86 FR 73131 Revisions to the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) for Public Water Systems and Announcement of Public Meetings

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

40 CFR Part 141

[EPA-HQ-OW-2020-0530; FRL-6791-03-OW]

RIN 2040-AF89

Revisions to the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) for Public Water Systems and Announcement of Public Meetings

AGENCY: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

ACTION: Final rule and notice of public meetings.

SUMMARY: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is finalizing a Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) rule that requires certain public water systems (PWSs) to collect national occurrence data for 29 per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and lithium. Subject to the availability of appropriations, EPA will include all systems serving 3,300 or more people and a representative sample of 800 systems serving 25 to 3,299 people. If EPA does not receive the appropriations needed for monitoring all of these systems in a given year, EPA will reduce the number of systems serving 25 to 10,000 people that will be asked to perform monitoring. This final rule is a key action to ensure science-based decision-making and prioritize protection of disadvantaged communities in accordance with EPA's PFAS Strategic Roadmap. EPA is also announcing plans for public webinars to discuss implementation of the fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5).

DATES: This final rule is effective on January 26, 2022. The incorporation by reference of certain publications listed in this final rule is approved by the Director of the Federal Register as of January 26, 2022.

ADDRESSES: EPA has established a docket for this action under Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OW-2020-0530. All documents in the docket are listed on the https://www.regulations.gov website. Although listed in the index, some information is not publicly available, e.g., CBI or other information whose disclosure is restricted by statute. Certain other material, such as copyrighted material, is not placed on the internet and will be publicly available only in hard copy form. Publicly available docket materials are available electronically through https://www.regulations.gov.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Brenda D. Bowden, Standards and Risk Management Division (SRMD), Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water (OGWDW) (MS 140), Environmental Protection Agency, 26 West Martin Luther King Drive, Cincinnati, Ohio 45268; telephone number: (513) 569-7961; email address: bowden.brenda@epa.gov; or Melissa Simic, SRMD, OGWDW (MS 140), Environmental Protection Agency, 26 West Martin Luther King Drive, Cincinnati, Ohio 45268; telephone number: (513) 569-7864; email address: simic.melissa@epa.gov. For general information, visit the Ground Water and Drinking Water web page at: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Table of Contents

I. Summary Information

A. Purpose of the Regulatory Action

1. What action is EPA taking?

2. Does this action apply to me?

3. What is EPA's authority for taking this action?

4. What is the applicability date?

B. Summary of the Regulatory Action

C. Economic Analysis

1. What is the estimated cost of this action?

2. What are the benefits of this action?

II. Public Participation

A. What meetings have been held in preparation for UCMR 5?

B. How do I participate in the upcoming meetings?

1. Meeting Participation

2. Meeting Materials

III. General Information

A. How are CCL, UCMR, Regulatory Determination process, and NCOD interrelated?

B. What are the Consumer Confidence Reporting and Public Notice Reporting requirements for public water systems that are subject to UCMR?

C. What is the UCMR 5 timeline?

D. What is the role of “States” in UCMR?

E. How did EPA consider Children's Environmental Health?

F. How did EPA address Environmental Justice?

G. How did EPA coordinate with Indian Tribal Governments?

H. How are laboratories approved for UCMR 5 analyses?

1. Request To Participate

2. Registration

3. Application Package

4. EPA's Review of Application Package

5. Proficiency Testing

6. Written EPA Approval

I. What documents are being incorporated by reference?

1. Methods From the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

2. Alternative Methods From American Public Health Association—Standard Methods (SM)

3. Methods From ASTM International

IV. Description of Final Rule and Summary of Responses to Public Comments

A. What contaminants must be monitored under UCMR 5?

1. This Final Rule

2. Summary of Major Comments and EPA Responses

a. Aggregate PFAS Measure

b. Legionella Pneumophila

c. Haloacetonitriles

d. 1,2,3-Trichloropropane

B. What is the UCMR 5 sampling design?

1. This Final Rule

2. Summary of Major Comments and EPA Responses

C. What is the sampling frequency and timing?

1. This Final Rule

2. Summary of Major Comments and EPA Responses

D. Where are the sampling locations and what is representative monitoring?

1. This Final Rule

2. Summary of Major Comments and EPA Responses

E. How long do laboratories and PWSs have to report data?

1. This Final Rule

2. Summary of Major Comments and EPA Responses

F. What are the reporting requirements for UCMR 5?

1. This Final Rule

2. Summary of Major Comments and EPA Responses

a. Data Elements

b. Reporting State Data

G. What are the UCMR 5 Minimum Reporting Levels (MRLs) and how were they determined?

1. This Final Rule

2. Summary of Major Comments and EPA Responses

H. What are the requirements for laboratory analysis of field reagent blank samples?

1. This Final Rule

2. Summary of Major Comments and EPA Responses

I. How will EPA support risk communication for UCMR 5 results?

V. Statutory and Executive Order Reviews

A. Executive Order 12866: Regulatory Planning and Review and Executive Order 13563: Improving Regulation and Regulatory Review

B. Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA)

C. Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA)

D. Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (UMRA)

E. Executive Order 13132: Federalism

F. Executive Order 13175: Consultation and Coordination With Indian Tribal Governments

G. Executive Order 13045: Protection of Children From Environmental Health Risks and Safety Risks

H. Executive Order 13211: Actions Concerning Regulations That Significantly Affect Energy Supply, Distribution or Use

I. National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act (NTTAA)

J. Executive Order 12898: Federal Actions To Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations

K. Congressional Review Act (CRA)

VI. References

Abbreviations and Acronyms

μg/L Microgram per Liter

11Cl-PF3OUdS 11-chloroeicosafluoro-3-oxaundecane-1-sulfonic Acid

4:2 FTS 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H-perfluorohexane Sulfonic Acid

6:2 FTS 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H-perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid

8:2 FTS 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H-perfluorodecane Sulfonic Acid

9Cl-PF3ONS 9-chlorohexadecafluoro-3-oxanone-1-sulfonic Acid

ADONA 4,8-dioxa-3H-perfluorononanoic Acid

AES Atomic Emission Spectrometry

ASDWA Association of State Drinking Water Administrators

ASTM ASTM International

AWIA America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018

CASRN Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number

CBI Confidential Business Information

CCL Contaminant Candidate List

CCR Consumer Confidence Report

CFR Code of Federal Regulations

CRA Congressional Review Act

CWS Community Water System

DBP Disinfection Byproduct

DWSRF Drinking Water State Revolving Fund

EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency

EPTDS Entry Point to the Distribution System

FR Federal Register

FRB Field Reagent Blank

GW Ground Water

GWRMP Ground Water Representative Monitoring Plan

HFPO-DA Hexafluoropropylene Oxide Dimer Acid (GenX)

