Oil spill prevention is about keeping oil spills (technically called oil discharges) from damaging the environment. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations address an onshore or offshore facility's preparedness and its ability to prevent, control, and respond to an oil discharge. Additionally, EPA strives to limit the damage done by oil spills through regulations requiring the immediate notification of a discharge of a harmful quantity of oil. In the event of an oil discharge, EPA prefers to have responsible parties finance the cleanup of the parties’ own oil discharges. When the responsible party is unknown or refuses to pay, the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund may cover removal costs and/or damages that are not recovered from a responsible party.

Overview

- Oil spills are a danger to public health, our natural resources, and the economy. Therefore, a number of laws and regulations were created to prevent and mitigate harm from oil spills.

- Oil is often stored and transported in large quantities, posing a risk for spills.

- Non-petroleum oils, such as vegetable oils and animal fats, can also pose similar threats to those caused by petroleum products.

Oil spills endanger public health, imperil drinking water, devastate natural resources, and disrupt the economy. In fact, a single pint of oil released into the water can cover one acre of water surface area and seriously damage an aquatic habitat. Birds, fish, and other wildlife can lose necessary food sources and habitat. Populations that depend on marine resources as part of their traditional subsistence culture also can be drastically affected. That means every effort must be made to prevent oil spills and to clean them up promptly once they occur.

Vast quantities of oil pose a risk

In an increasingly technological era, the U.S. has become more dependent upon oil-based products to help maintain our high standard of living. Products derived from petroleum, such as heating oil and gasoline, provide fuel for our automobiles, heat for our homes, and energy for the machinery used in our industries. Other products derived from petroleum, including plastics and pharmaceuticals, provide us with convenience and help to make our lives more comfortable.

Additionally, non-petroleum oils, such as vegetable oils and animal fats, are increasingly being consumed in the U.S. These oils can contain toxic components and can produce physical effects that are similar to petroleum oils. That means spills of non-petroleum oils also pose threats to public health and the environment.

Because we use vast quantities of oils, they are usually stored and transported in large volumes. During storage or transport, and occasionally as the result of exploration activities, oils and other oil-based products are sometimes spilled, reaching our waterways. When this occurs, human health, environmental quality, and economic prosperity are put at risk.

Laws and regulations

Since the 1970s, Congress has enacted several laws mandating oil pollution prevention efforts. These laws called on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to issue regulations for the prevention of oil spills into navigable waters and adjoining shorelines of the U.S.

Despite the implementation of these regulations and other federal pollution prevention requirements, problems with oil spills continued to increase, culminating in a devastating oil discharge into Alaska’s Prince William Sound in 1989 from an ocean vessel. Further laws and regulations followed to provide a basic framework for operational procedures, containment requirements, spill planning and response needs of certain facilities that might release oil into navigable waters and adjoining shorelines.

Some facilities are required to submit response plans designed to ensure that sufficient personnel and equipment are available to respond to and mitigate a worst-case oil discharge.

