards), or when a consignment contains two packages or fewer where each package contains not more than four lithium cells or two lithium batteries contained in equipment. [Change Notice][Previous Text]

(i) The mark must indicate the UN number: “UN3090” for lithium metal cells or batteries; or “UN3480” for lithium ion cells or batteries. Where the lithium cells or batteries are contained in, or packed with, equipment, the UN number “UN3091” or “UN3481,” as appropriate, must be indicated. Where a package contains lithium cells or batteries assigned to different UN numbers, all applicable UN numbers must be indicated on one or more marks. The package must be of such size that there is adequate space to affix the mark on one side without the mark being folded.

(A) The mark must be in the form of a rectangle or a square with hatched edging. The mark must be not less than 100 mm (3.9 inches) wide by 100 mm (3.9 inches) high and the minimum width of the hatching must be 5 mm (0.2 inches), except marks of 100 mm (3.9 inches) wide by 70 mm (2.8 inches) high may be used on a package containing lithium batteries when the package is too small for the larger mark;

(B) The symbols and letters must be black on white or suitable contrasting background and the hatching must be red;

(C) The “*” must be replaced by the appropriate UN number(s) and the “**” must be replaced by a telephone number for additional information; and

(D) Where dimensions are not specified, all features shall be in approximate proportion to those shown.

(ii) [Reserved]

(iii) When packages are placed in an overpack, the lithium battery mark shall either be clearly visible through the overpack or be reproduced on the outside of the overpack and the overpack shall be marked with the word “OVERPACK”. The lettering of the “OVERPACK” mark shall be at least 12 mm (0.47 inches) high.

(4) Air transportation. (i) For transportation by aircraft, lithium cells and batteries may not exceed the limits in the following Table 1 to paragraph (c)(4)(i). The limits on the maximum number of batteries and maximum net quantity of batteries in the following table may not be combined in the same package. The limits in the following table do not apply to lithium cells and batteries packed with, or contained in, equipment.

| Contents | Lithium metal cells and/or batteries with a lithium content not more than 0.3 g | Lithium metal cells with a lithium content more than 0.3 g but not more than 1 g | Lithium metal batteries with a lithium content more than 0.3 g but not more than 2 g | Lithium ion cells and/or batteries with a watt-hour rating not more than 2.7 Wh | Lithium ion cells with a watt-hour rating more than 2.7 Wh but not more than 20 Wh | Lithium ion batteries with a watt-hour rating more than 2.7 Wh but not more than 100 Wh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum number of cells/batteries per package | No Limit | 8 cells | 2 batteries | No Limit | 8 cells | 2 batteries. |

| Maximum net quantity (mass) per package | 2.5 kg | n/a | n/a | 2.5 kg | n/a | n/a. |

(ii) Not more than one package prepared in accordance with paragraph (c)(4)(i) of this section may be placed into an overpack.

(iii) A shipper is not permitted to offer for transport more than one package prepared in accordance with the provisions of paragraph (c)(4)(i) of this section in any single consignment.

(iv) Each shipment with packages required to display the paragraph (c)(3)(i) lithium battery mark must include an indication on the air waybill of compliance with this paragraph (c)(4) (or the applicable ICAO Technical Instructions Packing Instruction), when an air waybill is used.

(v) Packages and overpacks of lithium batteries prepared in accordance with paragraph (c)(4)(i) of this section must be offered to the operator separately from cargo which is not subject to the requirements of this subchapter and must not be loaded into a unit load device before being offered to the operator.

(vi) For lithium batteries packed with, or contained in, equipment, the number of batteries in each package is limited to the minimum number required to power the piece of equipment, plus two spare sets, and the total net quantity (mass) of the lithium cells or batteries in the completed package must not exceed 5 kg. A “set” of cells or batteries is the number of individual cells or batteries that are required to power each piece of equipment.

(vii) Each person who prepares a package for transport containing lithium cells or batteries, including cells or batteries packed with, or contained in, equipment in accordance with the conditions and limitations of this paragraph (c)(4), must receive instruction on these conditions and limitations, corresponding to their functions.

(viii) Lithium cells and batteries must not be packed in the same outer packaging with other hazardous materials. Packages prepared in accordance with paragraph (c)(4)(i) of this section must not be placed into an overpack with packages containing hazardous materials and articles of Class 1 (explosives) other than Division 1.4S, Division 2.1 (flammable gases), Class 3 (flammable liquids), Division 4.1 (flammable solids), or Division 5.1 (oxidizers).

(5) For transportation by aircraft, a package that exceeds the number or quantity (mass) limits in the table shown in paragraph (c)(4)(i) of this section, the overpack limit described in paragraph (c)(4)(ii) of this section, or the consignment limit described in paragraph (c)(4)(iii) of this section is subject to all applicable requirements of this subchapter, except that a package containing no more than 2.5 kg lithium metal cells or batteries or 10 kg lithium ion cells or batteries is not subject to the UN performance packaging requirements in paragraph (b)(3)(ii) of this section when the package displays both the lithium battery mark in paragraph (c)(3)(i) and the Class 9 Lithium Battery label specified in §172.447 of this subchapter. This paragraph does not apply to batteries or cells packed with or contained in equipment.

* * * * *

(e) * * *

(5) Lithium batteries, including lithium batteries contained in equipment, that weigh 12 kg (26.5 pounds) or more and have a strong, impact-resistant outer casing may be packed in strong outer packagings, in protective enclosures (for example, in fully enclosed or wooden slatted crates), or on pallets or other handling devices, instead of packages meeting the UN performance packaging requirements in paragraphs (b)(3)(ii) and (iii) of this section. The battery must be secured to prevent inadvertent shifting, and the terminals may not support the weight of other superimposed elements;

(6) Irrespective of the limit specified in column (9B) of the §172.101 Hazardous Materials Table, the battery or battery assembly prepared for transport in accordance with this paragraph may have a mass exceeding 35 kg gross weight when transported by cargo aircraft;

(7) Batteries or battery assemblies packaged in accordance with this paragraph are not permitted for transportation by passenger-carrying aircraft, and may be transported by cargo aircraft only if approved by the Associate Administrator prior to transportation; and

* * * * *

§173.224 Packaging and control and emergency temperatures for self-reactive materials.