HRL Health Reference Level

ICP Inductively Coupled Plasma

ICR Information Collection Request

IDC Initial Demonstration of Capability

LCMRL Lowest Concentration Minimum Reporting Level

LC/MS/MS Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry

MDBP Microbial and Disinfection Byproduct

MRL Minimum Reporting Level

NAICS North American Industry Classification System

NCOD National Contaminant Occurrence Database

NDAA National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020

NEtFOSAA N-ethyl Perfluorooctanesulfonamidoacetic Acid

NFDHA Nonafluoro‐3,6‐dioxaheptanoic Acid

ng/L Nanogram per Liter

NMeFOSAA N-methyl Perfluorooctanesulfonamidoacetic Acid

NPDWR National Primary Drinking Water Regulation

NTNCWS Non-transient Non-community Water System

NTTAA National Technology Transfer and Advancement Act

NTWC National Tribal Water Council

OGWDW Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water

OMB Office of Management and Budget

PFAS Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances

PFBA Perfluorobutanoic Acid

PFBS Perfluorobutanesulfonic Acid

PFDA Perfluorodecanoic Acid

PFDoA Perfluorododecanoic Acid

PFEESA Perfluoro (2‐ethoxyethane) Sulfonic Acid

PFHpA Perfluoroheptanoic Acid

PFHpS Perfluoroheptanesulfonic Acid

PFHxA Perfluorohexanoic Acid

PFHxS Perfluorohexanesulfonic Acid

PFMBA Perfluoro‐4‐methoxybutanoic Acid

PFMPA Perfluoro‐3‐methoxypropanoic Acid

PFNA Perfluorononanoic Acid

PFOA Perfluorooctanoic Acid

PFOS Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid

PFPeA Perfluoropentanoic Acid

PFPeS Perfluoropentanesulfonic Acid

PFTA Perfluorotetradecanoic Acid

PFTrDA Perfluorotridecanoic Acid

PFUnA Perfluoroundecanoic Acid

PN Public Notice

PRA Paperwork Reduction Act

PT Proficiency Testing

PWS Public Water System

QC Quality Control

RFA Regulatory Flexibility Act

SBA Small Business Administration

SBREFA Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act

SDWA Safe Drinking Water Act

SDWARS Safe Drinking Water Accession and Review System

SDWIS/Fed Safe Drinking Water Information System Federal Reporting Services

SM Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater

SOP Standard Operating Procedure

SPE Solid Phase Extraction

SRMD Standards and Risk Management Division

SW Surface Water

SWTR Surface Water Treatment Rule

TNCWS Transient Non-community Water System

TOF Total Organic Fluorine

TOP Total Oxidizable Precursors

UCMR Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule

UMRA Unfunded Mandates Reform Act of 1995

U.S. United States

USEPA United States Environmental Protection Agency

I. Summary Information

A. Purpose of the Regulatory Action

1. What action is EPA taking?

This final rule requires certain public water systems (PWSs), described in section I.A.2 of this preamble, to collect national occurrence data for 29 PFAS and lithium. PFAS and lithium are not currently subject to national primary drinking water regulations, and EPA is requiring collection of data under UCMR 5 to inform EPA regulatory determinations and risk-management decisions. Consistent with EPA's PFAS Strategic Roadmap, UCMR 5 will provide new data critically needed to improve EPA's understanding of the frequency that 29 PFAS (and lithium) are found in the nation's drinking water systems and at what levels. This data will ensure science-based decision-making and help prioritize protection of disadvantaged communities.

2. Does this action apply to me?

This final rule applies to PWSs described in this section. PWSs are systems that provide water for human consumption through pipes, or constructed conveyances, to at least 15 service connections or that regularly serve an average of at least 25 individuals daily at least 60 days out of the year. A community water system (CWS) is a PWS that has at least 15 service connections used by year-round residents or regularly serves at least 25 year-round residents. A non-transient non-community water system (NTNCWS) is a PWS that is not a CWS and that regularly serves at least 25 of the same people over 6 months per year. Under this final rule, all large CWSs and NTNCWSs serving more than 10,000 people are required to monitor. In addition, small CWSs and NTNCWSs serving between 3,300 and 10,000 people are required to monitor (subject to available EPA appropriations and EPA notification of such requirement) as are the PWSs included in a nationally representative sample of CWSs and NTNCWSs serving between 25 and 3,299 people (see “Selection of Nationally Representative Public Water Systems for the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule: 2021 Update” for a description of the statistical approach for EPA's selection of the nationally representative sample (USEPA, 2021a), available in the UCMR 5 public docket). EPA expects to clarify the monitoring responsibilities for affected small systems by approximately July 1 of each year preceding sample collection, based on the availability of appropriations each year.

As in previous UCMRs, transient non-community water systems (TNCWSs) ( i.e., non-community water systems that do not regularly serve at least 25 of the same people over 6 months per year) are not required to monitor under UCMR 5. EPA leads UCMR 5 monitoring as a direct-implementation program. States, Territories, and Tribes with primary enforcement responsibility (primacy) to administer the regulatory program for PWSs under SDWA (hereinafter collectively referred to in this document as “states”), can participate in the implementation of UCMR 5 through voluntary Partnership Agreements (see discussion of Partnership Agreements in Section III.D of this preamble). Under Partnership Agreements, states can choose to be involved in various aspects of UCMR 5 monitoring for PWSs they oversee; however, the PWS remains responsible for compliance with the final rule. Potentially regulated categories and entities are identified in the following table.

| Category | Examples of potentially regulated entities | NAICS * |

|---|---|---|

| * NAICS = North American Industry Classification System. | ||

| State, local, & Tribal governments | State, local, and Tribal governments that analyze water samples on behalf of PWSs required to conduct such analysis; State, local, and Tribal governments that directly operate CWSs and NTNCWSs required to monitor | 924110 |

| Industry | Private operators of CWSs and NTNCWSs required to monitor | 221310 |

| Municipalities | Municipal operators of CWSs and NTNCWSs required to monitor | 924110 |

This table is not intended to be exhaustive, but rather provides a guide for readers regarding entities likely to be regulated by this action. This table lists the types of entities that EPA is aware could potentially be regulated by this action. Other types of entities not listed in the table could also be regulated. To determine whether your entity is regulated by this action, you should carefully examine the definition of PWS found in Title 40 in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) at 40 CFR 141.2 and 141.3, and the applicability criteria found in 40 CFR 141.40(a)(1) and (2). If you have questions regarding the applicability of this action to a particular entity, please consult the contacts listed in the preceding FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT section of this preamble.

3. What is EPA's authority for taking this action?

As part of EPA's responsibilities under SDWA, the agency implements section 1445(a)(2), Monitoring Program for Unregulated Contaminants. This section, as amended in 1996, requires that once every five years, beginning in August 1999, EPA issue a list of not more than 30 unregulated contaminants to be monitored by PWSs. SDWA requires that EPA enter the monitoring data into the agency's publicly available National Contaminant Occurrence Database (NCOD) at https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/national-contaminant-occurrence-database-ncod.

EPA must vary the frequency and schedule for monitoring based on the number of people served, the source of supply, and the contaminants likely to be found. EPA is using SDWA Section 1445(a)(2) authority as the basis for monitoring the unregulated contaminants under this final rule.

Section 2021 of America's Water Infrastructure Act of 2018 (AWIA) (Pub. L. 115-270) amended SDWA and specifies that, subject to the availability of EPA appropriations for such purpose and sufficient laboratory capacity, EPA's UCMR program must require all PWSs serving between 3,300 and 10,000 people to monitor for the contaminants in a particular UCMR cycle, and ensure that only a nationally representative sample of systems serving between 25 and 3,299 people are required to monitor for those contaminants. EPA has developed this final rule anticipating that necessary appropriations will become available; however, to date, Congress has not appropriated additional funding ( i.e., funding in addition to the $2.0 million that EPA has historically set aside each year from the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund, using SDWA authority, to support UCMR monitoring at small systems) to cover monitoring expenses for all PWSs serving between 3,300 and 10,000 people. Provisions in the final rule enable the agency to adjust the number of these systems that must monitor based upon available appropriations.

AWIA did not amend the original SDWA requirements for large PWSs. Therefore, PWSs serving a population larger than 10,000 people continue to be responsible for participating in UCMR.

Section 7311 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 (NDAA) (Pub. L. 116-92) amended SDWA and specifies that EPA shall include all PFAS in UCMR 5 for which a drinking water method has been validated by the Administrator and that are not subject to a national primary drinking water regulation.

4. What is the applicability date?

The applicability date represents an internal milestone used by EPA to determine if a PWS is included in the UCMR program and whether it will be treated as small ( i.e., serving 25 to 10,000 people) or large ( i.e., serving more than 10,000 people). It does not represent a date by which respondents need to take any action. The determination of whether a PWS is required to monitor under UCMR 5 is based on the type of system ( e.g., CWS, NTNCWS, etc.) and its retail population served, as indicated by the Safe Drinking Water Information System Federal Reporting Services (SDWIS/Fed) inventory on February 1, 2021. SDWIS/Fed can be accessed at https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/safe-drinking-water-information-system-sdwis-federal-reporting. Examining water system type and population served as of February 1, 2021 allowed EPA to develop a draft list of PWSs tentatively subject to UCMR 5 and share that list with the states during 2021 for their review. This advance planning and review then allowed EPA to load state-reviewed PWS information into EPA's reporting system so that those PWSs can be promptly notified upon publication of this final rule. If a PWS receives such notification and believes it has been erroneously included in UCMR 5 based on an incorrect retail population, the system should contact their state authority to verify its population served as of the applicability date. If an error impacting rule applicability is identified, the state or the PWS may contact EPA to address the error. The 5-year UCMR 5 cycle spans January 2022 through December 2026, with preparations in 2022, sample collection between January 1, 2023, and December 31, 2025, and completion of data reporting in 2026. By approximately July 1 of the year prior to each year's sample collection ( i.e., by July 1, 2022 for 2023 sampling; by July 1, 2023 for 2024 sampling; and by July 1, 2024 for 2025 sampling) EPA expects to determine whether it has received necessary appropriations to support its plan to monitor at all systems serving between 3,300 and 10,000 people and at a representative group of 800 smaller systems. As EPA finalizes its small-system plan for each sample collection year, the agency will notify the small PWSs accordingly.

B. Summary of the Regulatory Action

EPA is requiring certain PWSs to collect occurrence data for 29 PFAS and lithium. This document addresses key aspects of UCMR 5, including the following: Analytical methods to measure the contaminants; laboratory approval; monitoring timeframe; sampling locations; data elements ( i.e., information required to be collected along with the occurrence data); data reporting timeframes; monitoring cost; public participation; conforming and editorial changes, such as those necessary to remove requirements solely related to UCMR 4; and EPA responses to public comments on the proposed rule. This document also discusses the implication for UCMR 5 of the AWIA Section 2021(a) requirement that EPA collect monitoring data from all systems serving more than 3,300 people “subject to the availability of appropriations.”