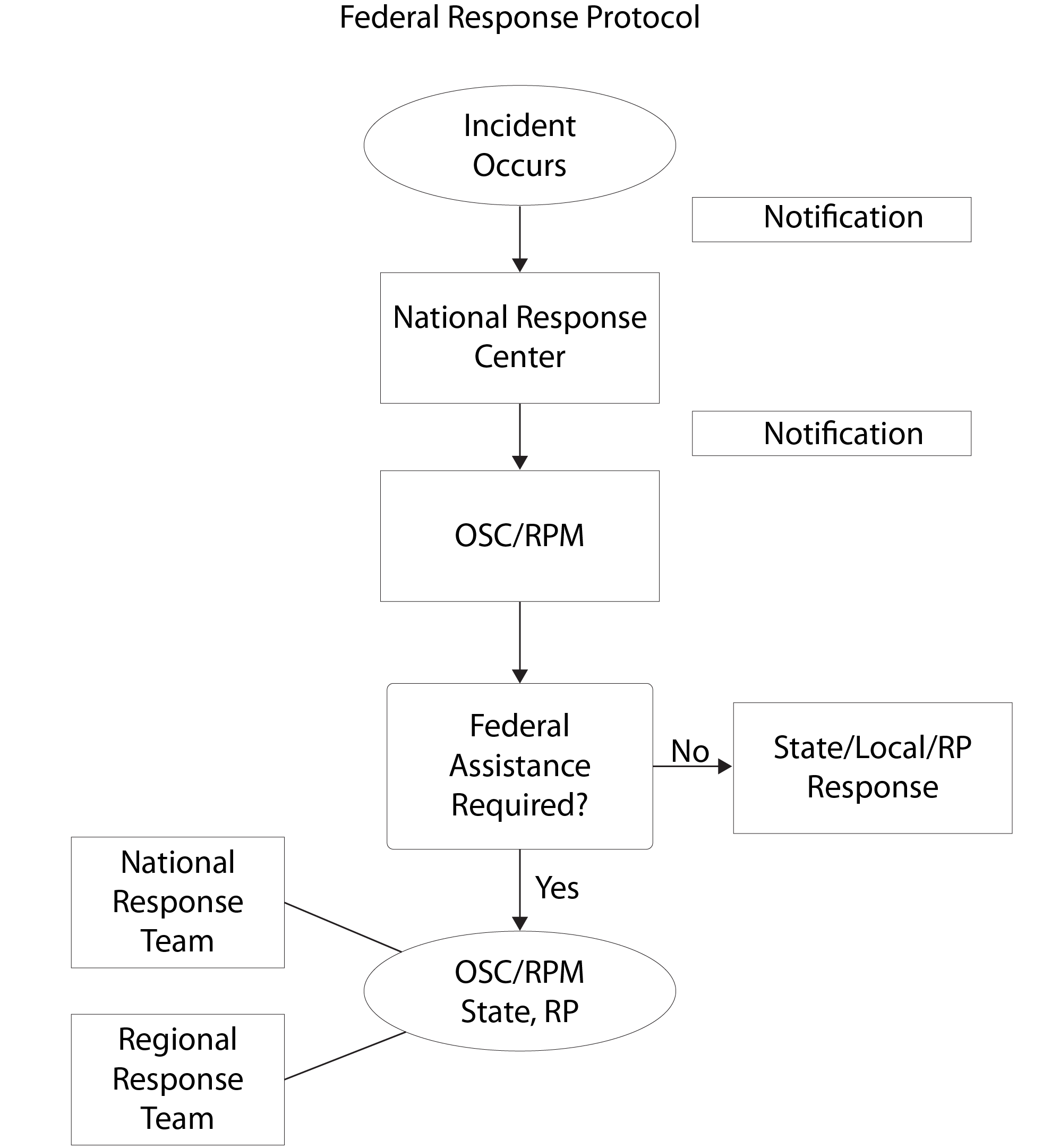

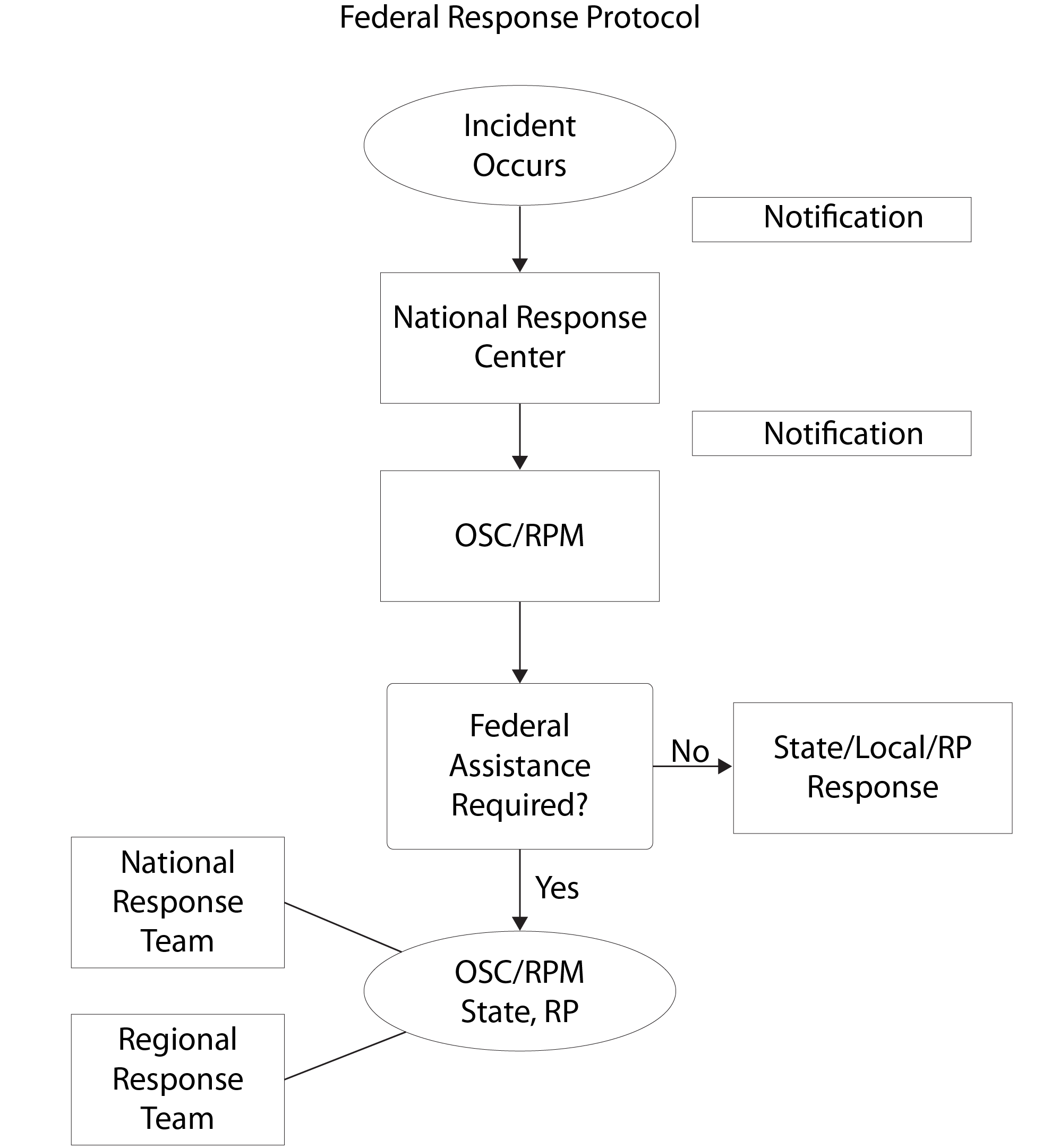

Aside from facility-specific requirements to mitigate oil spills, the federal government has established a coordinated network of officials to respond to oil spills by providing technical support and response equipment, as needed. Reportable releases of oil into navigable waters and adjoining shorelines must be reported to the National Response Center, at which time federal authorities will determine the appropriate response.

What is not covered in this subject?

- This subject focuses on the oil spill prevention regulations under the jurisdiction of the EPA.

This Oil Spill Prevention subject focuses on Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-jurisdictional oil spill prevention. It does not attempt to cover:

- Transportation-related onshore facilities, deepwater ports, and vessels when they fall under Department of Transportation jurisdiction.

- Requirements specific to offshore facilities, including associated pipelines, regulated by the Department of Interior.

- Container and tank requirements under EPA regulations dedicated to non-oil hazardous substance spills or storage, emergency planning and community right-to-know, chemical accident prevention, stormwater, pesticides, hazardous wastes, used oil management, underground storage tanks, wastewater pretreatment, effluents, or PCBs.

- Container and tank requirements under the jurisdiction of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) or the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA).

- Container and tank provisions under National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards or the International Fire Code (IFC).

Historical notes

- Several notable oil spill disasters in recent history led to the creation of new agencies and regulations designed to reduce environmental damage from the production, transport and storage of oil.

Water pollution is not a new phenomenon. It is likely our ancestors in the Middle Ages had water pollution with human and animal waste and ordinary garbage. However, in recent history industrialized areas experienced a new kind of water pollution — oil spills from onshore or offshore facilities. Several oil spill disasters have shaped U.S. laws and regulations for oil spill prevention. Four of them are covered here.

1969 Cuyahoga River fire in Ohio

What makes the Cuyahoga River fire so infamous is that the river became so polluted that the water erupted into flames. The first known fire occurred in 1936, when a spark from a blowtorch ignited floating debris and oils. Over the next 30 years, the river caught fire several more times.

In 1969, another major fire erupted, but this time, the national news media covered the story, and this prompted the nation to take action against water pollution. The overwhelming public response to the fire, in part, helped create the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 and motivated Congress, in 1972, to amend the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA) to make it unlawful for anyone to discharge any pollutant, including oil, into navigable waters, unless a permit was obtained. This amended law became known as the Clean Water Act (CWA) we know today.

1988 Monongahela River diesel tank release in Pennsylvania

In January 1988, the shell plates of a reconstructed four-million-gallon aboveground storage tank in Floreffe, Pennsylvania, experienced a “brittle fracture” failure. Brittle fracture is a type of structural failure in aboveground steel tanks, characterized by rapid crack formation that can cause sudden tank failure. The tank split apart while being filled to capacity for the first time after it had been dismantled and moved from an Ohio location and reassembled at the Floreffe facility. After splitting, the tank collapsed and discharged approximately 3.8 million U.S. gallons of diesel fuel. Of this amount, approximately 750,000 U.S. gallons were discharged into the Monongahela River. The spill temporarily contaminated drinking water sources, damaged the ecosystems of the Monongahela and Ohio Rivers, and negatively affected private property and local businesses. The spill highlights the direct impact inland spills can have on large populations — in this case, one million people were affected.

1989 Prince William Sound oil spill in Valdez, Alaska

On March 24, 1989, a fully loaded oil tanker grounded and ruptured, spilling 11 million gallons of crude oil in Alaska’s Prince William Sound, an environmentally sensitive area. It turns out underwater rocks tore huge holes in eight of the vessel’s 11 giant cargo holds. Seven hours after the spill was reported, the resulting oil slick was 1,000 feet wide and four miles long. The spill made national headlines, and in response to the new public awareness of the damaging effects of major oil spills, Congress unanimously enacted tougher oil spill legislation. On August 18, 1990, the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA) was signed into law.

1991 butter spill in Madison, Wisconsin

Not all oil spills involve petroleum oil. Animal fats and vegetable oils can also cause great harm to the environment when spilled. The butter spill described here demonstrates that oil spills can come from many different sources and that fires and other incidents can lead to spills. A fire broke out at a refrigerated warehousing facility in Madison, Wisconsin, in May 1991. The fire destroyed roughly 50 million pounds of food, including nearly 16 million pounds of butter. When the fire reached the butter and animal tallow in the warehouse, it became a hard-to-control grease fire. Melted butter spilled into roadways and ditches, threatening the environment and making it more difficult to fight the fire.

Six truckloads of sand were applied to the butter spill in an attempt to absorb it and prevent it from reaching Starkweather Creek. Engineers dug a channel from the warehouse to a low-lying area beneath a highway overpass and built hundreds of feet of redirecting dikes to allow the melted butter to flow into the depression and other lagoons. Very few contaminants were reported to have reached the creek. It was hypothesized that, had the butter been able to reach the creek, the resulting loss of oxygen in the water would have affected the resident fish species and reversed the effects of a recent $1 million cleanup effort in the area’s watershed.

Related federal laws and regulations

- Federal laws give EPA the authority to issue regulations relating to oil spills and spill prevention.

Several laws give the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority to issue regulations pertaining to oil spills and oil spill prevention. Together, the laws and regulations laid out here work to protect the environment from oil discharges.

Rivers and Harbors Act

The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 was intended to protect the navigability of commercial waters.

Federal Water Pollution Control Act

- The FWPCA provided the first funds for constructing the public works that treat municipal wastewater before it is discharged into the environment. It was later amended to create the first Clean Water Act.

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA) was enacted in 1948 and provided the first funds for constructing publicly owned treatment works (POTWs) that treat municipal wastewater prior to its discharge into the environment.

The FWPCA was amended on April 3, 1970, by the Water Quality Improvement Act (WQIA) of 1970 (under Public Law 91-224). The WQIA amended the prohibitions on discharges of oil to allow such discharges only when consistent with regulations to be issued by the President and where permitted by Article IV of the 1954 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil (see 33 U.S.C. 1321).

In issuing regulations, the President was authorized to determine quantities of oil which would be harmful to the public health or welfare of the U.S., including, but not limited to, fish, shellfish, and wildlife, as well as public and private property, shorelines, and beaches.

Water Quality Act

The Water Quality Act of 1965 established interstate water quality standards, requiring that each water body achieve or maintain specific water quality standards.

Clean Water Act

- The Clean Water Act is the principal federal statute that protects navigable waters and adjoining shorelines from pollution.

When water is so polluted it can catch fire, the public and national news media will notice. The overwhelming public response to a Cuyahoga River fire in Cleveland in June 1969 prompted Congress to enact the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA) of 1972, as amended.

The law became better known as the Clean Water Act (CWA), and the CWA is the principal federal statute for protecting navigable waters, adjoining shorelines, and the waters of the contiguous zone from pollution, including oil spills. It established a technology-based approach to maintaining water quality.

The Act prohibits discharges without a permit and allows permitted discharges to release only limited amounts of chemicals into navigable waters. As a result of the CWA, most point source discharges were successfully controlled, and the quality of the nation’s waters generally remained stable or improved slightly. The CWA sets the framework for a comprehensive program for water pollution control. The major objectives of the CWA include eliminating pollutant discharges to navigable waters, attaining water quality standards that provide for the protection of fish, shellfish, and wildlife, and providing federal financial assistance for the construction of publicly owned treatment works (POTW) facilities.

Section 311 of the CWA addresses the control of oil and hazardous substance discharges and provides the authority for promulgation of a regulation to prevent, prepare for, and respond to such discharges. Specifically, section 311(j)(1)(C) mandates regulations establishing procedures, methods, equipment, and other requirements to prevent discharges of oil from vessels and facilities and to contain such discharges.

Through an executive order, the President delegated the authority to regulate non-transportation-related onshore and offshore facilities to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the authority to regulate transportation-related onshore and offshore facilities to the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG), which currently operates under the authority of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Both EPA and the USCG have consistently interpreted and administered section 311 as applicable to spills of non-petroleum-based oils (particularly because of the common physical and chemical properties of animal fats and vegetable oils) and petroleum oils, as well as their common potential for adverse environmental impact when discharged into water.