* * * * *

(b) * * *

(4) Packing method. Column 4 specifies the highest packing method which is authorized for the self-reactive material. A packing method corresponding to a smaller package size may be used, but a packing method corresponding to a larger package size may not be used. The Table of Packing Methods in §173.225(d) defines the packing methods. Bulk packagings for Type F self-reactive substances are authorized by §173.225(f) for IBCs and §173.225(h) for bulk packagings other than IBCs. The formulations listed in §173.225(f) for IBCs and in §173.225(g) for portable tanks may also be transported packed in accordance with packing method OP8, with the same control and emergency temperatures, if applicable. Additional bulk packagings are authorized if approved by the Associate Administrator.

* * * * *

|

Self-reactive substance

(1) |

Identification No.

(2) |

Concentra-

tion—(%) (3) |

Packing method

(4) |

Control

tempera- ture— (°C) (5) |

Emer-

gency tempera- ture— (6) |

Notes

(7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notes: | ||||||

| 1. The emergency and control temperatures must be determined in accordance with §173.21(f). | ||||||

| 2. With a compatible diluent having a boiling point of not less than 150 °C. | ||||||

| 3. Samples may only be offered for transportation under the provisions of paragraph (c)(3) of this section. | ||||||

| 4. This entry applies to mixtures of esters of 2-diazo-1-naphthol-4-sulphonic acid and 2-diazo-1-naphthol-5-sulphonic acid. | ||||||

| 5. This entry applies to the technical mixture in n-butanol within the specified concentration limits of the (Z) isomer. | ||||||

| Acetone-pyrogallol copolymer 2-diazo-1-naphthol-5-sulphonate | 3228 | 100 | OP8 | |||

| Azodicarbonamide formulation type B, temperature controlled | 3232 | <100 | OP5 | 1 | ||

| Azodicarbonamide formulation type C | 3224 | <100 | OP6 | |||

| Azodicarbonamide formulation type C, temperature controlled | 3234 | <100 | OP6 | 1 | ||

| Azodicarbonamide formulation type D | 3226 | <100 | OP7 | |||

| Azodicarbonamide formulation type D, temperature controlled | 3236 | <100 | OP7 | 1 | ||

| 2,2′-Azodi(2,4-dimethyl-4-methoxyvaleronitrile) | 3236 | 100 | OP7 | −5 | +5 | |

| 2,2′-Azodi(2,4-dimethylvaleronitrile) | 3236 | 100 | OP7 | +10 | +15 | |

| 2,2′-Azodi(ethyl 2-methylpropionate) | 3235 | 100 | OP7 | +20 | +25 | |

| 1,1-Azodi(hexahydrobenzonitrile) | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| 2,2-Azodi(isobutyronitrile) | 3234 | 100 | OP6 | +40 | +45 | |

| 2,2′-Azodi(isobutyronitrile) as a water based paste | 3224 | ≤50 | OP6 | |||

| 2,2-Azodi(2-methylbutyronitrile) | 3236 | 100 | OP7 | +35 | +40 | |

| Benzene-1,3-disulphonylhydrazide, as a paste | 3226 | 52 | OP7 | |||

| Benzene sulphohydrazide | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| 4-(Benzyl(ethyl)amino)-3-ethoxybenzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| 4-(Benzyl(methyl)amino)-3-ethoxybenzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 100 | OP7 | +40 | +45 | |

| 3-Chloro-4-diethylaminobenzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| 2-Diazo-1-Naphthol sulphonic acid ester mixture | 3226 | <100 | OP7 | 4 | ||

| 2-Diazo-1-Naphthol-4-sulphonyl chloride | 3222 | 100 | OP5 | |||

| 2-Diazo-1-Naphthol-5-sulphonyl chloride | 3222 | 100 | OP5 | |||

| 2,5-Dibutoxy-4-(4-morpholinyl)-Benzenediazonium, tetrachlorozincate (2:1) | 3228 | 100 | OP8 | |||

| 2,5-Diethoxy-4-morpholinobenzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 67−100 | OP7 | +35 | +40 | |

| 2,5-Diethoxy-4-morpholinobenzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 66 | OP7 | +40 | +45 | |

| 2,5-Diethoxy-4-morpholinobenzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate | 3236 | 100 | OP7 | +30 | +35 | |

| 2,5-Diethoxy-4-(phenylsulphonyl)benzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 67 | OP7 | +40 | +45 | |

| 2,5-Diethoxy-4-(4-morpholinyl)-benzenediazonium sulphate | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| Diethylene glycol bis(allyl carbonate) + Diisopropylperoxydicarbonate | 3237 | ≥88 + ≤12 | OP8 | −10 | 0 | |

| 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-(4-methylphenylsulphony)benzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 79 | OP7 | +40 | +45 | |

| 4-Dimethylamino-6-(2-dimethylaminoethoxy)toluene-2-diazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 100 | OP7 | +40 | +45 | |

| 4-(Dimethylamino)-benzenediazonium trichlorozincate (-1) | 3228 | 100 | OP8 | |||

| N,N′-Dinitroso-N, N′-dimethyl-terephthalamide, as a paste | 3224 | 72 | OP6 | |||