Regardless of whether EPA is able to carry out the small-system monitoring as planned, or instead reduces the scope of that monitoring, the small-system data collection, coupled with data collection from all systems serving more than 10,000 people under this action, will provide scientifically valid data on the national occurrence of 29 PFAS and lithium in drinking water. The UCMR data are the primary source of national occurrence data that EPA uses to inform regulatory and other risk management decisions for drinking water contaminant candidates.

EPA is required under SDWA Section 1445(a)(2)(C)(ii) to pay the “reasonable cost of such testing and laboratory analysis” for all applicable PWSs serving 25 to 10,000 people. Consistent with AWIA, EPA will require monitoring at as many systems serving 3,300 to 10,000 people as appropriations support (see Section IV.B of this preamble for more information on the agency's sampling design).

The agency received several public comments expressing concern that significant laboratory capacity will be needed to support the full scope envisioned for UCMR 5 PFAS monitoring. EPA anticipates that sufficient laboratory capacity will exist to support the expanded UCMR 5 scope. EPA's experience over the first four cycles of UCMR implementation has been that laboratory capacity quickly grows to meet UCMR demand. EPA also notes that the number of laboratories successfully participating in the early stages of the UCMR 5 laboratory approval program is a good indicator that there will be a robust national network of laboratories experienced in PFAS drinking water analysis.

By early 2022, EPA will notify all small CWSs and NTNCWSs serving between 3,300 and 10,000 people of their anticipated requirement to monitor, which EPA expects to confirm and schedule by July 1 preceding each collection year based on the availability of appropriations. The nationally representative sample of smaller PWSs described in Section I.A of this preamble will be similarly notified and advised of their schedules.

This final rule addresses the requirements of the NDAA by including all 29 PFAS that are within the scope of EPA Methods 533 and 537.1. Both of these methods have been validated by EPA for drinking water analysis.

C. Economic Analysis

1. What is the estimated cost of this action?

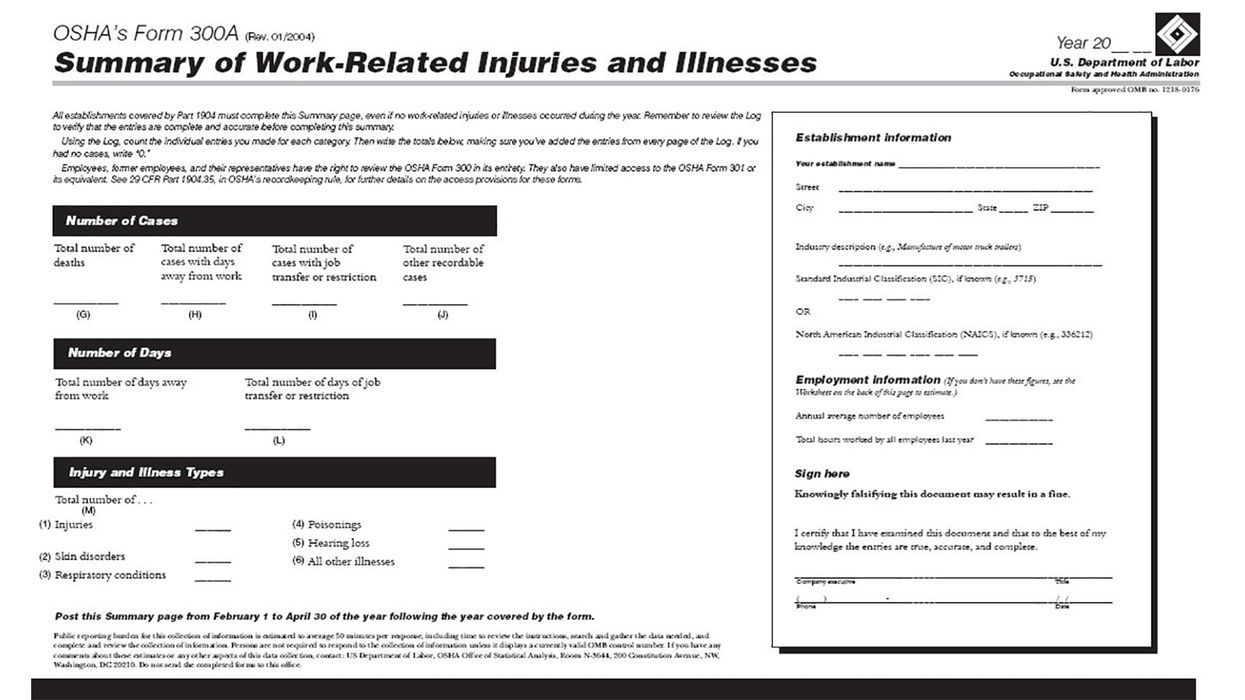

EPA estimates the total average national cost of this action would be $21 million per year over the 5-year effective period of the final rule (2022-2026) assuming EPA collects information from all systems serving between 3,300 and 10,000 people. All of these costs are associated with paperwork burden under the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA). EPA discusses the expected costs as well as documents the assumptions and data sources used in the preparation of this estimate in the “Information Collection Request for the Final Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5)” (USEPA, 2021b). Costs are incurred by large PWSs (for sampling and analysis); small PWSs (for sampling); state regulatory agencies ( i.e., those who volunteer to assist EPA with oversight and implementation support); and EPA (for regulatory support and oversight activities, and analytical and shipping costs for samples from small PWSs). These costs are also summarized in Exhibit 1 of this preamble. EPA's estimates are based on executing the full monitoring plan for small systems ( i.e., including all systems serving 3,300 to 10,000 people and a representative group of 800 smaller systems). As such, those estimates represent an upper bound. If EPA does not receive the necessary appropriations in one or more of the collections years—and thus collects data from fewer small systems—the actual costs would be lower than those estimated here.

EPA received several comments on the cost of monitoring. EPA has accounted for the cost/burden associated with all of the PWS activities as part of the comprehensive cost/burden estimates. In order to provide the most accurate and updated cost estimate, EPA re-examined labor burden estimates for states, EPA, and PWS activities and updated costs of laboratory services for sample analysis, based on consultations with national drinking water laboratories, when developing this final rule.

The costs for a particular UCMR cycle are heavily influenced by the selection of contaminants and associated analytical methods. EPA identified three EPA-developed analytical methods (and, in the case of lithium, multiple optional alternative methods) to analyze samples for UCMR 5 contaminants. EPA's estimate of the UCMR 5 analytical cost is $740 per sample set ( i.e., $740 to analyze a set of samples from one sample point and one sample event for the 30 UCMR 5 contaminants).

Exhibit 1 of this preamble details the EPA-estimated annual average national costs (accounting for labor and non-labor expenses). Laboratory analysis and sample shipping account for approximately 65 percent of the estimated total national cost for the implementation of UCMR 5. EPA estimated laboratory costs based on consultations with multiple commercial drinking water testing laboratories. EPA's cost estimates for the laboratory methods include shipping and analysis.

EPA expects that states will incur modest labor costs associated with voluntary assistance with the implementation of UCMR 5. EPA estimated state costs using the relevant assumptions from the State Resource Model developed by the Association of State Drinking Water Administrators (ASDWA) (ASDWA, 2013) to help states forecast resource needs. Model estimates were adjusted to account for actual levels of state participation under UCMR 4. State assistance with EPA's implementation of UCMR 5 is voluntary; thus, the level of effort is expected to vary among states and will depend on their individual agreements with EPA.

EPA assumes that one-third of the systems will collect samples during each of the three sample-collection years from January 2023 through December 2025.

| Entity | Average annual cost (million) (2022-2026) 2 |

|---|---|

| 1 Based on the scope of small-system monitoring described in AWIA. | |

| 2 Totals may not equal the sum of components due to rounding. | |

| 3 Labor costs pertain to PWSs, states, and EPA. Costs include activities such as reading the final rule, notifying systems selected to participate, sample collection, data review, reporting, and record keeping. | |

| 4 Non-labor costs will be incurred primarily by EPA and by large and very large PWSs. They include the cost of shipping samples to laboratories for testing and the cost of the laboratory analyses. | |

| 5 For a typical UCMR program that involves the expanded scope prescribed by AWIA, EPA estimates an average annual cost to the agency of $17M/year (over a 5-year cycle) ($2M/year for the representative sample of 800 PWSs serving between 25 and 3,299 people and $15M/year for all PWSs serving between 3,300 and 10,000 people). The projected cost to EPA for UCMR 5 implementation is lower than for a typical UCMR program because of lower sample analysis expenses. Those lower expenses are a result of analytical method efficiencies ( i.e., being able to monitor for 30 chemicals with only three analytical methods). | |

| Small PWSs (25-10,000), including labor 3 only (non-labor costs 4 paid for by EPA) | $0.3 |

| Large PWSs (10,001-100,000), including labor and non-labor costs | 7.0 |

| Very Large PWSs (100,001 and greater), including labor and non-labor costs | 2.2 |

| States, including labor costs related to implementation coordination | 0.8 |

| EPA, including labor for implementation and non-labor for small system testing | 5 10.5 |

| Average Annual National Total | 20.8 |

Additional details regarding EPA's cost assumptions and estimates can be found in the Information Collection Request (ICR) (USEPA, 2021b), ICR Number 2040-0304, which presents estimated cost and labor hours for the 5-year UCMR 5 period of 2022-2026. Copies of the ICR may be obtained from the EPA public docket for this final rule under Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OW-2020-0530.