Oil Pollution Act

- The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 streamlined the EPA’s ability to prepare for and respond to catastrophic oil spills.

In response to a devastating oil discharge into Alaska’s Prince William Sound in 1989 from an ocean vessel, as well as other major oil spills, Congress enacted the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA). OPA streamlined and strengthened the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) ability to prepare for and respond to catastrophic oil discharges.

Specifically, OPA expanded prevention and preparedness activities, improved response capabilities, ensured that shippers and owners or operators of facilities that handle oil pay the costs associated with discharges that do occur, expanded research and development programs, and established an Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund.

OPA section 4202(a)(6) amended Clean Water Act (CWA) section 311(j) to require promulgation of regulations to require owners or operators of certain vessels and facilities to prepare and submit facility response plans (FRPs) for responding to a worst-case discharge of oil and to a substantial threat of such a discharge.

OPA defined oil under section 1001 differently than the CWA section 311(a)(1) definition. Under OPA, “oil” means “oil of any kind or in any form, including petroleum, fuel oil, sludge, oil refuse, and oil mixed with wastes other than dredged spoil, but does not include any substance which is specifically listed or designated as a hazardous substance under subparagraphs (A) through (F) of section 101(14) of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (42 U.S.C. 9601) and which is subject to the provisions of that Act.”

The OPA definition did not amend the original CWA definition of oil and, therefore, was not incorporated into the regulation Part 112, the EPA Oil Pollution Prevention Standard.

OPA section 4113(a) required that the President conduct a study to determine whether liners or other secondary means of containment should be used to prevent leaking or aid in leak detection at onshore facilities used for the bulk storage of oil located near navigable waters. Executive Order 12777 tasked EPA with conducting this study.

The study resulted in EPA’s recommendation to initiate a voluntary program to prevent leaks and spills, rather than a regulatory amendment. The agency clarified that it is not necessary for facility owners and operators to install liners in order to comply with the Oil Pollution Prevention Standard. The agency said: “’Effective containment’ does not mean that liners are required for secondary containment areas. Liners are an option for meeting the secondary containment requirements, but are not required.”

Edible Oil Regulatory Reform Act

- EORRA required the federal government to establish separate classes for edible fats and oils from mammals, fish, and vegetables and led to the EPA declaring that non-petroleum oils pose similar environmental hazards to petroleum-based oils.

In 1995, Congress enacted the Edible Oil Regulatory Reform Act (EORRA). The statute mandates that most federal agencies must differentiate among, and establish separate classes for, various types of oils, specifically, animal fats and oils and greases, fish and marine mammal oils, oils of vegetable origin, and other oils and greases (including petroleum).

In differentiating among these classes of oils, EORRA directed the agencies to consider differences in these oils’ physical, chemical, biological, and other properties, and in their environmental effects.

As a result, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) clarified that animal fats and vegetable oils do not markedly differ from petroleum oils in properties or environmental effects, and the agency published a rulemaking establishing regulatory language to address non-petroleum oils more specifically.

Related regulation 40 CFR 109

- The guidelines in Part 109 establish the minimum criteria for the development of state and local contingency plans for responding to and minimizing damage from oil discharges.

Part 109 is called “Criteria for State, Local and Regional Oil Removal Contingency Plans.” The criteria in this regulation are provided to assist state, local, and regional agencies in the development of oil removal contingency plans for the inland navigable waters of the U.S. and all areas other than the high seas, coastal and contiguous zone waters, coastal and Great Lakes ports and harbors and such other areas as may be agreed upon between the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of Transportation (DOT).

The guidelines in this part establish minimum criteria for the development and implementation of state, local, and regional contingency plans by state and local governments in consultation with private interests to ensure timely, efficient, coordinated, and effective action to minimize damage resulting from oil discharges. Such plans are directed toward the protection of the public health or welfare of the U.S., including, but not limited to, fish, shellfish, wildlife, and public and private property, shorelines, and beaches. The development and implementation of such plans shall be consistent with the National Oil and Hazardous Materials Pollution Contingency Plan (also known as the National Contingency Plan).

State, local, and regional oil removal contingency plans must provide for the coordination of the total response to an oil discharge so that contingency organizations established thereunder can function independently, in conjunction with each other, or in conjunction with the National and Regional Response Teams established by the National Contingency Plan.

Related regulation 40 CFR 110

- Part 110, the so-called “sheen rule,” helps define what is a reportable discharge of oil on waterways and adjoining shorelines.

Part 110 is called “Discharge of Oil” but is also known as the “sheen rule.” These regulations apply to the discharge of oil prohibited by section 311(b)(3) of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA), as amended, 33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq., also known as the Clean Water Act (CWA).

Part 110 defines a discharge of oil into or upon the navigable waters of the U.S. or adjoining shorelines in quantities that may be harmful under the CWA as that which:

- Causes a sheen or discoloration on the surface of the water or adjoining shorelines;

- Causes a sludge or emulsion to be deposited beneath the surface of the water or upon adjoining shorelines; or

- Violates an applicable water quality standard.

A discharge meeting any of the above criteria triggers requirements to report to the National Response Center (NRC). The failure to report such a discharge may result in criminal sanctions under the CWA.

The appearance of a “sheen” on the surface of the water is often used as a simple way to identify harmful discharges of oil that should be reported. However, the presence of either of the other two criteria also indicates a harmful discharge regardless of whether there is a sheen on the water surface.

Related regulation 40 CFR 112

- Part 112 is the primary regulation that the EPA uses to establish requirements for oil-producing facilities to help prevent harmful discharges of oil and to respond quickly and appropriately to protect waterways if spills do happen.

Promulgated on December 11, 1973, Part 112 is called “Oil Pollution Prevention.” The regulation was mandated by the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA) of 1972 (also called the Clean Water Act (CWA)) for the prevention of oil spills into navigable waters and adjoining shorelines of the U.S. Unlike some other federal environmental programs, the CWA does not authorize the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to delegate the Oil Pollution Prevention Program implementation or enforcement to state, local, or tribal representatives. Therefore, it is entirely implemented and enforced by federal EPA.

SPCC rule

Subparts A through C of Part 112 are often referred to as the spill prevention, control, and countermeasure regulations, or simply the “SPCC rule.” Focusing primarily on facility-related oil spill prevention, preparedness, and response, the SPCC rule is designed to protect public health, public welfare, and the environment from potential harmful effects of oil discharges to navigable waters or adjoining shorelines. The rule requires certain facilities (that could reasonably be expected to discharge oil in quantities that may be harmful into navigable waters of the U.S. or adjoining shorelines) to develop and implement SPCC Plans. The written plans ensure that these facilities put in place containment, controls, and countermeasures that will prevent oil discharges. The requirements to develop, implement, and revise the SPCC Plan, as well as train employees to carry it out, allow facility owners and operators to achieve the goal of preventing, preparing for, and responding to oil discharges that threaten navigable waters and adjoining shorelines.

Facility response plans

Part 112 also includes requirements for facility response plans (FRPs) that address oil discharge preparedness requirements for a subset of SPCC-regulated facilities. These requirements define who must prepare and submit an FRP and what must be included in the plan. The regulations, often referred to as the “FRP rule,” are found in Subpart D of Part 112 (and related appendices). The FRP rule applies to a subset of SPCC facilities, which are those that:

- Have 42,000 gallons or more of oil storage capacity and transfer oil over water to or from vessels; or

- The facility has a total oil storage capacity of one million gallons (or more) and one the following is true:

- There is not sufficient secondary containment for each aboveground storage area;

- The facility is located such that a discharge of oil could harm fish, wildlife, and sensitive environments;

- The facility is located such that discharge of oil would shut down a public drinking water intake; or

- The facility has had a reportable oil discharge within the last five years in an amount greater than or equal to 10,000 gallons.

Related regulation 40 CFR 113

- The regulation limits the liability for oil spills that occur at small oil storage facilities (fixed capacity of 1,000 barrels or less).

Part 113 is called “Liability Limits for Small Onshore Storage Facilities.” This regulation establishes size classifications and associated liability limits for small onshore oil storage facilities with a fixed capacity of 1,000 barrels or less. In fact, Part 113 applies to all onshore oil storage facilities with fixed capacity of 1,000 barrels or less.

When a discharge to the waters of the U.S. occurs from such facilities and when removal of said discharge is performed by the U.S. government pursuant to the provisions of subsection 311(c)(1) of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA), as amended, 33 U.S.C. 1151, et seq., the liability of the owner or operator and the facility will be limited to the amounts specified in section 113.4.

Part 113 does not apply to:

- Those facilities whose average daily oil throughout is more than their fixed oil storage capacity, and

- Vehicles and rolling stock.

Related regulation 40 CFR 120

- Part 120 helps to define the scope of “waters of the U.S.”

Part 120 is called “Definition of Waters of the United States.” The Clean Water Act (CWA) generally prohibits the discharge of pollutants (including oil) into ‘‘waters of the U.S.,” also known as WOTUS, without a permit issued by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or a state or Tribe approved by EPA under section 402 of the Act, or, in the case of dredged or fill material, by the Army Corps of Engineers or an approved state or Tribe under section 404 of the Act.