| N,N′-Dinitrosopentamethylenetetramine | 3224 | 82 | OP6 | 2 | ||

| Diphenyloxide-4,4′-disulphohydrazide | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| Diphenyloxide-4,4′-disulphonylhydrazide | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| 4-Dipropylaminobenzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| 2-(N,N-Ethoxycarbonylphenylamino)-3-methoxy-4-(N-methyl-N- cyclohexylamino)benzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 63−92 | OP7 | +40 | +45 | |

| 2-(N,N-Ethoxycarbonylphenylamino)-3-methoxy-4-(N-methyl-N- cyclohexylamino)benzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 62 | OP7 | +35 | +40 | |

| N-Formyl-2-(nitromethylene)-1,3-perhydrothiazine | 3236 | 100 | OP7 | +45 | +50 | |

| 2-(2-Hydroxyethoxy)-1-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)benzene-4-diazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 100 | OP7 | +45 | +50 | |

| 3-(2-Hydroxyethoxy)-4-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)benzenediazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 100 | OP7 | +40 | +45 | |

| 2-(N,N-Methylaminoethylcarbonyl)-4-(3,4-dimethyl-phenylsulphonyl)benzene diazonium zinc chloride | 3236 | 96 | OP7 | +45 | +50 | |

| 4-Methylbenzenesulphonylhydrazide | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| 3-Methyl-4-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)benzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate | 3234 | 95 | OP6 | +45 | +50 | |

| 4-Nitrosophenol | 3236 | 100 | OP7 | +35 | +40 | |

| Phosphorothioic acid, O-[(cyanophenyl methylene) azanyl] O,O-diethyl ester | 3227 | 82−91 (Z isomer) | OP8 | 5 | ||

| Self-reactive liquid, sample | 3223 | OP2 | 3 | |||

| Self-reactive liquid, sample, temperature control | 3233 | OP2 | 3 | |||

| Self-reactive solid, sample | 3224 | OP2 | 3 | |||

| Self-reactive solid, sample, temperature control | 3234 | OP2 | 3 | |||

| Sodium 2-diazo-1-naphthol-4-sulphonate | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| Sodium 2-diazo-1-naphthol-5-sulphonate | 3226 | 100 | OP7 | |||

| Tetramine palladium (II) nitrate | 3234 | 100 | OP6 | +30 | +35 | |

§173.225 Packaging requirements and other provisions for organic peroxides.

* * * * *

(c) * * *

| Technical name | ID No. | Concentration (mass %) | Diluent (mass %) | Water (mass %) | Packing method | Temperature (°C) | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | I | Control | Emergency | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4a) | (4b) | (4c) | (5) | (6) | (7a) | (7b) | (8) |

| Acetyl acetone peroxide | UN3105 | ≤42 | ≥48 | ≥8 | OP7 | 2 | ||||

| Acetyl acetone peroxide [as a paste] | UN3106 | ≤32 | OP7 | 21 | ||||||

| Acetyl cyclohexanesulfonyl peroxide | UN3112 | ≤82 | ≥12 | OP4 | −10 | 0 | ||||

| Acetyl cyclohexanesulfonyl peroxide | UN3115 | ≤32 | ≥68 | OP7 | −10 | 0 | ||||

| tert-Amyl hydroperoxide | UN3107 | ≤88 | ≥6 | ≥6 | OP8 | |||||

| tert-Amyl peroxyacetate | UN3105 | ≤62 | ≥38 | OP7 | ||||||

| tert-Amyl peroxybenzoate | UN3103 | ≤100 | OP5 | |||||||

| tert-Amyl peroxy-2-ethylhexanoate | UN3115 | ≤100 | OP7 | +20 | +25 | |||||

| tert-Amyl peroxy-2-ethylhexyl carbonate | UN3105 | ≤100 | OP7 | |||||||

| tert-Amyl peroxy isopropyl carbonate | UN3103 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP5 | ||||||

| tert-Amyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3115 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| tert-Amyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3119 | ≤47 | ≥53 | OP8 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| tert-Amyl peroxypivalate | UN3113 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP5 | +10 | +15 | ||||

| tert-Amyl peroxypivalate | UN3119 | ≤32 | ≥68 | OP8 | +10 | +15 | ||||

| tert-Amyl peroxy-3,5,5-trimethylhexanoate | UN3105 | ≤100 | OP7 | |||||||

| tert-Butyl cumyl peroxide | UN3109 | >42−100 | OP8 | 9 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl cumyl peroxide | UN3108 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP8 | 9 | |||||

| n-Butyl-4,4-di-(tert-butylperoxy)valerate | UN3103 | >52−100 | OP5 | |||||||

| n-Butyl-4,4-di-(tert-butylperoxy)valerate | UN3108 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP8 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl hydroperoxide | UN3103 | >79−90 | ≥10 | OP5 | 13 | |||||

| tert-Butyl hydroperoxide | UN3105 | ≤80 | ≥20 | OP7 | 4, 13 | |||||

| tert-Butyl hydroperoxide | UN3107 | ≤79 | >14 | OP8 | 13, 16 | |||||

| tert-Butyl hydroperoxide | UN3109 | ≤72 | ≥28 | OP8 | 13 | |||||

| tert-Butyl hydroperoxide [and] Di-tert-butylperoxide | UN3103 | <82 + >9 | ≥7 | OP5 | 13 | |||||

| tert-Butyl monoperoxymaleate | UN3102 | >52−100 | OP5 | |||||||

| tert-Butyl monoperoxymaleate | UN3103 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP6 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl monoperoxymaleate | UN3108 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP8 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl monoperoxymaleate [as a paste] | UN3108 | ≤52 | OP8 | |||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyacetate | UN3101 | >52−77 | ≥23 | OP5 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyacetate | UN3103 | >32−52 | ≥48 | OP6 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyacetate | UN3109 | ≤32 | ≥68 | OP8 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxybenzoate | UN3103 | >77−100 | OP5 | |||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxybenzoate | UN3105 | >52−77 | ≥23 | OP7 | 1 | |||||