2. What are the benefits of this action?

The public benefits from the information about whether or not unregulated contaminants are present in their drinking water. If contaminants are not found, consumer confidence in their drinking water should improve. If contaminants are found, related health effects may be avoided when subsequent actions, such as regulations, are implemented, reducing or eliminating those contaminants.

II. Public Participation

A. What meetings have been held in preparation for UCMR 5?

EPA held three public meetings on UCMR 5 over the period of 2018 through 2021. EPA held a meeting focused on drinking water methods for unregulated contaminants on June 6, 2018, in Cincinnati, Ohio. Representatives from state agencies, laboratories, PWSs, environmental organizations, and drinking water associations joined the meeting via webinar and in person. Meeting topics included an overview of regulatory process elements (including the Contaminant Candidate List (CCL), UCMR, and Regulatory Determination), and drinking water methods under development (see USEPA, 2018 for presentation materials). EPA held a second meeting on July 16, 2019, in Cincinnati, Ohio. Representatives from State agencies, Tribes, laboratories, PWSs, environmental organizations, and drinking water associations participated in the meeting via webinar and in person. Meeting topics included the impacts of AWIA, analytical methods and contaminants being considered by EPA, potential sampling design, and other possible aspects of the UCMR 5 approach (see USEPA, 2019a for meeting materials). EPA held two identical virtual meetings on April 6 and 7, 2021, during the public comment period for the proposed rule (see USEPA, 2021c for presentation materials). Topics included the proposed UCMR 5 monitoring requirements, analyte selection and rationale, analytical methods, the laboratory approval process, and ground water representative monitoring plans (GWRMPs). Representatives of state agencies, laboratories, PWSs, environmental organizations, and drinking water associations participated in the meeting via webinar. In Section II.B of this preamble, the agency is announcing additional meetings to be held in 2022, which will assist with implementation.

B. How do I participate in the upcoming meetings?

EPA will hold multiple virtual meetings during 2022 to discuss UCMR 5 implementation planning, data reporting using Safe Drinking Water Accession and Review System (SDWARS), and best practices for sample collection. Dates and times of the upcoming meetings will be posted on EPA's website at https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr/unregulated-contaminant-monitoring-rule-ucmr-meetings-and-materials. EPA anticipates hosting the meetings focused on implementation planning in spring 2022, and the SDWARS and sample-collection meetings in fall 2022. Stakeholders who have participated in past UCMR meetings and/or those who register to use SDWARS will receive notification of these events. Other interested stakeholders are also welcome to participate.

1. Meeting Participation

Those who wish to participate in the public meetings, via webinar, can find information on how to register at https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr/unregulated-contaminant-monitoring-rule-ucmr-meetings-and-materials. The number of webinar connections available for the meetings are limited and will be available on a first-come, first-served basis. If stakeholder interest results in exceeding the maximum number of available connections for participants in upcoming webinar offerings, EPA may schedule additional webinars, with dates and times posted on EPA's Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Program Meetings and Materials web page at https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr/unregulated-contaminant-monitoring-rule-ucmr-meetings-and-materials.

2. Meeting Materials

EPA expects to send meeting materials by email to all registered participants prior to the meeting. The materials will be posted on EPA's website at https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr/unregulated-contaminant- monitoring-rule-ucmr-meetings-and-materials for people who do not participate in the webinar.

III. General Information

A. How are CCL, UCMR, Regulatory Determination process, and NCOD interrelated?

Under the 1996 amendments to SDWA, Congress established a multi-step, risk-based approach for determining which contaminants would become subject to drinking water standards. Under the first step, EPA is required to publish a CCL every five years that identifies contaminants that are not subject to any proposed or promulgated drinking water regulations, are known or anticipated to occur in PWSs, and may require future regulation under SDWA. EPA published the draft CCL 5 in the Federal Register on July 19, 2021 (86 FR 37948, July 19, 2021 (USEPA, 2021d)). Under the second step, EPA must require, every five years, monitoring of unregulated contaminants as described in this action. The third step requires EPA to determine, every five years, whether or not to regulate at least five contaminants from the CCL. Under Section 1412(b)(1)(A) of SDWA, EPA regulates a contaminant in drinking water if the Administrator determines that:

(1) The contaminant may have an adverse effect on the health of persons;

(2) The contaminant is known to occur or there is substantial likelihood that the contaminant will occur in PWSs with a frequency and at levels of public health concern; and

(3) In the sole judgment of the Administrator, regulation of such contaminant presents a meaningful opportunity for health risk reduction for persons served by PWSs.

For the contaminants that meet all three criteria, SDWA requires EPA to publish national primary drinking water regulations (NPDWRs). Information on the CCL and the regulatory determination process can be found at: https://www.epa.gov/ccl.

The data collected through the UCMR program are made available to the public through the National Contaminant Occurrence Database (NCOD) for drinking water. EPA developed the NCOD to satisfy requirements in SDWA Section 1445(g), to assemble and maintain a drinking water contaminant occurrence database for both regulated and unregulated contaminants in drinking water systems. NCOD houses data on unregulated contaminant occurrence; data from EPA's “Six-Year Review” of national drinking water regulations; and ambient and/or source water data. Section 1445(g)(3) of SDWA requires that EPA maintain UCMR data in the NCOD and use the data when evaluating the frequency and level of occurrence of contaminants in drinking water at a level of public health concern. UCMR results can be viewed by the public via NCOD ( https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/national-contaminant-occurrence-database-ncod ) or via the UCMR web page at: https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr.

B. What are the Consumer Confidence Reporting and Public Notice Reporting requirements for public water systems that are subject to UCMR?

In addition to reporting UCMR monitoring data to EPA, PWSs are responsible for presenting and addressing UCMR results in their annual Consumer Confidence Reports (CCRs) (40 CFR 141.153) and must address Public Notice (PN) requirements associated with UCMR (40 CFR 141.207). More details about the CCR and PN requirements can be viewed by the public at: https://www.epa.gov/ccr and https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/public-notification-rule, respectively.

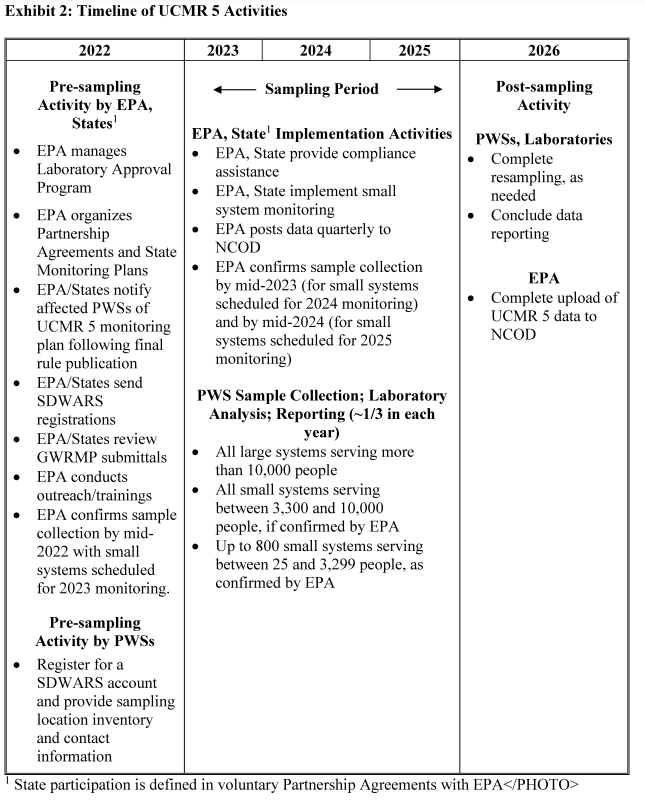

C. What is the UCMR 5 timeline?

This final rule identifies a UCMR 5 sampling period of 2023 to 2025. Prior to 2023 EPA will coordinate laboratory approval, tentatively select representative small systems (USEPA, 2021a), organize Partnership Agreements, develop State Monitoring Plans (see Section III.D of this preamble), establish monitoring schedules and inventory, and conduct outreach and training. Exhibit 2 of this preamble illustrates the major activities that EPA expects will take place in preparation for and during the implementation of UCMR 5.

