EPA Final Rule: Technology Transitions Program for Phasedown of Hydrofluorocarbons

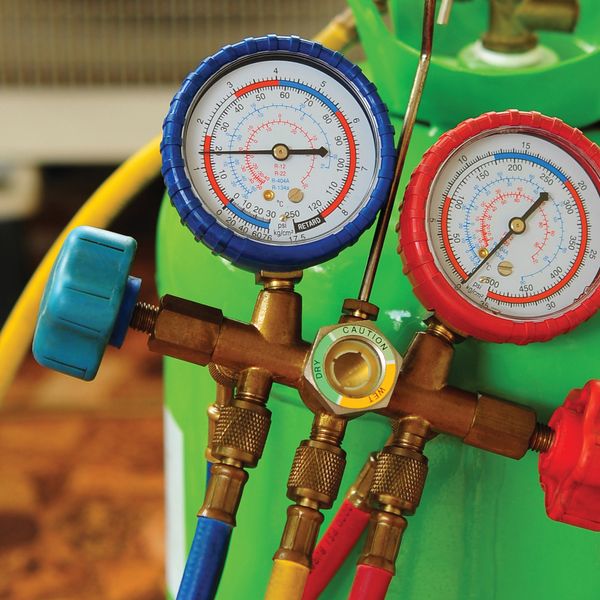

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is amending a provision of the recently finalized Technology Transitions Program under the American Innovation and Manufacturing Act (AIM Act). This action allows one additional year, until January 1, 2026, solely for the installation of new residential and light commercial air conditioning and heat pump systems using components manufactured or imported prior to January 1, 2025. The existing January 1, 2025, compliance date for the installation of certain residential and light commercial air conditioning and heat pump systems may result in significant stranded inventory that was intended for new residential construction. EPA is promulgating this action to mitigate the potential for significant stranded inventory in this subsector. In addition, EPA is clarifying that residential ice makers are not included in the household refrigerator and freezer subsector under the Technology Transitions Rule and are not subject to the restrictions for that subsector. EPA is requesting comments on all aspects of this rule.

DATES: This interim final rule is effective on December 26, 2023, published in the Federal Register December 26, 2023, page 88825.

View final rule.

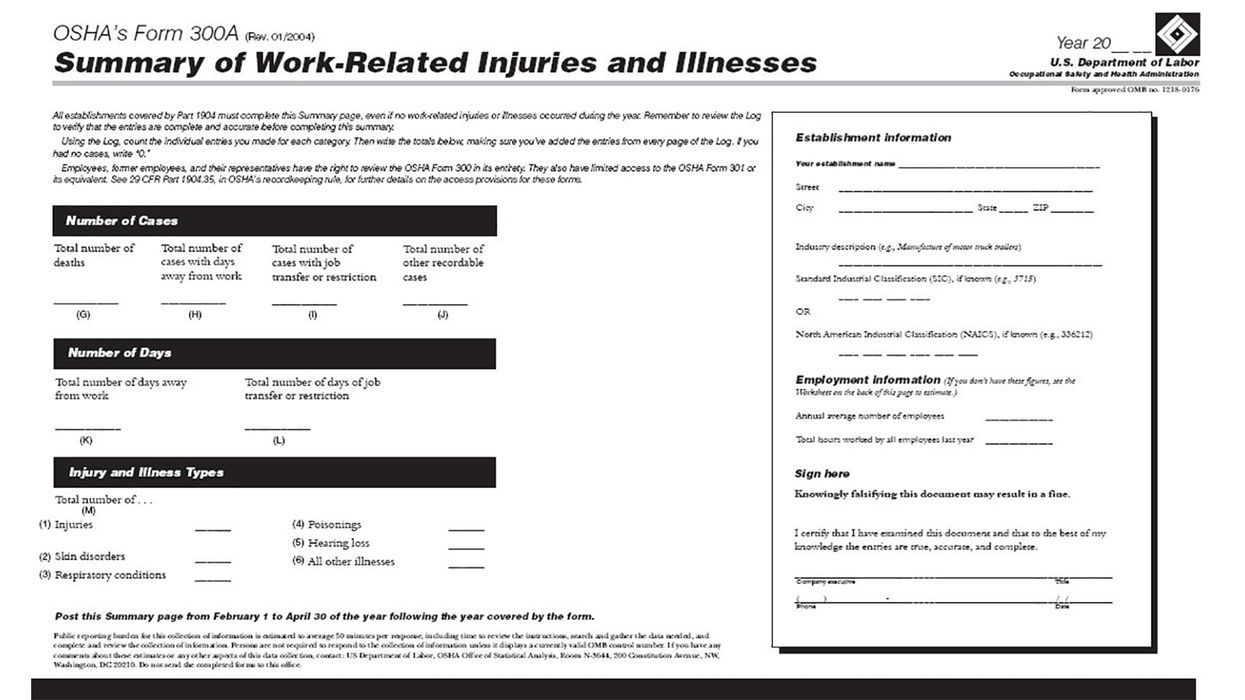

| §84.54 Restrictions on the use of hydrofluorocarbons. | ||

| (c)(1) | Revised | View text |

Previous Text

§84.54 Restrictions on the use of hydrofluorocarbons.

* * * * *

(c) * * *

(1) Effective January 1, 2025, residential or light commercial air-conditioning or heat pump systems using a regulated substance, or a blend containing a regulated substance, with a global warming potential of 700 or greater, except for variable refrigerant flow air-conditioning and heat pump systems;

* * * * *