| tert-Butyl peroxybenzoate | UN3106 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxybenzoate | UN3109 | ≤32 | ≥68 | OP8 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxybutyl fumarate | UN3105 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxycrotonate | UN3105 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxydiethylacetate | UN3113 | ≤100 | OP5 | +20 | +25 | |||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-2-ethylhexanoate | UN3113 | >52−100 | OP6 | +20 | +25 | |||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-2-ethylhexanoate | UN3117 | >32−52 | ≥48 | OP8 | +30 | +35 | ||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-2-ethylhexanoate | UN3118 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP8 | +20 | +25 | ||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-2-ethylhexanoate | UN3119 | ≤32 | ≥68 | OP8 | +40 | +45 | ||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-2-ethylhexanoate [and] 2,2-di-(tert-Butylperoxy)butane | UN3106 | ≤12 + ≤14 | ≥14 | ≥60 | OP7 | |||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-2-ethylhexanoate [and] 2,2-di-(tert-Butylperoxy)butane | UN3115 | ≤31 + ≤36 | ≥33 | OP7 | +35 | +40 | ||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-2-ethylhexylcarbonate | UN3105 | ≤100 | OP7 | |||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyisobutyrate | UN3111 | >52−77 | ≥23 | OP5 | +15 | +20 | ||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyisobutyrate | UN3115 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | +15 | +20 | ||||

| tert-Butylperoxy isopropylcarbonate | UN3103 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP5 | ||||||

| 1-(2-tert-Butylperoxy isopropyl)-3-isopropenylbenzene | UN3105 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | ||||||

| 1-(2-tert-Butylperoxy isopropyl)-3-isopropenylbenzene | UN3108 | ≤42 | ≥58 | OP8 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-2-methylbenzoate | UN3103 | ≤100 | OP5 | |||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3115 | >77−100 | OP7 | −5 | +5 | |||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3115 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyneodecanoate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤52 | OP8 | 0 | +10 | |||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyneodecanoate [as a stable dispersion in water (frozen)] | UN3118 | ≤42 | OP8 | 0 | +10 | |||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3119 | ≤32 | ≥68 | OP8 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyneoheptanoate | UN3115 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| tert-Butyl peroxyneoheptanoate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3117 | ≤42 | OP8 | 0 | +10 | |||||

| tert-Butyl peroxypivalate | UN3113 | >67−77 | ≥23 | OP5 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| tert-Butyl peroxypivalate | UN3115 | >27−67 | ≥33 | OP7 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| tert-Butyl peroxypivalate | UN3119 | ≤27 | ≥73 | OP8 | +30 | +35 | ||||

| tert-Butylperoxy stearylcarbonate | UN3106 | ≤100 | OP7 | |||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-3,5,5-trimethylhexanoate | UN3105 | >37−100 | OP7 | |||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-3,5,5-trimethlyhexanoate | UN3106 | ≤42 | ≥58 | OP7 | ||||||

| tert-Butyl peroxy-3,5,5-trimethylhexanoate | UN3109 | ≤37 | ≥63 | OP8 | ||||||

| 3-Chloroperoxybenzoic acid | UN3102 | >57−86 | ≥14 | OP1 | ||||||

| 3-Chloroperoxybenzoic acid | UN3106 | ≤57 | ≥3 | ≥40 | OP7 | |||||

| 3-Chloroperoxybenzoic acid | UN3106 | ≤77 | ≥6 | ≥17 | OP7 | |||||

| Cumyl hydroperoxide | UN3107 | >90−98 | ≤10 | OP8 | 13 | |||||

| Cumyl hydroperoxide | UN3109 | ≤90 | ≥10 | OP8 | 13, 15 | |||||

| Cumyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3115 | ≤87 | ≥13 | OP7 | −10 | 0 | ||||

| Cumyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3115 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | −10 | 0 | ||||

| Cumyl peroxyneodecanoate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤52 | OP8 | −10 | 0 | |||||

| Cumyl peroxyneoheptanoate | UN3115 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | −10 | 0 | ||||

| Cumyl peroxypivalate | UN3115 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | −5 | +5 | ||||

| Cyclohexanone peroxide(s) | UN3104 | ≤91 | ≥9 | OP6 | 13 | |||||

| Cyclohexanone peroxide(s) | UN3105 | ≤72 | ≥28 | OP7 | 5 | |||||

| Cyclohexanone peroxide(s) [as a paste] | UN3106 | ≤72 | OP7 | 5, 21 | ||||||

| Cyclohexanone peroxide(s) | Exempt | ≤32 | >68 | Exempt | 29 | |||||

| Diacetone alcohol peroxides | UN3115 | ≤57 | ≥26 | ≥8 | OP7 | +40 | +45 | 5 | ||

| Diacetyl peroxide | UN3115 | ≤27 | ≥73 | OP7 | +20 | +25 | 8,13 | |||

| Di-tert-amyl peroxide | UN3107 | ≤100 | OP8 | |||||||

| ([3R- (3R, 5aS, 6S, 8aS, 9R, 10R, 12S, 12aR**)]-Decahydro-10-methoxy-3, 6, 9-trimethyl-3, 12-epoxy-12H-pyrano [4, 3- j]-1, 2-benzodioxepin) | UN3106 | ≤100 | OP7 | |||||||