BILLING CODE 6560-50-P

BILLING CODE 6560-50-C

D. What is the role of “States” in UCMR?

UCMR is a direct implementation rule ( i.e., EPA has primary responsibility for its implementation) and state participation is voluntary. Under the previous UCMR cycles, specific activities that individual states agreed to carry out or assist with were identified and established exclusively through Partnership Agreements. Through Partnership Agreements, states can help EPA implement UCMR and help ensure that the UCMR data are of the highest quality possible to best support the agency decision making. Under UCMR 5, EPA will continue to use the Partnership Agreement process to determine and document the following: The process for review and revision of the State Monitoring Plans; replacing and updating PWS information, including inventory ( i.e., PWS identification codes (PWSID), facility identification code along with associated facility types and water source type, etc.); review of proposed GWRMPs; notification and instructions for systems; and compliance assistance. EPA recognizes that states often have the best information about their PWSs and encourages them to partner in the UCMR 5 program.

E. How did EPA consider Children's Environmental Health?

By monitoring for unregulated contaminants that may pose health risks via drinking water, UCMR furthers the protection of public health for all citizens, including children. Children consume more water per unit of body weight compared to adults. Moreover, formula-fed infants drink a large amount of water compared to their body weight; thus, children's exposure to contaminants in drinking water may present a disproportionate health risk (USEPA, 2011). The objective of UCMR 5 is to collect nationally representative drinking water occurrence data on unregulated contaminants for future regulatory consideration. Information on the prioritization process, as well as contaminant-specific information ( e.g., source, use, production, release, persistence, mobility, health effects, and occurrence), that EPA used to select the analyte list, is contained in “Information Compendium for Contaminants for the Final Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5)” (USEPA, 2021e), available in the UCMR 5 public docket.

Since this is a final rule to monitor for contaminants and not to reduce their presence in drinking water to an acceptable level, the rule does not concern environmental health or safety risks presenting a disproportionate risk to children that would be addressed by this action (See Section V.G Executive Order 13045 of this preamble). Therefore, Executive Order 13045 does not apply to UCMR. However, EPA's Policy on Evaluating Health Risks to Children, which ensures that the health of infants and children is explicitly considered in the agency's decision making, is applicable, see: https://www.epa.gov/children/epas-policy-evaluating-risk-children.

EPA considered children's health risks during the development of UCMR 5. This included considering public comments about candidate contaminant priorities. Many commenters supported the agency's inclusion of PFAS and lithium in UCMR 5. Some commenters requested that EPA consider children and infant health risks in its risk communication for UCMR 5.

Using quantitation data from multiple laboratories, EPA establishes statistically-based UCMR reporting levels the agency considers feasible for the national network of approved drinking water laboratories. EPA generally sets the reporting levels as low as is technologically practical for measurement by that national network of laboratories, even if that level is well below concentrations that are currently associated with known or suspected health effects. In doing so, EPA positions itself to better address contaminant risk information in the future, including that associated with unique risks to children.

F. How did EPA address Environmental Justice (EJ)?

EPA has concluded that this action is not subject to Executive Order 12898 because it does not establish an environmental health or safety standard (see Section V.J Executive Order 12898 of this preamble). EPA Administrator Regan issued a directive to all EPA staff to incorporate environmental justice (EJ) into the agency's work, including regulatory activities, such as integrating EJ considerations into the regulatory development processes and considering regulatory options to maximize benefits to communities that “continue to suffer from disproportionately high pollution levels and the resulting adverse health and environmental impacts.” In keeping with this directive, and consistent with AWIA, EPA will, subject to the availability of sufficient appropriations, expand UCMR 5 to include all PWSs serving between 3,300 and 10,000 people as described in Sections I.A.4 and IV.B of this preamble. If there are sufficient appropriations, the expansion in the number of participating PWSs will provide a more comprehensive assessment of contaminant occurrence data from small and rural communities, including disadvantaged communities.

By developing a national characterization of unregulated contaminants that may pose health risks via drinking water from PWSs, UCMR furthers the protection of public health for all citizens. If EPA receives the needed appropriations, the expansion in monitoring scope reflected in UCMR 5 ( i.e., including all PWSs serving 3,300 to 10,000 people) will better support state and regional analyses and determination of potential EJ-related issues that need to be addressed. EPA structured the UCMR 5 rulemaking process to allow for meaningful involvement and transparency. EPA organized public meetings and webinars to share information regarding the development and implementation of UCMR 5; consulted with Tribal governments; and convened a workgroup that included representatives from several states. EPA will support stakeholder interest in UCMR 5 results by making them publicly available, as described in Section III.A of this preamble, and by developing additional risk-communication materials to help individuals and communities understand the significance of contaminant occurrence.

EPA received multiple comments on environmental justice considerations. Commenters expressed support for the continued collection of U.S. Postal Service Zip Codes for each PWS's service area and requested that EPA provide multilingual UCMR materials. EPA will continue to collect Zip Codes for UCMR 5, as collected under UCMR 3 and UCMR 4, to support potential assessments of whether or not certain communities are disproportionately impacted by particular drinking water contaminants. EPA also intends to develop the sampling instructions, fact sheets, and data summaries in both English and Spanish.

G. How did EPA coordinate with Indian Tribal Governments?

EPA has concluded that this action has Tribal implications. However, it will neither impose substantial direct compliance costs on federally recognized Tribal governments, nor preempt Tribal law. (See section V.F Executive Order 13175 of this preamble).

EPA consulted with Tribal officials under the EPA Policy on Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribes early in the process of developing this action to ensure meaningful and timely input into its development. EPA initiated the Tribal consultation and coordination process before proposing the rule by mailing a “Notification of Consultation and Coordination” letter on June 26, 2019, to the Tribal leadership of the then 573 federally recognized Tribes. The letter invited Tribal leaders and representatives of Tribal governments to participate in an August 6, 2019, UCMR 5 Tribal consultation and coordination informational meeting. Presentation topics included an overview of the UCMR program, potential approaches to monitoring and implementation for UCMR 5, and the UCMR 5 contaminants and analytical methods under consideration. After the presentation, EPA provided an opportunity for input and questions on the action. Eight representatives from five Tribes attended the August meeting. Tribal representatives asked clarifying questions regarding program costs to PWSs and changes in PWS participation per AWIA. EPA addressed the questions during the meeting. Following the meeting, EPA received and addressed one additional clarifying question from a Tribal representative during the Tribal consultation process. No other Tribal representatives submitted written comments during the UCMR 5 consultation comment period that ended September 1, 2019.

Prior to the August 2019 meeting, EPA provided additional opportunities for Tribal officials to provide meaningful and timely input into the development of the proposed rule. On July 10, 2019, EPA participated in a monthly conference call with the National Tribal Water Council (NTWC). EPA shared a brief summary of UCMR statutory requirements with the Council and highlighted the upcoming official Tribal meeting. EPA also invited Tribal leaders and representatives to participate in a public meeting, held on July 16, 2019, to discuss the development of the proposed rule. Representatives from six Tribes participated in the public meeting. Following the publication of the proposal, EPA advised the Indian Health Services of the 60-day public comment period to assist with facilitating additional Tribal comments on the proposed rule. EPA received no public comments from Tribal officials.

A complete summary of the consultation, titled, “Summary of the Tribal Coordination and Consultation Process for the Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) Proposal,” is provided in the UCMR 5 public docket listed in the ADDRESSES section of this preamble.

H. How are laboratories approved for UCMR 5 analyses?

Consistent with prior UCMRs, this action maintains the requirement that PWSs use laboratories approved by EPA to analyze UCMR 5 samples. Interested laboratories are encouraged to apply for EPA approval as early as possible. The UCMR 5 laboratory approval process, which began with the publication of the UCMR 5 proposal, is designed to assess whether laboratories possess the required equipment and can meet laboratory-performance and data-reporting criteria described in this action.

EPA expects demand for laboratory support to increase significantly based on the greater number of PWSs expected to participate in UCMR 5. EPA anticipates that the number of participating small water systems will increase from the typical 800 to approximately 6,000 (see Exhibit 5 in Section IV.B of this preamble). In preparation for this increase, EPA will solicit proposals and award contracts to laboratories to support small system monitoring prior to the end of the proficiency testing (PT) program. As in previous UCMR programs, EPA expects that laboratories awarded contracts by EPA will be required to first be approved to perform all methods. The requirements for the laboratory approval process are described in steps 1 through 6 of the following paragraphs.