EPA has struggled to nail down the meaning of “waters of the United States,” since a 2001 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and later decisions. Each EPA administration after that date has attempted to set the scope of waters that are subject to the CWA, and each final rule has faced lawsuits.

The definition of WOTUS at Part 120.2 has been revised several times. What’s more, the agency has proposed another iteration on November 20, 2025, which has yet to be finalized. For the current definition, facilities will want to review the latest Part 120.

Related regulation 40 CFR 300

- Part 300, also known as the National Contingency Plan or NCP, provides the federal government’s blueprint for responding to oil spills and other hazardous substance releases that require a national response.

Part 300 is called “National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan.” The plan, more commonly called the National Contingency Plan or NCP, is essentially the federal government's blueprint for responding to both oil spills and hazardous substance releases that require a national response. The NCP provides the framework for our National Response System and the way in which the different levels of responding organizations coordinate their efforts.

The latest NCP, laid out by Part 300, is structured as follows:

- Subpart A — Introduction

- Subpart B — Responsibility and organization for response

- Subpart C — Planning and preparedness

- Subpart D — Operational response phases for oil removal

- Subpart E — Hazardous substance response

- Subpart F — State involvement in hazardous substance response

- Subpart G — Trustees for natural resources

- Subpart H — Participation by other persons

- Subpart I — Administrative record for selection of response action

- Subpart J — Use of dispersants, and other chemical and biological agents

- Subpart K — Federal facilities [reserved]

- Subpart L — National oil and hazardous substances pollution contingency plan; Involuntary acquisition of property by the government

- Appendix A — The hazard ranking system

- Appendix B — National priorities list

- Appendix C — Requirements for product testing protocols and summary test data: Dispersant baffled flask efficacy and toxicity tests; standard acute toxicity test for bioremediation agents, surface washing agents, herding agents, and solidifiers; and bioremediation agent efficacy test

- Appendix D — Appropriate actions and methods of remedying releases

For more information, refer to:

Covered facilities

- Facility owners/operators need to understand when their facilities are required to report (Part 110) and to prevent and respond to (Part 112) an oil spill.

It’s important for a facility owner or operator to know when a facility falls under the oil discharge notification requirements at Part 110 and the oil pollution prevention and response requirements at Part 112. Failure to comply when required may result in criminal sanctions under the Clean Water Act (CWA). On the flip side, there’s no penalty for reporting unnecessarily under Part 110, and complying with the oil pollution prevention and response requirements of Part 112 when not required may add needless burdens to the facility’s operations.

Part 110 applicability determination

- Notification is required whenever a harmful quantity of oil is discharged, and when that oil reaches navigable waters or adjoining shorelines in the U.S.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) strives to limit the damage done by oil spills through regulations at Part 110 requiring the immediate notification of a discharge of a harmful quantity of oil.

Section 311(b)(3) of the Clean Water Act (CWA) stipulates notification is required when two criteria are met:

- A “harmful quantity” of oil is discharged; and

- That oil discharge is into the navigable waters or adjoining shorelines of the U.S.

Pursuant to CWA section 311(b)(3), release notification regulations for discharges of oil were codified in Part 110 on April 2, 1987. Section 110.3 clarifies that a discharge of a harmful quantity of oil is one that:

- Causes a film or sheen upon or discoloration of the surface of the navigable water or adjoining shorelines,

- Causes sludge or emulsion to be deposited beneath the surface of the navigable water or upon the adjoining shorelines, or

- Violates applicable water quality standards.

The appearance of a “sheen” on the surface of the water is often used as a simple way to identify harmful discharges of oil that must be reported. However, the presence of a sludge or emulsion or of another deposit of oil beneath the water surface, or the violation of an applicable water quality standard, also indicates a harmful discharge regardless of whether there is a sheen on the water surface.

Sludge means an aggregate of oil or oil and other matter of any kind in any form other than dredged spoil having a combined specific gravity equivalent to or greater than water. Water quality standards define the goals for a water body by designating its uses, setting criteria to protect those uses, and establishing provisions such as antidegradation policies to protect water bodies from pollutants.

Addition of any chemical or biological agent, or any other substance, to oil to be discharged that would circumvent the provisions of Part 110 is prohibited.

Exemptions

- Exemptions to reporting requirements exist when oil spills to do not reach navigable waters or adjoining shorelines; when oil is released from a properly functioning vessel engine; for certain approved research and demonstration purposes; and a few others.

Several types of oil spills do not need to be reported.

Discharges that did not reach navigable waters or adjoining shorelines

If a discharge has not reached navigable waters or adjoining shorelines, it is not reportable. For example, if a tank leaks a puddle of oil into a building’s basement, this would be considered a discharge of oil, but it is not reportable if the oil did not reach a navigable water or adjoining shoreline. However, groundwater may be a conduit to navigable water or an adjoining shoreline.

Properly functioning vessel engines

Discharges of oil from a properly functioning vessel engine are not deemed to be harmful; therefore, they do not need to be reported under the Discharge of Oil Standard. However, oil accumulated in a vessel's bilge is not exempt.

Research and development releases

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) may permit the discharge of oil on a case-by-case basis in connection with:

- Research,

- Demonstration projects, or

- Studies relating to the prevention, control, or abatement of oil pollution.

However, the Discharge of Oil Standard specifically forbids the use of any chemical or biological agent, or any other substance, to circumvent the standard.

NPDES-permitted releases

Three types of discharges subject to the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) are exempt from oil spill reporting:

- Discharges in compliance with a permit under section 402 of the Clean Water Act (CWA), when the permit contains either an effluent limitation:

- Specifically applicable to oil, or

- Applicable to another parameter that has been designated as an indicator of oil.

- Discharges resulting from circumstances identified and reviewed and made part of the public record with respect to a permit issued or modified under section 402 of the CWA, and subject to a condition in such permit. This exclusion addresses situations where the source, nature, and amount of a potential oil discharge was identified, and a treatment system capable of preventing that discharge was made a permit requirement.

For example, if a discharger has a drainage system that will route spilled oil from a broken hose connection to a holding tank for subsequent treatment and discharge, the treatment system must be sufficient to handle the maximum potential spill from that source. Spills larger than those contemplated in the public record are not exempted. - Continuous or anticipated intermittent discharges from a point source, identified in a permit or permit application under section 402 of the CWA, which are caused by events occurring within the scope of relevant operating or treatment systems. This exclusion applies to chronic or anticipated intermittent discharges originating in the manufacturing or treatment systems of a facility or vessel, including those caused by periodic system failures. Discharges caused by spills or episodic events that release oil to the manufacturing or treatment systems are not exempt from reporting.

Discharges permitted under MARPOL

Certain discharges beyond the territorial seas (defined as extending three miles seaward from the coast) are allowed if they are permitted under international law. The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), as amended, prohibits the discharge of oily mixtures (defined as mixtures with any oil content) from a tanker except when all of the following conditions are met:

- The tanker is proceeding en route,

- The tanker is more than 50 miles from the nearest land,

- The instantaneous rate of discharge does not exceed 60 liters per mile, and

- The total quantity of oil discharged in any ballast voyage does not exceed 1/15,000 of the total cargo carrying capacity.

In addition, MARPOL allows discharges in quantities verified by a monitoring system to be less than or equal to 15 parts per million, regardless of whether the discharge causes a sheen. Therefore, discharges permitted under MARPOL into waters seaward of the territorial sea are exempt from U.S. oil spill notification requirements. Such discharges may include the operational discharge of limited quantities of oil-water mixtures from ships.