| 2,2-Di-(tert-amylperoxy)-butane | UN3105 | ≤57 | ≥43 | OP7 | ||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-amylperoxy)cyclohexane | UN3103 | ≤82 | ≥18 | OP6 | ||||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide | UN3102 | >52−100 | ≤48 | OP2 | 3 | |||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide | UN3102 | >77−94 | ≥6 | OP4 | 3 | |||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide | UN3104 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP6 | ||||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide | UN3106 | ≤62 | ≥28 | ≥10 | OP7 | |||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide [as a paste] | UN3106 | >52−62 | OP7 | 21 | ||||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide | UN3106 | >35−52 | ≥48 | OP7 | ||||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide | UN3107 | >36−42 | ≥18 | ≤40 | OP8 | |||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide [as a paste] | UN3108 | ≤56.5 | ≥15 | OP8 | ||||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide [as a paste] | UN3108 | ≤52 | OP8 | 21 | ||||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3109 | ≤42 | OP8 | |||||||

| Dibenzoyl peroxide | Exempt | ≤35 | ≥65 | Exempt | 29 | |||||

| Di-(4-tert-butylcyclohexyl)peroxydicarbonate | UN3114 | ≤100 | OP6 | +30 | +35 | |||||

| Di-(4-tert-butylcyclohexyl)peroxydicarbonate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤42 | OP8 | +30 | +35 | |||||

| Di-(4-tert-butylcyclohexyl)peroxydicarbonate [as a paste] | UN3116 | ≤42 | OP7 | +35 | +40 | |||||

| Di-tert-butyl peroxide | UN3107 | >52−100 | OP8 | |||||||

| Di-tert-butyl peroxide | UN3109 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP8 | 24 | |||||

| Di-tert-butyl peroxyazelate | UN3105 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | ||||||

| 2,2-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)butane | UN3103 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP6 | ||||||

| 1,6-Di-(tert-butylperoxycarbonyloxy)hexane | UN3103 | ≤72 | ≥28 | OP5 | ||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexane | UN3101 | >80−100 | OP5 | |||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexane | UN3103 | >52−80 | ≥20 | OP5 | ||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)-cyclohexane | UN3103 | ≤72 | ≥28 | OP5 | 30 | |||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexane | UN3105 | >42−52 | ≥48 | OP7 | ||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexane | UN3106 | ≤42 | ≥13 | ≥45 | OP7 | |||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexane | UN3107 | ≤27 | ≥25 | OP8 | 22 | |||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexane | UN3109 | ≤42 | ≥58 | OP8 | ||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-Butylperoxy) cyclohexane | UN3109 | ≤37 | ≥63 | OP8 | ||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexane | UN3109 | ≤25 | ≥25 | ≥50 | OP8 | |||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexane | UN3109 | ≤13 | ≥13 | ≥74 | OP8 | |||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexane + tert-Butyl peroxy-2-ethylhexanoate | UN3105 | ≤43 + ≤16 | ≥41 | OP7 | ||||||

| Di-n-butyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3115 | >27−52 | ≥48 | OP7 | −15 | −5 | ||||

| Di-n-butyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3117 | ≤27 | ≥73 | OP8 | −10 | 0 | ||||

| Di-n-butyl peroxydicarbonate [as a stable dispersion in water (frozen)] | UN3118 | ≤42 | OP8 | −15 | −5 | |||||

| Di-sec-butyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3113 | >52−100 | OP4 | −20 | −10 | 6 | ||||

| Di-sec-butyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3115 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | −15 | −5 | ||||

| Di-(tert-butylperoxyisopropyl) benzene(s) | UN3106 | >42−100 | ≤57 | OP7 | 1, 9 | |||||

| Di-(tert-butylperoxyisopropyl) benzene(s) | Exempt | ≤42 | ≥58 | Exempt | ||||||

| Di-(tert-butylperoxy)phthalate | UN3105 | >42−52 | ≥48 | OP7 | ||||||

| Di-(tert-butylperoxy)phthalate [as a paste] | UN3106 | ≤52 | OP7 | 21 | ||||||

| Di-(tert-butylperoxy)phthalate | UN3107 | ≤42 | ≥58 | OP8 | ||||||

| 2,2-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)propane | UN3105 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | ||||||

| 2,2-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)propane | UN3106 | ≤42 | ≥13 | ≥45 | OP7 | |||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)-3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexane | UN3101 | >90−100 | OP5 | |||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)-3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexane | UN3103 | >57−90 | ≥10 | OP5 | ||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)-3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexane | UN3103 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP5 | ||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)-3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexane | UN3103 | ≤90 | ≥10 | OP5 | 30 | |||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)-3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexane | UN3110 | ≤57 | ≥43 | OP8 | ||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)-3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexane | UN3107 | ≤57 | ≥43 | OP8 | ||||||

| 1,1-Di-(tert-butylperoxy)-3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexane | UN3107 | ≤32 | ≥26 | ≥42 | OP8 | |||||

| Dicetyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3120 | ≤100 | OP8 | +30 | +35 | |||||

| Dicetyl peroxydicarbonate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤42 | OP8 | +30 | +35 | |||||

| Di-4-chlorobenzoyl peroxide | UN3102 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP5 | ||||||

| Di-4-chlorobenzoyl peroxide | Exempt | ≤32 | ≥68 | Exempt | 29 | |||||

| Di-2,4-dichlorobenzoyl peroxide [as a paste] | UN3118 | ≤52 | OP8 | +20 | +25 | |||||

| Di-4-chlorobenzoyl peroxide [as a paste] | UN3106 | ≤52 | OP7 | 21 | ||||||

| Dicumyl peroxide | UN3110 | >52−100 | ≤48 | OP8 | 9 | |||||

| Dicumyl peroxide | Exempt | ≤52 | ≥48 | Exempt | 29 | |||||

| Dicyclohexyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3112 | >91−100 | OP3 | +10 | +15 | |||||

| Dicyclohexyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3114 | ≤91 | ≥9 | OP5 | +10 | +15 | ||||

| Dicyclohexyl peroxydicarbonate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤42 | OP8 | +15 | +20 | |||||