EPA will require laboratories seeking approval to: (1) Provide EPA with data documenting an initial demonstration of capability (IDC) as outlined in each method; (2) verify successful performance at or below the minimum reporting levels (MRLs) as specified in this action; (3) provide information about laboratory standard operating procedures (SOPs); and (4) participate in two EPA PT studies for the analytes of interest. Audits of laboratories may be conducted by EPA prior to and/or following approval, and maintaining approval is contingent on timely and accurate reporting. The “UCMR 5 Laboratory Approval Manual” (USEPA, 2021f), available in the UCMR 5 public docket, provides more specific guidance on EPA laboratory approval program and the specific method acceptance criteria. EPA has included sample-collection procedures that are specific to the methods in the “UCMR 5 Laboratory Manual,” and will address these procedures in our outreach to the PWSs that will be collecting samples.

The UCMR 5 laboratory approval program will provide an assessment of the ability of laboratories to perform analyses using the methods listed in 40 CFR 141.40(a)(3), Table 1 of this preamble. Laboratory participation in the program is voluntary. However, as in the previous UCMRs, EPA will require PWSs to exclusively use laboratories that have been approved under the program. EPA will post a list of approved UCMR 5 laboratories to https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr and will bring this to the attention of the PWSs in our outreach.

1. Request To Participate

Laboratories interested in the UCMR 5 laboratory approval program first email EPA at: UCMR_Lab_Approval@epa.gov to request registration materials. EPA began accepting requests beginning with the publication of the proposal in the Federal Register .

2. Registration

Laboratory applicants provide registration information that includes laboratory name, mailing address, shipping address, contact name, phone number, email address, and a list of the UCMR 5 methods for which the laboratory is seeking approval. This registration step provides EPA with the necessary contact information and ensures that each laboratory receives a customized application package.

3. Application Package

Laboratory applicants will complete and return a customized application package that includes the following: IDC data, including precision, accuracy, and results of MRL studies; information regarding analytical equipment and other materials; proof of current drinking water laboratory certification (for select compliance monitoring methods); method-specific SOPs; and example chromatograms for each method under review.

As a condition of receiving and maintaining approval, the laboratory must promptly post UCMR 5 monitoring results and quality control data that meet method criteria (on behalf of its PWS clients) to EPA's UCMR electronic data reporting system, SDWARS.

Based on the January 1, 2023 start for UCMR 5 sample collection, the deadline for a laboratory to submit the necessary registration and application information is August 1, 2022.

4. EPA's Review of Application Package

EPA will review the application packages and, if necessary, request follow-up information. Laboratories that successfully complete the application process become eligible to participate in the UCMR 5 PT program.

5. Proficiency Testing

A PT sample is a synthetic sample containing a concentration of an analyte or mixture of analytes that is known to EPA, but unknown to the laboratory. To be approved, a laboratory must meet specific acceptance criteria for the analysis of a UCMR 5 PT sample(s) for each analyte in each method, for which the laboratory is seeking approval. EPA offered three PT studies between publication of the proposed rule and final rule, and anticipates offering at least two additional studies. Interested laboratories must participate in and report data for at least two PT studies. This allows EPA to collect a robust dataset for PT results, and provides laboratories with extra analytical experience using UCMR 5 methods. Laboratories must pass a PT for every analyte in the method to be approved for that method and may participate in multiple PT studies in order to produce passing results for each analyte. EPA has taken this approach in UCMR 5, recognizing that EPA Method 533 contains 25 analytes. EPA does not expect to conduct additional PT studies after the start of PWS monitoring; however, EPA expects to conduct laboratory audits (remote and/or on-site) throughout the implementation of UCMR 5 on an as needed and/or random basis. Initial laboratory approval is contingent on successful completion of PT studies, which includes properly uploading the PT results to SDWARS. Continued laboratory approval is contingent on successful completion of the audit process and satisfactorily meeting all the other stated conditions.

6. Written EPA Approval

For laboratories that have already successfully completed steps 1 through 5, EPA sent the laboratory a notification letter listing the methods for which approval was “pending” ( i.e., pending promulgation of this final rule). Because no changes have been made to the final rule that impact the laboratory approval program, laboratories that received pending-approval letters will be notified of full approval without further action on their part. Approval actions for additional laboratories that successfully complete steps 1 through 5 will also be documented by EPA in writing.

I. What documents are being incorporated by reference?

The following methods are being incorporated by reference into this section for UCMR 5 monitoring. All method material is available for inspection electronically at https://www.regulations.gov (Docket ID No. EPA-HQ-OW-2020-0530), or from the sources listed for each method. The methods that may be used to support monitoring under this final rule are as follows:

1. Methods From the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

The following methods are available at EPA's Docket No. EPA-HQ-OW-2020-0530.

(i) EPA Method 200.7 “Determination of Metals and Trace Elements in Water and Wastes by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectrometry,” Revision 4.4, 1994. Available at https://www.epa.gov/esam/method-2007-determination-metals-and-trace-elements-water-and-wastes-inductively-coupled-plasma. This is an EPA method for the analysis of metals and trace elements in water by ICP-AES and may be used to measure lithium during UCMR 5. See also the discussion of non-EPA alternative methods for lithium in this section.

(ii) EPA Method 533 “Determination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Drinking Water by Isotope Dilution Anion Exchange Solid Phase Extraction and Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry,” November 2019, EPA 815-B-19-020. Available at https://www.epa.gov/dwanalyticalmethods/analytical-methods-developed-epa-analysis-unregulated-contaminants. This is an EPA method for the analysis PFAS in drinking water using SPE and LC/MS/MS and is to be used to measure 25 PFAS during UCMR 5 (11Cl-PF3OUdS, 8:2 FTS, 4:2 FTS, 6:2 FTS, ADONA, 9Cl-PF3ONS, HFPO-DA (GenX), NFDHA, PFEESA, PFMPA, PFMBA, PFBS, PFBA, PFDA, PFDoA, PFHpS, PFHpA, PFHxS, PFHxA, PFNA, PFOS, PFOA, PFPeS, PFPeA, and PFUnA).

(iii) EPA Method 537.1 “Determination of Selected Per- and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substances in Drinking Water by Solid Phase Extraction and Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS/MS),” Version 2.0, March 2020, EPA/600/R-20/006. Available at https://www.epa.gov/dwanalyticalmethods/analytical-methods-developed-epa-analysis-unregulated-contaminants. This is an EPA method for the analysis of PFAS in drinking water using SPE and LC/MS/MS and is to be used to measure four PFAS during UCMR 5 (NEtFOSAA, NMeFOSAA, PFTA, and PFTrDA).

2. Alternative Methods From American Public Health Association—Standard Methods (SM)

The following methods are from American Public Health—Standard Methods (SM), 800 I Street NW, Washington, DC 20001-3710.

(i) “Standard Methods for the Examination of Water & Wastewater,” 23rd edition (2017).

(a) SM 3120 B, “Metals by Plasma Emission Spectroscopy (2017): Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Method.” This is a Standard Method for the analysis of metals in water and wastewater by emission spectroscopy using ICP and may be used for the analysis of lithium.

(ii) “Standard Methods Online,” approved 1999. Available for purchase at https://www.standardmethods.org.

(a) SM 3120 B, “Metals by Plasma Emission Spectroscopy: Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Method, Standard Methods Online,” revised December 14, 2020. This is a Standard Method for the analysis of metals in water and wastewater by emission spectroscopy using ICP and may be used for the analysis of lithium.

3. Methods From ASTM International

The following methods are from ASTM International, 100 Barr Harbor Drive, West Conshohocken, PA 19428-2959.

(i) ASTM D1976-20, “Standard Test Method for Elements in Water by Inductively-Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy,” approved May 1, 2020. Available for purchase at https://www.astm.org/Standards/D1976.htm. This is an ASTM method for the analysis of elements in water by ICP-AES and may be used to measure lithium.

IV. Description of Final Rule and Summary of Responses to Public Comments

EPA published “Revisions to the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) for Public Water Systems and Announcement of Public Meeting;” Proposed Rule, on March 11, 2021 (86 FR 13846, (USEPA, 2021g)). The UCMR 5 proposal identified three EPA analytical methods, and multiple alternative methods, to support water system monitoring for 30 UCMR 5 contaminants (29 PFAS and lithium) and detailed other potential changes relative to UCMR 4. Among the other changes reflected in the UCMR 5 proposal were the following: Requirement for water systems serving 3,300 to 10,000 people to monitor per AWIA requirements “subject to the availability of appropriations”; provisions for sampling frequency, timing, and locations; submission timeframe for GWRMPs; data reporting timeframes; and reporting requirements.