Part 112 applicability determination

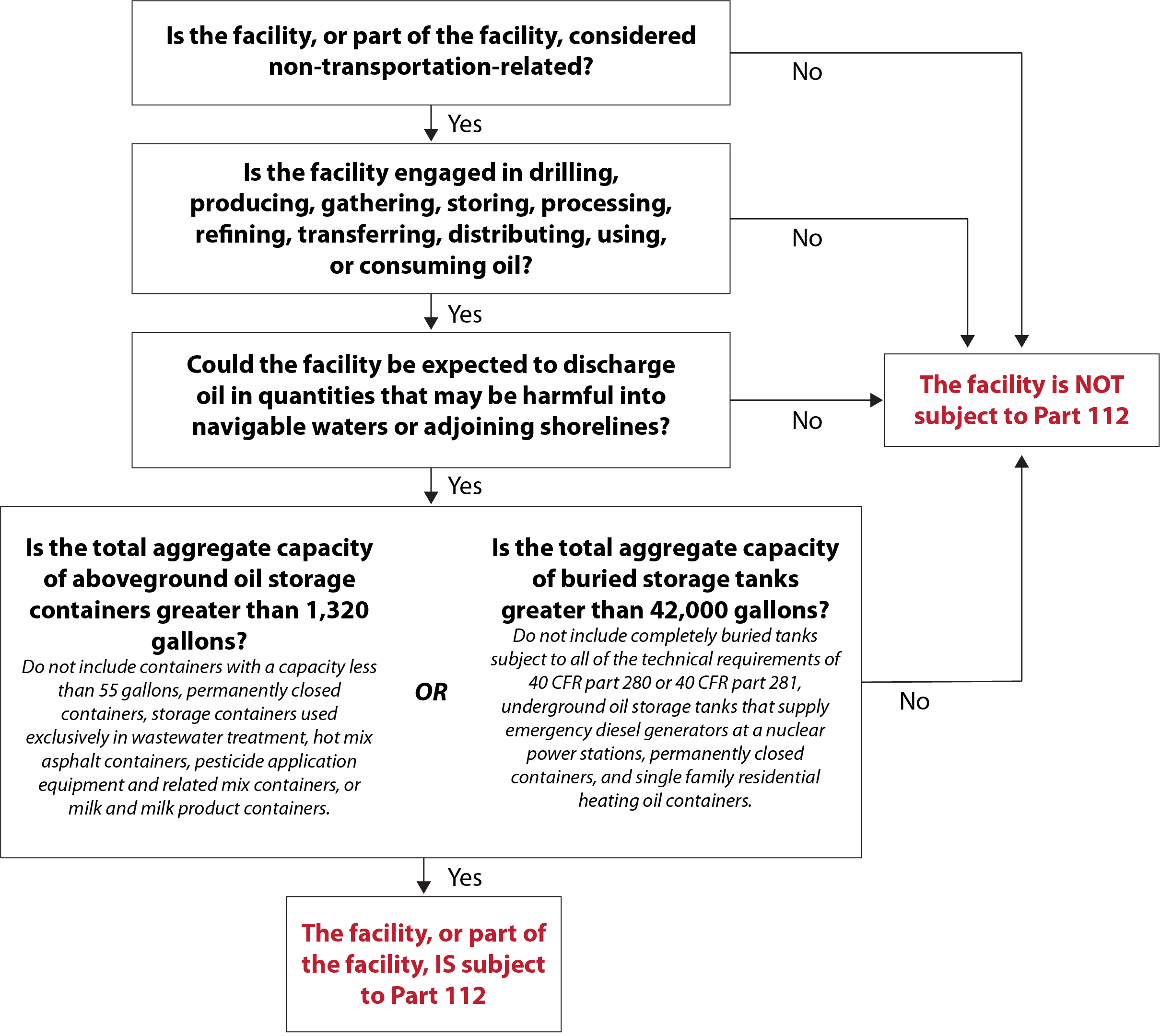

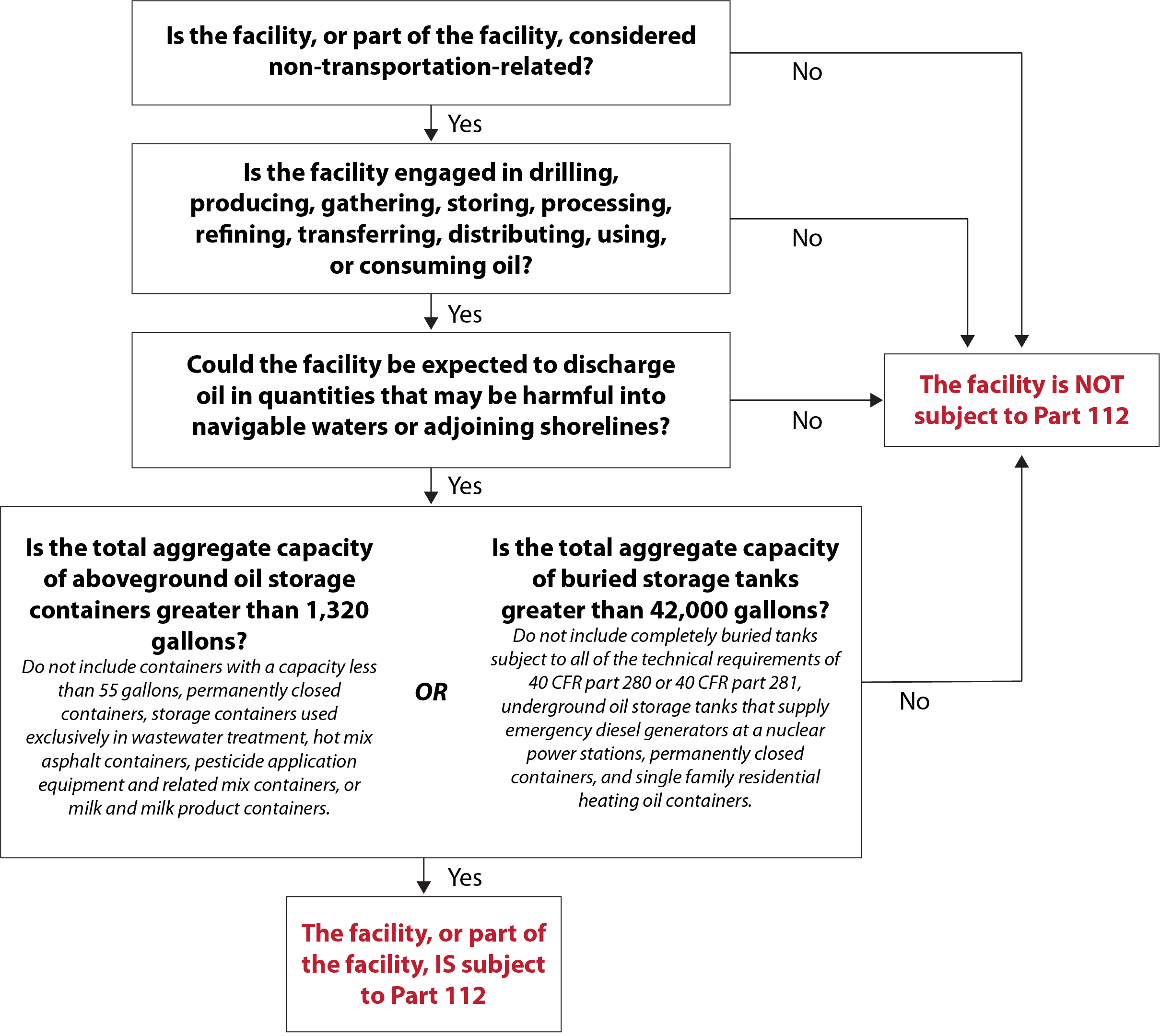

- A facility is covered by the Oil Pollution Prevention Standard (Part 112) if the facility is non-transportation-related; is engaged in certain oil-related activities; could discharge oil in harmful quantities; and has a certain oil storage capacity.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Oil Pollution Prevention Standard strives to limit damage done by oil spills through regulations designed to address a facility's preparedness and its ability to prevent and respond to an oil discharge.

General applicability criteria

The Oil Pollution Prevention Standard at Part 112 applies to facility owners or operators if:

- The facility or part of the facility is considered non-transportation-related; and

- The facility is engaged in drilling, producing, gathering, storing, processing, refining, transferring, distributing, using, or consuming oil or oil products; and

- The facility could reasonably be expected to discharge oil in quantities that may be harmful, and the discharge is to U.S. navigable waters or adjoining shorelines; and

- The facility meets at least one of the following capacity thresholds:

- Aboveground oil storage capacity greater than 1,320 U.S. gallons, or

- Completely buried oil storage capacity greater than 42,000 U.S. gallons.

Below is a flowchart with all four criteria:

Facilities that are owned and operated by federal, state, or local government or tribal entities are equally subject to the regulation as any other facility (although the federal government is not subject to civil penalties).

Activities involving oil

- Some activities that are considered to be oil-related activities include: drilling, producing, gathering, storing, processing, refining, transferring, distributing, or consuming oil or oil products.

Paragraph (b) to Part 112.1 specifies the following oil-related activities are regulated: drilling, producing, gathering, storing, processing, refining, transferring, distributing, using, or consuming oil and oil products. That means these activities are subject to the Oil Pollution Prevention Standard provided the facility meets the other applicability criteria in section 112.1. The table provides examples of these activities.

| Oil-related activity | Examples |

|---|

| Drilling | Drilling a well to extract crude oil or natural gas and associated products (such as wet natural gas) from a subsurface field |

| Producing | Extracting product from a well and separating the crude oil and/or gas from other associated products (e.g., water, sediment) |

| Gathering | Collecting oil from numerous wells, tank batteries, or platforms and transporting it to a main storage facility, processing plant, or shipping point |

| Storing | Storing oil in containers prior to use, while being used, or prior to further distribution in commerce |

| Processing | Treating oil using a series of processes to prepare the oil for commercial use, consumption, further refining, manufacturing, or distribution |

| Refining | - Separating crude oil into different types of hydrocarbons through distillation, cracking, reforming, and other processes

- Separating animal fats and vegetable oils from free fatty acids and other impurities

|

| Transferring | Transferring oil between containers, such as between a railcar or tank truck and a bulk storage container, or between stock tanks and manufacturing equipment |

| Distributing | Selling or marketing oil for further commerce or moving oil using equipment such as highway vehicles, railroad cars, or pipeline systems in the confines of a non-transportation-related facility. Note that businesses commonly referred to as oil distributors and retailers are also “storing” oil, as described in this table |

| Using | Using oil for mechanical or operational purposes in a manner that does not significantly reduce the quantity of oil, such as using oil to lubricate moving parts, provide insulation, or for other purposes in electrical equipment, electrical transformers, and hydraulic equipment |

| Consuming | Consuming oil in a manner that reduces the amount of oil, such as burning as fuel in a generator |

Container types

- Facilities are subject to Part 112 if they have oil in aboveground containers; buried tanks; containers used for seasonal or temporary storage; or tanks that are partially buried or contained in a vault.