| Didecanoyl peroxide | UN3114 | ≤100 | OP6 | +30 | +35 | |||||

| 2,2-Di-(4,4-di(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexyl)propane | UN3106 | ≤42 | ≥58 | OP7 | ||||||

| 2,2-Di-(4,4-di(tert-butylperoxy)cyclohexyl)propane | UN3107 | ≤22 | ≥78 | OP8 | ||||||

| Di-2,4-dichlorobenzoyl peroxide | UN3102 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP5 | ||||||

| Di-2,4-dichlorobenzoyl peroxide [as a paste with silicone oil] | UN3106 | ≤52 | OP7 | |||||||

| Di-(2-ethoxyethyl) peroxydicarbonate | UN3115 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | −10 | 0 | ||||

| Di-(2-ethylhexyl) peroxydicarbonate | UN3113 | >77−100 | OP5 | −20 | −10 | |||||

| Di-(2-ethylhexyl) peroxydicarbonate | UN3115 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | −15 | −5 | ||||

| Di-(2-ethylhexyl) peroxydicarbonate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤62 | OP8 | −15 | −5 | |||||

| Di-(2-ethylhexyl) peroxydicarbonate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤52 | OP8 | −15 | −5 | |||||

| Di-(2-ethylhexyl) peroxydicarbonate [as a stable dispersion in water (frozen)] | UN3120 | ≤52 | OP8 | −15 | −5 | |||||

| 2,2-Dihydroperoxypropane | UN3102 | ≤27 | ≥73 | OP5 | ||||||

| Di-(1-hydroxycyclohexyl)peroxide | UN3106 | ≤100 | OP7 | |||||||

| Diisobutyryl peroxide | UN3111 | >32−52 | ≥48 | OP5 | −20 | −10 | ||||

| Diisobutyryl peroxide [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤42 | OP8 | −20 | −10 | |||||

| Diisobutyryl peroxide | UN3115 | ≤32 | ≥68 | OP7 | −20 | −10 | ||||

| Diisopropylbenzene dihydroperoxie | UN3106 | ≤82 | ≥5 | ≥5 | OP7 | 17 | ||||

| Diisopropyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3112 | >52−100 | OP2 | −15 | −5 | |||||

| Diisopropyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3115 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | −20 | −10 | ||||

| Diisopropyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3115 | ≤32 | ≥68 | OP7 | −15 | −5 | ||||

| Dilauroyl peroxide | UN3106 | ≤100 | OP7 | |||||||

| Dilauroyl peroxide [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3109 | ≤42 | OP8 | |||||||

| Di-(3-methoxybutyl) peroxydicarbonate | UN3115 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | −5 | +5 | ||||

| Di-(2-methylbenzoyl)peroxide | UN3112 | ≤87 | ≥13 | OP5 | +30 | +35 | ||||

| Di-(4-methylbenzoyl)peroxide [as a paste with silicone oil] | UN3106 | ≤52 | OP7 | |||||||

| Di-(3-methylbenzoyl) peroxide + Benzoyl (3-methylbenzoyl) peroxide + Dibenzoyl peroxide | UN3115 | ≤20 + ≤18 + ≤4 | ≥58 | OP7 | +35 | +40 | ||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(benzoylperoxy)hexane | UN3102 | >82−100 | OP5 | |||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(benzoylperoxy)hexane | UN3106 | ≤82 | ≥18 | OP7 | ||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(benzoylperoxy)hexane | UN3104 | ≤82 | ≥18 | OP5 | ||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(tert-butylperoxy)hexane | UN3103 | >90−100 | OP5 | |||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(tert-butylperoxy)hexane | UN3105 | >52—90 | ≥10 | OP7 | ||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(tert-butylperoxy)hexane | UN3108 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP8 | ||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(tert-butylperoxy)hexane | UN3109 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP8 | ||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(tert-butylperoxy)hexane [as a paste] | UN3108 | ≤47 | OP8 | |||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(tert-butylperoxy)hexyne-3 | UN3101 | >86−100 | OP5 | |||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(tert-butylperoxy)hexyne-3 | UN3103 | >52−86 | ≥14 | OP5 | ||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(tert-butylperoxy)hexyne-3 | UN3106 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | ||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(2-ethylhexanoylperoxy)hexane | UN3113 | ≤100 | OP5 | +20 | +25 | |||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-dihydroperoxyhexane | UN3104 | ≤82 | ≥18 | OP6 | ||||||

| 2,5-Dimethyl-2,5-di-(3,5,5-trimethylhexanoylperoxy)hexane | UN3105 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | ||||||

| 1,1-Dimethyl-3-hydroxybutylperoxyneoheptanoate | UN3117 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP8 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| Dimyristyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3116 | ≤100 | OP7 | +20 | +25 | |||||

| Dimyristyl peroxydicarbonate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤42 | OP8 | +20 | +25 | |||||

| Di-(2-neodecanoylperoxyisopropyl)benzene | UN3115 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | −10 | 0 | ||||

| Di-(2-neodecanoyl-peroxyisopropyl) benzene, as stable dispersion in water | UN3119 | ≤42 | OP8 | −15 | −5 | |||||

| Di-n-nonanoyl peroxide | UN3116 | ≤100 | OP7 | 0 | +10 | |||||

| Di-n-octanoyl peroxide | UN3114 | ≤100 | OP5 | +10 | +15 | |||||

| Di-(2-phenoxyethyl)peroxydicarbonate | UN3102 | >85−100 | OP5 | |||||||

| Di-(2-phenoxyethyl)peroxydicarbonate | UN3106 | ≤85 | ≥15 | OP7 | ||||||

| Dipropionyl peroxide | UN3117 | ≤27 | ≥73 | OP8 | +15 | +20 | ||||

| Di-n-propyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3113 | ≤100 | OP3 | −25 | −15 | |||||

| Di-n-propyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3113 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP5 | −20 | −10 | ||||