EPA received 75 sets of comments from 72 public commenters, including other federal agencies, state and local governments, utilities and utility stakeholder organizations, laboratories, academia, non-governmental organizations, and other interested stakeholders. After considering the comments, EPA developed the final UCMR 5 as described in Exhibit 3 of this preamble. Except as noted, the UCMR 5 final rule approach is consistent with the proposed rule. A track-changes version of the rule language, comparing UCMR 4 to UCMR 5, (“Revisions to 40 CFR 141.35 and 141.40” (USEPA, 2021h)), is included in the electronic docket listed in the ADDRESSES section of this preamble.

This section summarizes key aspects of this final rule and the associated comments received in response to the proposed rule. EPA has compiled all public comments and EPA's responses in the “Response to Comments on the Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) Proposal,” (USEPA, 2021i), which can be found in the electronic docket listed in the ADDRESSES section of this preamble.

| Number | Title | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CFR rule section | Description of section | Corresponding preamble section | |

| Number | Title | ||

| 40 CFR 141.40(a)(3) | Contaminants in UCMR 5 | Maintains proposed list of 29 PFAS and lithium for monitoring | IV.A |

| 40 CFR 141.35(d), 40 CFR 141.40(a)(2)(ii), and 40 CFR 141.40(a)(4)(ii) | Scope of UCMR 5 applicability | Revises the scope of UCMR 5 to reflect that small CWSs and NTNCWSs serving 25 to 10,000 people will monitor (consistent with AWIA), if they are notified by the agency | IV.B |

| 40 CFR 141.40(a)(i)(B) | Sampling frequency and timing | Maintains proposed sample frequency (four sample events for SW, two sample events for GW) | IV.C |

| 40 CFR 141.35(c)(3) | Sampling locations and Ground Water Representative Monitoring Plans (GWRMPs) | Maintains proposed flexibility for PWSs to submit a GWRMP proposal to EPA | IV.D |

| 40 CFR 141.35(c)(6)(ii) and 40 CFR 141.40(a)(5)(vi) | Reporting timeframe | Maintains proposed timeframe (“within 90 days from the sample collection date”) for laboratories to post and approve analytical results in EPA's electronic data reporting system (for review by the PWS). Maintains proposed timeframe (“30 days from when the laboratory posts the data to EPA's electronic data reporting system”) for PWSs to review, approve, and submit data to the state and EPA | IV.E |

| 40 CFR 141.35(e) | Reporting requirements | Removes one proposed data element, maintains 27 proposed data elements, and clarifies the use of state data | IV.F |

| 40 CFR 141.40(a)(3) | Minimum reporting levels (MRL) | Maintains proposed MRLs for contaminants | IV.G |

A. What contaminants must be monitored under UCMR 5?

1. This Final Rule

EPA is maintaining the proposed list of UCMR 5 contaminants and the methods associated with analyzing those contaminants (see Exhibit 4 of this preamble). Further information on the prioritization process, as well as contaminant-specific information ( e.g., source, use, production, release, persistence, mobility, health effects, and occurrence), that EPA used to select the analyte list, is contained in “Information Compendium for Contaminants for the Final Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5)” (USEPA, 2021e). This Information Compendium can be found in the electronic docket listed in the ADDRESSES section of this preamble.

| 1 EPA Method 533 (Solid phase extraction (SPE) liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS)) (USEPA, 2019b). | |

| 2 EPA Method 537.1 Version 2.0 (Solid phase extraction (SPE) liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS)) (USEPA, 2020). | |

| 3 EPA Method 200.7 (Inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES)) (USEPA, 1994). | |

| 4 Standard Methods (SM) 3120 B (SM, 2017) or SM 3120 B-99 (SM Online, 1999). | |

| 5 ASTM International (ASTM) D1976-20 (ASTM, 2020). | |

| Twenty-five Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) using EPA Method 533 (SPE LC/MS/MS): | |

| 11-chloroeicosafluoro-3-oxaundecane-1-sulfonic acid (11Cl-PF3OUdS) | perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA). |

| 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H-perfluorodecane sulfonic acid (8:2 FTS) | perfluorododecanoic acid (PFDoA). |

| 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H-perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (4:2 FTS) | perfluoroheptanesulfonic acid (PFHpS). |

| 1H, 1H, 2H, 2H-perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (6:2 FTS) | perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA). |

| 4,8-dioxa-3H-perfluorononanoic acid (ADONA) | perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS). |

| 9-chlorohexadecafluoro-3-oxanone-1-sulfonic acid (9Cl-PF3ONS) | perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA). |

| hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA) (GenX) | perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA). |

| nonafluoro‐3,6‐dioxaheptanoic acid (NFDHA) | perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). |

| perfluoro (2‐ethoxyethane) sulfonic acid (PFEESA) | perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). |

| perfluoro‐3‐methoxypropanoic acid (PFMPA) | perfluoropentanesulfonic acid (PFPeS). |

| perfluoro‐4‐methoxybutanoic acid (PFMBA) | perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA). |

| perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS) | perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUnA). |

| perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) | |

| Four Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) using EPA Method 537.1 (SPE LC/MS/MS): | |

| n-ethyl perfluorooctanesulfonamidoacetic acid (NEtFOSAA) | perfluorotetradecanoic acid (PFTA). |

| n-methyl perfluorooctanesulfonamidoacetic acid (NMeFOSAA) | perfluorotridecanoic acid (PFTrDA). |

| One Metal/Pharmaceutical using EPA Method 200.7 (ICP-AES) or alternate SM or ASTM: | |

| lithium | |

2. Summary of Major Comments and EPA Responses

Those who expressed an opinion about the proposed UCMR 5 analytes were supportive of EPA's inclusion of the 29 PFAS and lithium. Commenters expressed mixed opinions on the consideration of additional contaminants, particularly “aggregate PFAS,” Legionella pneumophilia, haloacetonitriles, and 1,2,3-trichloropropane. The major comments and EPA responses regarding these contaminants are summarized in the discussion that follows.

a. Aggregate PFAS Measure

EPA received multiple comments encouraging the agency to validate and include a total organic fluorine (TOF) and/or total oxidizable precursors (TOP) technique in UCMR 5 as a screening tool to determine “total PFAS.” EPA also received comments expressing concern for the limitations of the analytical methodologies, including a lack of sensitivity and specificity for PFAS using TOF.

EPA has not identified a complete, validated, peer-reviewed aggregate PFAS method with the appropriate specificity and sensitivity to support UCMR 5 monitoring. EPA's Office of Water and Office of Research and Development are currently developing and evaluating methodologies for broader PFAS analysis in drinking water, however, the measurement approaches are subject to significant technical challenges. The sensitivity of TOF is currently in the low μg/L range, as opposed to the low ng/L range of interest required for PFAS analysis in drinking water. TOF is also not specific to PFAS. TOP, while focusing on PFAS, is limited to measuring compounds that can be detected by LC/MS/MS and the technique requires two LC/MS/MS analyses; one before oxidation and one after oxidation. EPA is evaluating the TOP approach to understand the degree to which certain precursors are oxidized, and subsequently measurable by LC/MS/MS, as well as the degree to which PFAS that were measured in the pre-oxidation sample are still measured post-oxidation.

EPA is also monitoring progress by commercial laboratories and academia. In 2020 and 2021, EPA contacted commercial laboratories that advertised TOF capability, and these laboratories indicated that they had not yet commercialized the TOF method (see Appendix 4 in “Response to Comments on the Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) Proposal,” (USEPA, 2021i), which can be found in the electronic docket listed in the ADDRESSES section of this preamble). TOP has been more widely commercialized but is often used as an exploratory tool to estimate precursors.

In summary, there are still analytical challenges leading to uncertainties in the results using the TOF and TOP techniques. More research and method refinement are needed before a peer-reviewed validated method that meets UCMR quality control needs is available to address PFAS more broadly.

b. Legionella Pneumophila

Some comments supported EPA's proposal to not include Legionella pneumophila in UCMR 5, while others encouraged EPA to add it. EPA has decided not to include Legionella pneumophila in the final UCMR 5.

Under EPA's Surface Water Treatment Rule (SWTR), EPA established NPDWRs for Giardia, viruses, Legionella, turbidity and heterotrophic bacteria and set maximum contaminant level goals of zero for Giardia lamblia, viruses and Legionella pneumophila (54 FR 27486, June 29, 1989 (USEPA, 1989)). EPA is currently examining opportunities to enhance protection against Legionella pneumophila through revisions to the suite of Microbial and Disinfection Byproduct (MDBP) rules. In addition to the SWTR, the MDBP suite includes the Stage 1 and Stage 2 Disinfectants and Disinfection Byproduct Rules; the Interim Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule; and the Long Term 1 Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule.