Under subparagraphs 112.1(b)(1) through (4), the Oil Pollution Prevention Standard is applicable to eligible facilities that have oil in:

- Aboveground containers;

- Completely buried tanks;

- Containers that are used for standby storage, for seasonal storage, or for temporary storage, or are not otherwise “permanently closed;” and

- “Bunkered tanks” or “partially buried tanks” or containers in a vault.

Containers include not only oil storage tanks, but also mobile or portable containers such as drums and totes, and oil-filled equipment such as electrical equipment (e.g., transformers and circuit breakers), manufacturing flow-through process equipment, and operational equipment.

Storage capacity thresholds

- Part 112 applies to facilities with oil capacity of more than 42,000 gallons stored underground, or more than 1,320 gallons stored aboveground.

Subparagraph 112.1(d)(2) of the Oil Pollution Prevention Standard limits the applicability to facilities with oil capacity above certain threshold amounts. Specifically, Part 112 applies to a facility that has more than 42,000 U.S. gallons of completely buried oil storage capacity or more than 1,320 U.S. gallons of aggregate aboveground oil storage capacity, provided the facility meets the other applicable criteria set forth in 112.1.

Once a facility is subject to the regulation, all aboveground containers and completely buried tanks are subject to the requirements (unless these containers are otherwise exempt from the regulation). For example, a facility could have 10,000 U.S. gallons of aggregate aboveground storage capacity in tanks and oil-filled equipment of 55 U.S. gallons or more, and a completely buried tank of 10,000 U.S. gallons that is not subject to all of the technical requirements of Part 280 or a state program approved under Part 281 (and therefore not exempt). Since the aboveground storage capacity exceeds 1,320 U.S. gallons, all of the tanks and oil-filled equipment, including the buried tank, are subject to the Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) rule.

Subparagraphs 112.1(d)(2)(i) and (ii) clarify which containers are included and excluded when calculating total storage capacity at a facility in determining whether it exceeds the volume limits in the regulation.

Under the Oil Pollution Prevention Standard, if a container has the requisite capacity, it does not matter whether the container is actually filled to that capacity. The storage capacity of a container is defined as the shell capacity of the container.

Facility boundaries

- Part 112 helps to define what constitutes a facility for the purposes of SPCC and FRP requirements. An owner or operator may not characterize a facility for the purpose of avoiding SPCC and FRP requirements.

A facility may or may not be subject to the Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) and Facility Response Plan (FRP) rule requirements depending on how the facility owner or operator aggregates buildings, structures or equipment and associated storage or type of activity. However, once the owner/operator determines the facility boundaries for SPCC applicability, then the same boundaries apply for determining applicability of the FRP rule requirements. An owner or operator may not characterize a facility so as to simply avoid applicability of the rule (for example, defining separate facilities around oil storage containers that are located side-by-side or within close proximity, and are used for the same purpose).

A lease may, at the owner or operator’s discretion, constitute a facility but does not necessarily create a facility. According to the definition of facility, contiguous or noncontiguous buildings, properties, leases, structures, installations, pipes, or pipelines under the ownership or operation of the same person may be considered separate facilities. A facility may also consist of parcels that are smaller or larger than an individual lease.

The following factors to determine the boundaries of a facility are not exclusive and simply serve as examples:

- Ownership, management, and operation of the buildings, structures, equipment, installations, pipes, or pipelines on the site;

- Similarity in functions, operational characteristics, and types of activities occurring at the site;

- Adjacency; or

- Shared drainage pathways (e.g., same receiving water bodies).

Farm-specific applicability

- The WRRDA of 2014 changes the way the SPCC rule is applied to farms.

- New rules, when adopted by the EPA, will likely bring more farms under the SPCC rule.

Under the Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) rule (Part 112 Subparts A to C), a farm is “a facility on a tract of land devoted to the production of crops or raising of animals, including fish, which produced and sold, or normally would have produced and sold, $1,000 or more of agricultural products during a year.”

Section 1049 of the Water Resources Reform and Development Act (WRRDA) of 2014 impacts the SPCC rule for farms. Specifically, the law changes certain applicability provisions of the SPCC rule for farms and modifies the criteria under which a farmer may self-certify an SPCC Plan. Details may be found at the following:

- The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) fact sheet called “Oil Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasures (SPCC Program): Farms and the Water Resources Reform and Development Act (WRRDA),” April 24, 2015.

- EPA’s publication called “Oil Storage on U.S. Farms: Risks and Opportunities for Protecting Surface Waters,” EPA-530-R-15-002, June 30, 2015.

The changes are not yet in the regulations at Part 112. EPA expects to promulgate a rule amending the SPCC requirements associated with the applicability thresholds and other WRRDA amendments. However, please note that EPA has said it intends to lower the greater-than-6,000-gallon threshold to greater than 2,500 gallons. Lowering the threshold will bring more farms under the SPCC rule.

Exemptions

- EPA lists several exemptions from Part 112, most related to facility or equipment location, size, capacity, and more.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) exempts the following from Part 112:

- Any facility, equipment, or operation that is not subject to the jurisdiction of EPA under section 311(j)(1)(C) of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as follows:

- Any onshore or offshore facility, that due to its location, could not reasonably be expected to have a discharge as described in 112.1(b). This determination must be based solely upon consideration of the geographical and location aspects of the facility (such as proximity to navigable waters or adjoining shorelines, land contour, drainage, etc.) and must exclude consideration of man-made features such as dikes, equipment, or other structures, which may serve to restrain, hinder, contain, or otherwise prevent a discharge as described in 112.1(b).

- Any equipment, or operation of a vessel or transportation-related onshore or offshore facility subject to the authority and control of the Department of Transportation (DOT), as defined in the memorandum of understanding found at Appendix A to Part 112.

- Any equipment, or operation of a vessel or onshore or offshore facility which is subject to the authority and control of the DOT or the Department of the Interior, as defined in the memorandum of understanding found at Appendix B to Part 112.

- Any facility where the completely buried oil storage capacity is 42,000 U.S. gallons or less AND the aggregate aboveground oil storage capacity is 1,320 U.S. gallons or less.

- Completely buried oil tanks and associated piping and equipment that are subject to all of the technical requirements under Part 280 or 281.

- Underground oil storage tanks, including below-grade vaulted tanks that supply emergency diesel generators at a nuclear power generation facility licensed by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and subject to any NRC provision regarding design and quality criteria, including, but not limited to, 10 CFR 50.

- Permanently closed oil containers.

- Any container with an oil storage capacity less than 55 U.S. gallons.

- Any facility or part thereof used exclusively for wastewater treatment and not used to satisfy Part 112 (the production, recovery, or recycling of oil is not wastewater treatment for the purposes of this exemption).

- Motive power oil containers (the transfer of fuel or other oil into a motive power container at an otherwise regulated facility is not eligible for this exemption).

- Hot-mix asphalt or any hot-mix asphalt container.

- Containers storing heating oil used solely at a single-family residence.

- Pesticide application equipment or related mix containers (with adjuvant oil).

- Intra-facility oil gathering lines subject to the regulatory requirements of 49 CFR 192 or 195, except that such a line’s location must be identified and marked as ‘‘exempt’’ on the facility diagram as provided in subparagraph 112.7(a)(3), if the facility is otherwise subject to Part 112.

- Any milk and milk product container and associated piping and appurtenance.

- Any offshore oil drilling, production, or workover facility that is subject to the notices and regulations of the Minerals Management Service (MMS), as specified in the Memorandum of Understanding found in Appendix B to Part 112. Note that MMS was replaced in 2011 by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE).

Facilities are not required to include exempt oil containers or oil equipment when calculating the total oil storage capacity of the facility.

Terms related to exemptions under Part 112

- Several exemptions exist for Part 112.

The quickest way for a facility to avoid having to comply with the Part 112 exemptions are discussed here.

Permanently closed

- If they meet the proper definition, permanently closed containers are exempt from Part 112 and no longer count toward a facility’s total oil storage capacity.

Permanently closed containers are exempt from Part 112. Once permanently closed, a container no longer counts toward the total facility storage capacity, nor is it subject to the other requirements under Part 112. Part 112 does not require that permanently closed containers be removed from a facility.

In addition, any container brought on to a facility that has never stored oil is not subject to Part 112, nor is it counted toward the facility capacity until it stores oil. Any other container that at one time stored oil but no longer contains oil or sludge, which is brought onto a facility and meets the definition of permanently closed, is not subject to Part 112 nor is it counted toward the facility capacity until it stores oil.

Permanent closure requirements under Part 112 are separate and distinct from the closure requirements in hazardous waste regulations promulgated under Subtitle C of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), such as Part 264.197 and 265.197.

Is it really permanently closed?

Part 112 does not include a provision to temporarily close containers to account for seasonal use of tanks or variable economic conditions and production rates at oil production facilities. In order for a container to be exempt from Part 112 requirements, the container must meet the following criteria for a permanently closed container:

- All liquid and sludge have been removed from each container and connecting line;

- All connecting lines and piping have been disconnected from the container and blanked off;

- All valves (except ventilation valves) have been closed and locked; and

- Conspicuous signs have been posted on each container stating that it is a permanently closed container and noting the date of closure.