| Disuccinic acid peroxide | UN3102 | >72−100 | OP4 | 18 | ||||||

| Disuccinic acid peroxide | UN3116 | ≤72 | ≥28 | OP7 | +10 | +15 | ||||

| Di-(3,5,5-trimethylhexanoyl) peroxide | UN3115 | >52−82 | ≥18 | OP7 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| Di-(3,5,5-trimethylhexanoyl)peroxide [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤52 | OP8 | +10 | +15 | |||||

| Di-(3,5,5-trimethylhexanoyl) peroxide | UN3119 | >38−52 | ≥48 | OP8 | +10 | +15 | ||||

| Di-(3,5,5-trimethylhexanoyl)peroxide | UN3119 | ≤38 | ≥62 | OP8 | +20 | +25 | ||||

| Ethyl 3,3-di-(tert-amylperoxy)butyrate | UN3105 | ≤67 | ≥33 | OP7 | ||||||

| Ethyl 3,3-di-(tert-butylperoxy)butyrate | UN3103 | >77−100 | OP5 | |||||||

| Ethyl 3,3-di-(tert-butylperoxy)butyrate | UN3105 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | ||||||

| Ethyl 3,3-di-(tert-butylperoxy)butyrate | UN3106 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP7 | ||||||

| 1-(2-ethylhexanoylperoxy)-1,3-Dimethylbutyl peroxypivalate | UN3115 | ≤52 | ≥45 | ≥10 | OP7 | −20 | −10 | |||

| tert-Hexyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3115 | ≤71 | ≥29 | OP7 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| tert-Hexyl peroxypivalate | UN3115 | ≤72 | ≥28 | OP7 | +10 | +15 | ||||

| 3-Hydroxy-1,1-dimethylbutyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3115 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | −5 | +5 | ||||

| 3-Hydroxy-1,1-dimethylbutyl peroxyneodecanoate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤52 | OP8 | −5 | +5 | |||||

| 3-Hydroxy-1,1-dimethylbutyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3117 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP8 | −5 | +5 | ||||

| Isopropyl sec-butyl peroxydicarbonat + Di-sec-butyl peroxydicarbonate + Di-isopropyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3111 | ≤52 + ≤28 + ≤22 | OP5 | −20 | −10 | |||||

| Isopropyl sec-butyl peroxydicarbonate + Di-sec-butyl peroxydicarbonate + Di-isopropyl peroxydicarbonate | UN3115 | ≤32 + ≤15 −18 + ≤12 −15 | ≥38 | OP7 | −20 | −10 | ||||

| Isopropylcumyl hydroperoxide | UN3109 | ≤72 | ≥28 | OP8 | 13 | |||||

| p-Menthyl hydroperoxide | UN3105 | >72−100 | OP7 | 13 | ||||||

| p-Menthyl hydroperoxide | UN3109 | ≤72 | ≥28 | OP8 | ||||||

| Methylcyclohexanone peroxide(s) | UN3115 | ≤67 | ≥33 | OP7 | +35 | +40 | ||||

| Methyl ethyl ketone peroxide(s) | UN3101 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP5 | 5, 13 | |||||

| Methyl ethyl ketone peroxide(s) | UN3105 | ≤45 | ≥55 | OP7 | 5 | |||||

| Methyl ethyl ketone peroxide(s) | UN3107 | ≤40 | ≥60 | OP8 | 7 | |||||

| Methyl isobutyl ketone peroxide(s) | UN3105 | ≤62 | ≥19 | OP7 | 5, 23 | |||||

| Methyl isopropyl ketone peroxide(s) | UN3109 | (See remark 31) | ≥70 | OP8 | 31 | |||||

| Organic peroxide, liquid, sample | UN3103 | OP2 | 12 | |||||||

| Organic peroxide, liquid, sample, temperature controlled | UN3113 | OP2 | 12 | |||||||

| Organic peroxide, solid, sample | UN3104 | OP2 | 12 | |||||||

| Organic peroxide, solid, sample, temperature controlled | UN3114 | OP2 | 12 | |||||||

| 3,3,5,7,7-Pentamethyl-1,2,4-Trioxepane | UN3107 | ≤100 | OP8 | |||||||

| Peroxyacetic acid, type D, stabilized | UN3105 | ≤43 | OP7 | 13, 20 | ||||||

| Peroxyacetic acid, type E, stabilized | UN3107 | ≤43 | OP8 | 13, 20 | ||||||

| Peroxyacetic acid, type F, stabilized | UN3109 | ≤43 | OP8 | 13, 20, 28 | ||||||

| Peroxyacetic acid or peracetic acid [with not more than 7% hydrogen peroxide] | UN3107 | ≤36 | ≥15 | OP8 | 13, 20, 28 | |||||

| Peroxyacetic acid or peracetic acid [with not more than 20% hydrogen peroxide] | Exempt | ≤6 | ≥60 | Exempt | 28 | |||||

| Peroxyacetic acid or peracetic acid [with not more than 26% hydrogen peroxide] | UN3109 | ≤17 | OP8 | 13, 20, 28 | ||||||

| Peroxylauric acid | UN3118 | ≤100 | OP8 | +35 | +40 | |||||

| 1-Phenylethyl hydroperoxide | UN3109 | ≤38 | ≥62 | OP8 | ||||||

| Pinanyl hydroperoxide | UN3105 | >56−100 | OP7 | 13 | ||||||

| Pinanyl hydroperoxide | UN3109 | ≤56 | ≥44 | OP8 | ||||||

| Polyether poly-tert-butylperoxycarbonate | UN3107 | ≤52 | ≥48 | OP8 | ||||||

| Tetrahydronaphthyl hydroperoxide | UN3106 | ≤100 | OP7 | |||||||

| 1,1,3,3-Tetramethylbutyl hydroperoxide | UN3105 | ≤100 | OP7 | |||||||

| 1,1,3,3-Tetramethylbutyl peroxy-2-ethylhexanoate | UN3115 | ≤100 | OP7 | +15 | +20 | |||||