As stated in the conclusions from EPA's third “Six-Year Review of Drinking Water Standards” (82 FR 3518, January 11, 2017 (USEPA, 2017)), “EPA identified the following NPDWRs under the SWTR as candidates for revision, because of the opportunity to further reduce residual risk from pathogens (including opportunistic pathogens such as Legionella ) beyond the risk addressed by the current SWTR.” In accordance with the dates in the Settlement Agreement between EPA and Waterkeeper Alliance ( Waterkeeper Alliance, Inc. v. U.S. EPA, No. 1:19-cv-00899-LJL (S.D.N.Y. Jun. 1, 2020)), the agency anticipates signing a proposal for revisions to the MDBP rules and a final action on the proposal by July 31, 2024 and September 30, 2027, respectively. EPA has concluded that UCMR 5 data collection for Legionella pneumophila would not be completed in time to meaningfully inform MDBP revision and that UCMR 5 data for Legionella pneumophila would soon lack significance because it would not reflect conditions in water systems after any regulatory revisions become effective (because water quality would be expected to change as a result of PWSs complying with such regulatory revisions).

EPA estimates that Legionella pneumophila monitoring under UCMR 5 would have added $10.5 million in new expenses for large PWSs, $20 million in new expenses for the agency for small system monitoring, and $0.5 million in new expenses for small PWSs and states over the 5-year UCMR period. Because the data would not be available in time to inform MDBP regulatory revisions and because MDBP revisions could change the presence of Legionella pneumophila in drinking water distribution systems ( Legionella occurrence may change, for example, if the required minimum disinfectant residual concentration is higher following MDBP revisions), EPA concluded that the expense of this monitoring is not warranted given the limited utility of the data.

c. Haloacetonitriles

Some commenters agreed with EPA's rationale for not including the four unregulated haloacetonitrile disinfection byproducts (DBPs) in UCMR 5, while others encouraged EPA to include them. EPA has decided not to include haloacetonitrile DBPs in the final UCMR 5.

As was the case with Legionella pneumophila, EPA has concluded that UCMR 5 data collection for haloacetonitriles would not be completed in time to meaningfully inform MDBP revision and that UCMR 5 data would not reflect conditions in water systems after any regulatory revisions become effective (haloacetonitrile occurrence may change, for example, if the required minimum disinfectant residual concentration is higher following MDBP revisions).

As with Legionella pneumophila, inclusion of haloacetonitriles in UCMR 5 would introduce significant monitoring and reporting complexity and cost compared to the sampling design for PFAS and lithium. If haloacetonitriles were to be added to UCMR 5, most of the additional expenses would be borne by large PWSs (for analysis of their samples) and EPA (for analysis of samples from small PWSs). EPA estimates this would result in $13 million in new expenses for large PWSs, $19 million in new expenses for the agency, and $0.5 million in new expenses for small PWSs and states over the 5-year UCMR period.

Because the data would not be available in time to inform MDBP regulatory revisions and because MDBP revisions could change the presence of haloacetonitriles in drinking water distribution systems, EPA concluded that the expense of this monitoring is not warranted given the limited utility of the data.

d. 1,2,3-Trichloropropane

EPA received some comments that support the agency's proposed decision to not include 1,2,3-trichloropropane (1,2,3-TCP) monitoring in UCMR 5, and others recommending that 1,2,3-TCP be included. EPA concluded that appropriate analytical methods are not currently available to support additional UCMR data collection ( i.e., above and beyond the data collection under UCMR 3 (USEPA, 2019c)).

Several commenters suggested that EPA consider analytical methods to monitor for 1,2,3-trichloropropane at lower levels. They suggested, for example, that the agency use California method SRL-524M (California DHS, 2002), which is prescribed by the state for compliance monitoring at 0.005 μg/L (5 ng/L). EPA has reviewed SRL 524M and determined that the associated quality control (QC) and IDC criteria do not meet the EPA's needs for drinking water analysis. See also EPA's “Response to Comments on the Fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) Proposal,” (USEPA, 2021i), which can be found in the electronic docket listed in the ADDRESSES section of this preamble.

Occurrence data collected during UCMR 3 (77 FR 26072, May 2, 2012 (USEPA, 2012)) for 1,2,3-trichloropropane may be found at https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr/occurrence-data-unregulated-contaminant-monitoring-rule#3.

B. What is the UCMR 5 sampling design?

1. This Final Rule

EPA has utilized up to three different tiers of contaminant monitoring, associated with three different “lists” of contaminants, in past UCMRs. EPA designed the monitoring tiers to reflect the availability and complexity of analytical methods, laboratory capacity, sampling frequency, and cost. The Assessment Monitoring tier is the largest in scope and is used to collect data to determine the national occurrence of “List 1” contaminants for the purpose of estimating national population exposure. Assessment Monitoring has been used in the four previous UCMRs to collect occurrence data from all systems serving more than 10,000 people and a representative sample of 800 smaller systems. Consistent with AWIA, the Assessment Monitoring approach was redesigned for UCMR 5 and reflects the plan, subject to additional appropriations being made available for this purpose, that would require all systems serving 3,300 or more people and a representative sample of systems serving 25 to 3,299 people to perform monitoring (USEPA, 2021a). The population-weighted sampling design for the nationally representative sample of small systems (used in previous UCMR cycles to select 800 systems serving 25 to 10,000 people and used in UCMR 5 to select 800 systems serving 25 to 3,299 people) calls for the sample to be stratified by water source type (ground water or surface water), service size category, and state (where each state is allocated a minimum of two systems in its State Monitoring Plan). The allowable margin of error at the 99 percent confidence level is ±1 percent for an expected contaminant occurrence of 1 percent at the national level. Assessment Monitoring is the primary tier used for contaminants and generally relies on analytical methods that use more common techniques that are expected to be widely available. EPA has used an Assessment Monitoring tier for 72 contaminants and contaminant groups over the course of UCMR 1 through UCMR 4. The agency is exclusively requiring Assessment Monitoring in UCMR 5. This monitoring approach yields the most complete set of occurrence data to support EPA's decision making.

2. Summary of Major Comments and EPA Responses

Many commenters expressed support for the increase in small system Assessment Monitoring, with no opposition to the inclusion of all PWSs serving 3,300 to 10,000 people in UCMR 5. The U.S. Small Business Administration asked that EPA clarify small-system responsibilities in the event of inadequate EPA funding to fully support the envisioned monitoring.

Recognizing the uncertainty in funding from year-to-year, the agency will implement a “monitor if notified” approach for PWSs serving 25 to 10,000 people. In 2022, EPA will notify the approximately 6,000 small PWSs tentatively selected for the expanded UCMR 5 (all PWSs serving 3,300 to 10,000 people and a statistically-based, nationally representative set of 800 PWSs serving 25 to 3,299 people) of their anticipated UCMR 5 monitoring requirements; that initial notification will specify that monitoring is conditioned on EPA having sufficient funds and will be confirmed in a second notification. Upon receiving appropriations for a particular year, EPA will determine the number of small PWSs whose monitoring is covered by the appropriations, and notify the included small PWSs of their upcoming requirements at least six months prior to their scheduled monitoring. EPA has made minor edits to 40 CFR 141.35 and 40 CFR 141.40 for consistency with this approach.

Additionally, to ensure that EPA has access to a nationally representative set of small-system data, even in the absence of sufficient appropriations to support the planned monitoring by small systems, a statistically-based nationally representative set of 800 PWSs will also be selected from among the PWSs serving 25 to 10,000 people. An updated description of the statistical approach for the nationally representative samples for UCMR 5 is available in the docket as “Selection of Nationally Representative Public Water Systems for the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule: 2021 Update” (USEPA 2021a).

To minimize the impact of the final rule on small systems (those serving 25 to 10,000 people), EPA pays for their sample kit preparation, sample shipping fees, and sample analysis. Large systems (those serving more than 10,000 people) pay for all costs associated with their monitoring. Exhibit 5 of this preamble shows a summary of the estimated number of PWSs subject to monitoring.

| List 1 chemicals | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 EPA pays for all analytical costs associated with monitoring at small systems. | ||

| 2 Counts for small PWSs serving 3,300-10,000 people are approximate. | ||

| 3 Large system counts are approximate. | ||

| 4 In the absence of appropriations to support monitoring at all PWSs serving 3,300 to 10,000 people, EPA could instead include as few as 400 PWSs serving 25 to 3,299 people and 400 PWSs serving 3,300 to 10,000 people (for a representative sample of 800 PWSs serving 25 to 10,000 people). | ||

| System size (number of people served) | National sample: Assessment monitoring design | Total number of systems per size category |

| List 1 chemicals | ||

| Small Systems 1 (25-3,299) | 800 randomly selected systems (CWSs and NTNCWSs) | 4 800 |

| Small Systems 1 2 (3,300-10,000) | All systems (CWSs and NTNCWSs) subject to the availability of appropriations | 4 5,147 |

| Large Systems 3 (10,001 and over) | All systems (CWSs and NTNCWSs) | 4,364 |

| Total | 10,311 | |

C. What is the sampling frequency and timing?

1. This Final Rule