A permanently closed container may remain at the facility. However, a facility owner or operator should review state and local requirements, which may require removal of a container when it is taken out of service. When a container is removed from the facility, the Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) Plan must be amended and the technical amendment must be certified.

In the event that a permanently closed container is brought back into use (e.g., to accommodate variations in production rates), the SPCC Plan will need to be amended to reflect the capacity of the permanently closed container if this capacity was previously excluded from the facility total capacity.

- Underground storage tanks are exempt from Part 112 but are subject to other regulations (such as Parts 280 and 281) that require a facility to prevent, detect, and clean up oil spills from such tanks.

Under subparagraph 112.1(d)(4), the Oil Pollution Prevention Standard exempts completely buried storage tanks, as well as connected underground piping, underground ancillary equipment, and containment systems, when such tanks are subject to all of the technical requirements of Part 280 or a state program approved under Part 281 (also known as the Underground Storage Tank (UST) regulations). Although these tanks are exempt from the requirements of Part 112, they must still be marked on the facility diagram if the facility is otherwise subject to the Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) rule (see subparagraph 112.7(a)(3)).

The regulations at Part 280 and Part 281 comprise the UST Program, which requires owners and operators of new tanks and tanks already in the ground to prevent, detect, and clean up releases. Part 112 only recognizes a subset of tanks covered by the UST Program regulations. Specifically, the UST Program defines a UST as a tank and any underground piping that has at least 10 percent of its combined volume underground. However, under Part 112, only completely buried tanks subject to all of the technical UST program requirements are exempt from Part 112. Any tanks that are not completely buried are considered aboveground storage tanks and subject to Part 112.

The following completely buried tanks are either excluded from the definition of UST or are exempt from the UST regulations at Part 280 (and therefore may be subject to Part 112 if they contain oil):

- Tanks with a capacity of 110 U.S. gallons or less;

- Farm or residential tanks with a capacity of 1,100 U.S. gallons or less used for storing motor fuel for non-commercial purposes;

- Tanks used for storing heating oil for consumptive use on the premises where stored;

- Tanks storing non-petroleum oils, such as animal fat or vegetable oil;

- Tanks on or above the floor of underground areas (e.g., basements or tunnels);

- Septic tanks and systems for collecting stormwater and wastewater; •

- Flow-through process tanks;

- Emergency spill and overfill tanks that are expeditiously emptied after use;

- Surface impoundments, pits, ponds, or lagoons;

- Any UST system holding Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) hazardous waste;

- Any equipment or machinery that contains regulated substances for operational purposes such as hydraulic lift tanks and electrical equipment tanks;

- Liquid trap or associated gathering lines directly related to oil or gas production or gathering operations;

- Pipeline facilities regulated under the Natural Gas Pipeline Safety Act of 1968, the Hazardous Liquid Pipeline Safety Act of 1979, or intrastate pipelines regulated under state laws comparable to the provisions of above laws; and

- Any UST system that contains de minimis concentration of regulated substances.

The following are examples of deferrals from the UST regulations (and therefore may be subject to Part 112):

- Wastewater treatment tank systems;

- Any UST systems containing radioactive materials that are regulated under the Atomic Energy Act of 1954;

- Airport hydrant fuel distribution systems; and

- UST systems with field-constructed tanks.

Note that, at an otherwise Part-112-regulated facility, any transfer to or from completely buried storage tanks is regulated because it is a potential source of discharge of oil into navigable waters or adjoining shorelines. Because a loading/unloading rack, or other transfer area, associated with a UST is not typically part of the UST system, it is not subject to all of the technical requirements of Part 280 or Part 281. Therefore, such a loading/unloading rack is regulated under the Part 112 regulations in the same manner as any other transfer equipment or transfer activity located at an otherwise Part-112-regulated facility.

Additional and/or more stringent requirements may exist in a state-approved program under Part 281, and they may also impact Part 112 applicability. For example, a state may choose to regulate a UST used for storing heating oil for consumptive use on the premises where stored. Thus, under the state program the UST is subject to all the technical requirements of a Part 281 program and therefore exempt from Part 112.

Wastewater treatment facilities

- The wastewater treatment exemption excludes from Part 112 those facilities or parts of facilities that are used exclusively for wastewater treatment.

The wastewater treatment exemption, outlined at Part 112.1(d)(6), excludes from the Part 112 requirements those facilities or parts of facilities that are used exclusively for wastewater treatment, and are not used to meet Part 112 requirements. Do not count the capacity of these exempt containers when calculating facility aggregate capacity.

Many of the wastewater treatment facilities or parts thereof are subject to the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) or state-equivalent permitting requirements that involve operating and maintaining the facility to prevent discharges. The NPDES or state-equivalent process ensures review and approval of the facility’s plans and specifications; operation/maintenance manuals and procedures; and stormwater pollution prevention plans (SWPPPs), which may include best management practice (BMP) plans.

For the purposes of the exemption, the production, recovery, or recycling of oil is not considered wastewater treatment. These activities generally lack NPDES or state-equivalent permits and thus lack the protections that such permits provide. The goal of an oil production, oil recovery, or oil recycling facility is to maximize the production or recovery of oil, while eliminating impurities in the oil, including water, whereas the goal of a wastewater treatment facility is to purify water. Additionally, produced water is not considered wastewater and is therefore not eligible for this exemption. However, produced water containers used exclusively for wastewater treatment at dry gas production facilities are eligible for the wastewater treatment exemption.

The exemption also does not apply to a wastewater treatment facility (or part of that facility) that is used to store oil. In those instances, the oil storage capacity must be counted as part of the total facility storage capacity. For example, if there is a 1,000-gallon storage container that contains oil removed from an exempt oil/water separator and a 500-gallon storage container for an emergency generator, the total aboveground storage capacity for the facility would be 1,500 U.S. gallons, and the facility may potentially be regulated by Part 112.

A wastewater treatment facility (or parts of that facility) used to meet a Part 112 requirement, including an oil/water separator used to meet any spill prevention, control, and countermeasure (SPCC) requirement, is not exempt. Oil/water separators used to meet SPCC requirements include those used to satisfy the secondary containment requirements of subparagraphs 112.7(c), 112.7(h)(1), and/or 112.8(c)(2) or 112.8(c)(11). Although not exempt, oil/water separators used to satisfy secondary containment requirements of Part 112 do not count toward storage capacity.

Motive power

- A motive power container is defined as any onboard bulk storage container used primarily to power the movement of a motor vehicle, or ancillary onboard oil-filled operational equipment.

Motive power container means any onboard bulk storage container used primarily to power the movement of a motor vehicle, or ancillary onboard oil-filled operational equipment (Part 112.2). An onboard bulk storage container which is used to store or transfer oil for further distribution is not a motive power container. The definition of motive power container does not include oil drilling or workover equipment, including rigs.

Motive power containers on vehicles used solely at non-transportation-related facilities fall under the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) jurisdiction but are exempt from Part 112. Section 112.1(d)(2)(ii) excludes the capacity of these containers from facility capacity calculations.

Bulk storage container used for propulsion

Containers on motor vehicles that provide the vehicle with a means of propulsion are considered motive power containers. Examples of motor vehicles which have containers used to individually provide their own means of propulsion from location to location within a facility or between facilities include:

- Aircraft,

- Cherry pickers,

- Self-propelled cranes,

- Self-propelled aviation ground service equipment vehicles,

- Self-propelled heavy vehicles (e.g., used in forestry, agricultural, mining, excavation and construction applications), and

- Locomotives.

Ancillary on-board equipment

Ancillary on-board equipment includes hydraulic and lubrication operational oil-filled containers used for other ancillary functions of a motor vehicle. It also includes motor vehicle bulk storage containers that serve a non-operational purpose in addition to the propulsion of the motor vehicle; for example, a bulk storage container that supplies fuel to an engine that provides the propulsion for that motor vehicle, as well as its auxiliary units and functions (e.g., heaters, air conditioning units, and electrical power generation, etc.).

Exclusions from the motive power container definition

The exemption does not include non-self-propelled stationary or towed equipment, such as towed ground service equipment or any type of oil-powered generator (gensets). The following are examples of equipment that are not motive power containers because they do not include containers used for propulsion: •

- Towed aviation ground service equipment,

- Non-self-propelled construction/cargo cranes,

- Non-self-propelled (forestry, agricultural, mining, excavation or construction) equipment,

- Oil-powered generators,

- Fire pumps, and

- Compressors.

An onboard bulk storage container used to store or transfer oil for further distribution is also not a motive power container. An onboard bulk storage container that supplies oil for the movement of a vehicle or operation of onboard equipment, and at the same time is used for the distribution or storage of this oil is not eligible for the exemption. This situation includes, for example, a mobile refueler that has an onboard bulk storage container used to distribute fuel to other vehicles on a site and which also draws its engine fuel (for propulsion) from that bulk container.

Oil drilling and workover equipment (including rigs) are not eligible for the motive power container exemption because they are specifically excluded from the definition of a motive power container. Although drilling and workover rigs are not exempt, other types of motive power containers located at drilling or workover facilities (e.g., trucks, automobiles, bulldozers, seismic exploration vehicles, or other earth-moving equipment) are exempt.