| 1,1,3,3-Tetramethylbutyl peroxyneodecanoate | UN3115 | ≤72 | ≥28 | OP7 | −5 | +5 | ||||

| 1,1,3,3-Tetramethylbutyl peroxyneodecanoate [as a stable dispersion in water] | UN3119 | ≤52 | OP8 | −5 | +5 | |||||

| 1,1,3,3-tetramethylbutyl peroxypivalate | UN3115 | ≤77 | ≥23 | OP7 | 0 | +10 | ||||

| 3,6,9-Triethyl-3,6,9-trimethyl-1,4,7-triperoxonane | UN3110 | ≤17 | ≥18 | ≥65 | OP8 | |||||

| 3,6,9-Triethyl-3,6,9-trimethyl-1,4,7-triperoxonane | UN3105 | ≤42 | ≥58 | OP7 | 26 | |||||

| Notes: | ||||||||||

| 1. For domestic shipments, OP8 is authorized. | ||||||||||

| 2. Available oxygen must be <4.7%. | ||||||||||

| 3. For concentrations <80% OP5 is allowed. For concentrations of at least 80% but <85%, OP4 is allowed. For concentrations of at least 85%, maximum package size is OP2. | ||||||||||

| 4. The diluent may be replaced by di-tert-butyl peroxide. | ||||||||||

| 5. Available oxygen must be ≤9% with or without water. | ||||||||||

| 6. For domestic shipments, OP5 is authorized. | ||||||||||

| 7. Available oxygen must be ≤8.2% with or without water. | ||||||||||

| 8. Only non-metallic packagings are authorized. | ||||||||||

| 9. For domestic shipments this material may be transported under the provisions of paragraph (h)(3)(xii) of this section. | ||||||||||

| 10. [Reserved] | ||||||||||

| 11. [Reserved] | ||||||||||

| 12. Samples may only be offered for transportation under the provisions of paragraph (b)(2) of this section. | ||||||||||

| 13. “Corrosive” subsidiary risk label is required. | ||||||||||

| 14. [Reserved] | ||||||||||

| 15. No “Corrosive” subsidiary risk label is required for concentrations below 80%. | ||||||||||

| 16. With <6% di-tert-butyl peroxide. | ||||||||||

| 17. With ≤8% 1-isopropylhydroperoxy-4-isopropylhydroxybenzene. | ||||||||||

| 18. Addition of water to this organic peroxide will decrease its thermal stability. | ||||||||||

| 19. [Reserved] | ||||||||||

| 20. Mixtures with hydrogen peroxide, water and acid(s). | ||||||||||

| 21. With diluent type A, with or without water. | ||||||||||

| 22. With ≥36% diluent type A by mass, and in addition ethylbenzene. | ||||||||||

| 23. With ≥19% diluent type A by mass, and in addition methyl isobutyl ketone. | ||||||||||

| 24. Diluent type B with boiling point >100 C. | ||||||||||

| 25. No “Corrosive” subsidiary risk label is required for concentrations below 56%. | ||||||||||

| 26. Available oxygen must be ≤7.6%. | ||||||||||

| 27. Formulations derived from distillation of peroxyacetic acid originating from peroxyacetic acid in a concentration of not more than 41% with water, total active oxygen less than or equal to 9.5% (peroxyacetic acid plus hydrogen peroxide). | ||||||||||

| 28. For the purposes of this section, the names “Peroxyacetic acid” and “Peracetic acid” are synonymous. | ||||||||||

| 29. Not subject to the requirements of this subchapter for Division 5.2. | ||||||||||

| 30. Diluent type B with boiling point >130°C (266°F). | ||||||||||

| 31. Available oxygen ≤6.7%. | ||||||||||

(d) *****

Table to Paragraph (d): Maximum Quantity per Packaging/Package

* * * * *

(g) * * *

| UN No. | Hazardous material | Minimum test pressure (bar) | Minimum shell thickness (mm-reference steel) See . . . | Bottom opening requirements See . . . | Pressure-relief requirements See . . . | Filling limits | Control temperature | Emergency temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3109 | ORGANIC PEROXIDE, TYPE F, LIQUID | |||||||

|

tert-Butyl hydroperoxide, not more than 72% with water.

*Provided that steps have been taken to achieve the safety equivalence of 65% tert-Butyl hydroperoxide and 35% water. | 4 | §178.274(d)(2) | §178.275(d)(3) | §178.275(g)(1) | Not more than 90% at 59°F (15°C) | |||

| * * * * | * * * * | * * * * | * * * * | * * * * | * * * * | * * * * | * * * * | * * * * |

| Note: 1. “Corrosive” subsidiary risk placard is required. | ||||||||

* * * * *

§173.301b Additional general requirements for shipment of UN pressure receptacles.

* * * * *

(c) * * *

(1) When the use of a valve is prescribed, the valve must conform to the requirements in ISO 10297:2014(E) and ISO 10297:2014/Amd 1:2017 (IBR, see §171.7 of this subchapter). Quick release cylinder valves for specification and type testing must conform to the requirements in ISO 17871:2015(E) (IBR, see §171.7 of this subchapter). Until December 31, 2022, the manufacture of a valve conforming to the requirements in ISO 10297:2014(E) is authorized. Until December 31, 2020, the manufacture of a valve conforming to the requirements in ISO 10297:2006(E) (IBR, see §171.7 of this subchapter) was authorized. Until December 31, 2008, the manufacture of a valve conforming to the requirements in ISO 10297:1999(E) (IBR, see §171.7 of this subchapter) was authorized.

(2) * * *