Oil transfers to motive power containers

Regardless of the exemption for motive power containers, oil transfer activities occurring within a Part-112-regulated facility are regulated. An example of such an activity would be the transfer of oil from an oil storage container via a dispenser to a motive power container. This transfer activity is subject to the general secondary containment requirements of 112.7(c).

Intra-facility gathering lines

- Intra-facility gathering lines may fall under the jurisdiction of the EPA and DOT.

Intra-facility gathering lines (i.e., gathering lines found within the confines of a non-transportation-related facility) may be under the jurisdiction of both the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of Transportation (DOT). However, certain DOT requirements for pipelines are considered to be similar in scope to Part 112 regulations. Therefore, intra-facility gathering lines that are subject to DOT regulatory requirements at Part 192 (Transportation of Natural and Other Gas by Pipeline) or Part 195 (Transportation of Hazardous Liquids by Pipeline) are exempt from Part 112 under 112.1(d)(11).

If intra-facility gathering lines are not subject to DOT regulatory requirements (i.e., gathering lines that by statute are subject to DOT jurisdiction, yet are not subject to the DOT regulations), they remain subject to Part 112. Other equipment and piping at an oil production facility (such as flowlines) remain subject to Part 112 requirements. EPA considers intra-facility gathering lines to be subject to EPA’s jurisdiction if they are located within the boundaries of an otherwise regulated Part-112-covered facility.

The exemption requires owners or operators of a facility to identify and mark as “exempt” the location of exempt piping on the facility diagram. This requirement will assist both facility and EPA personnel in defining the boundaries of EPA and DOT jurisdiction and provide response personnel with information used to identify hazards during a spill response activity. More information about facility diagram requirements is provided at Written plans.

Milk and milk product containers

- Milk and milk product containers are exempt from Part 112. Butter, cheese, and dry milk containers are a few examples.

Milk and milk product containers and associated piping and appurtenances are exempt from the Part 112 under subparagraph 112.1(d)(12) and excluded from facility capacity calculations in subparagraph 112.1(d)(2)(ii). Butter, cheese, and dry milk containers are a few examples of milk product containers subject to the exemption.

All milk and/or milk product transfer and processing activities are included in the scope of this exemption from Part 112. For more information on exempted milk and milk product containers, see the final rule in the Federal Register dated April 18, 2011.

What is oil?

- EPA section 112.2 defines what substances are considered oils, based in part on the description included in the Clean Water Act.

- Any substance which is designated as a hazardous substance under CERCLA is not an oil.

To understand the oil-related regulations and their applicability, facilities must first understand the term “oil.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Part 112.2 defines oil as “oil of any kind or in any form, including, but not limited to: fats, oils, or greases of animal, fish, or marine mammal origin; vegetable oils, including oils from seeds, nuts, fruits, or kernels; and, other oils and greases, including petroleum, fuel oil, sludge, synthetic oils, mineral oils, oil refuse, or oil mixed with wastes other than dredged spoil.”

Part 112 applies to the owners and operators of facilities with the potential to discharge oil in quantities that may be harmful to navigable waters or adjoining shorelines. The Part 112 definition of oil derives from section 311(a)(1) of the Clean Water Act (CWA).

Oil Pollution Act (OPA) section 1001 defined oil separately to exclude any substance which is specifically listed or designated as a hazardous substance under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) and which is subject to provisions of that Act. Although oil is defined separately under OPA, that definition did not amend the original CWA definition of oil in section 311(a)(1) and, therefore, was not incorporated into the definition of oil under section 112.2 that applies to both spill prevention, control, and countermeasure (SPCC) and facility response plan (FRP) regulatory requirements. In response to Edible Oil Regulatory Reform Act (EORRA) of 1995 (33 U.S.C. 2720) requirements, the oil definition under section 112.2 was revised to include the categories of oil in EORRA. Those categories are: (1) petroleum oils, (2) animal fats and vegetable oils; and (3) other non-petroleum oils and greases.

The U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) maintains a separate list of substances it considers oil for its regulatory purposes. The list is available on the USCG website and may be used as a guide when determining if a particular substance is an oil. However, for purposes of EPA’s regulations, the USCG list is not comprehensive and does not include all oils that are subject to Part 112.

Petroleum and non-petroleum oil

- Petroleum oil is petroleum in any form. Non-petroleum oil includes, but is not limited to, fats, oils and greases derived from animal, fish, or vegetable sources.

Petroleum oil means petroleum in any form, including but not limited to crude oil, fuel oil, mineral oil, sludge, oil refuse, and refined products.

Non-petroleum oil means oil of any kind that is not petroleum-based, including but not limited to: fats, oils, and greases of animal, fish, or marine mammal origin; and vegetable oils, including oils from seeds, nuts, fruits, and kernels.

Part 112 applies to both petroleum oils and non-petroleum oils. Petroleum oils include, but are not limited to, crude and refined petroleum products, asphalt, gasoline, fuel oils, mineral oils, naphtha, sludge, oil refuse, and oil mixed with wastes other than dredged spoil. Non-petroleum oils and greases include coal tar, creosote, silicon fluids, pine oil, turpentine, and tall oils.

Subpart B of Part 112 covers both “petroleum oils and non-petroleum oils.” Petroleum oils and non-petroleum oils, including synthetic oils, share common physical properties and produce similar environmental effects. Petroleum and non-petroleum oils can enter all parts of an aquatic system and adjacent shoreline, and similar methods of containment, removal, and cleanup are used to reduce the harm created by spills of both types of oils.

Synthetic oil

- Synthetic oils are created by chemical synthesis rather than by refining petroleum or extracting from animal or plant materials.

Synthetic oils are used in a wide range of applications, including as heat transfer fluids, engine fluids, hydraulic and transmission fluids, metalworking fluids, dielectric fluids, compressor lubricants, and turbine lubricants. Synthetic oils are created by chemical synthesis rather than by refining petroleum crude or extracting oil from plant seeds. Oils that are derived from plant material may be considered animal fats and vegetable oils under Subpart C of Part 112.

Animal fats and vegetable oils (AFVOs)

- Animal fat means a non-petroleum oil, fat, or grease of animal, fish, or marine mammal origin. Vegetable oil means a non-petroleum oil or fat of vegetable origin.

Animal fats and vegetable oils are covered under Part 112.

Animal fat means a non-petroleum oil, fat, or grease of animal, fish, or marine mammal origin. Animal fats include, but are not limited to, fats, oils, and greases of animal origin (for example, lard and tallow), fish (for example, cod liver oil), or marine mammal origin (for example, whale oil).

Vegetable oil means a non-petroleum oil or fat of vegetable origin, including but not limited to oils and fats derived from plant seeds, nuts, fruits, and kernels. Examples of vegetable oils include corn oil, rapeseed oil, coconut oil, palm oil, soybean oil, sunflower seed oil, cottonseed oil, and peanut oil.

Produced water

- Produced water is the oil and water mixture that results from the separation of crude oil or gas from the fluids or gases extracted from the oil/gas reservoir.

- Because it can cause harm if discharged, produced water is regulated as oil under Part 112.

Part 112 applies to produced water from an oil well. Produced water is the oil and water mixture resulting from the separation of crude oil or gas from the fluids or gases extracted from the oil/gas reservoir, prior to disposal, subsequent use (e.g., re-injection or beneficial reuse), or further treatment. Produced water’s chemical and physical characteristics vary considerably depending on the geologic formation, usually being commingled with oil and gas at the wellhead, and changing in composition as the oil or natural gas fraction is separated and sent to market.

Produced water is typically collected in produced water containers at the end of the oil and gas treatment process, and often accumulates emulsified oil not captured in the separation process. Under normal operating conditions, a layer of oil may be present on top of the fluids. The amount of oil by volume observed in produced water storage containers varies, but based on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s assessment, is generally estimated to range from less than one to 10 percent by volume and can be greater. Oil may be present not only in free phase, but also in other forms, such as in a dissolved phase, emulsion or a sludge at the bottom of the produced water container.

Oil discharges to navigable waters or adjoining shorelines from an oil/water mixture in a produced water container may cause harm. Such mixtures in the produced water container are regulated as oil under Part 112. Therefore, the capacity of produced water containers counts toward the facility aggregate oil storage capacity. Produced water containers at oil production, oil recycling, or oil recovery facilities are not eligible for the wastewater treatment exemption in subparagraph 112.1(d)(6).

Other substances

- Certain other substances may be regulated as oil, including but not limited to some forms of asphalt, natural gas condensate, oil and water mixtures, denatured ethanol, and biodiesel fuel.

Other substances may pose a challenge to facilities attempting to determine if they have an oil onsite.

Asphalt

Asphalt is a thermoplastic material, composed of unsaturated aliphatic and aromatic compounds, that softens when heated and hardens upon cooling. Within a certain temperature range, it exhibits viscoelastic properties with viscous flow behavior and elastic deformation. All types of asphalt are petroleum oil products, and its composition depends on the source of the crude oil and the process used to manufacture it.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulation Part 112 applies to asphalt cement (AC), as well as to asphalt derivatives such as cutbacks and emulsions. Because of the operational conditions under which AC, cutbacks and emulsions are used and stored, they do pose a risk of being discharged into navigable waters or adjoining shorelines. Although AC is semi-solid or solid at ambient temperature and pressure, it is generally stored at elevated temperatures. Hot AC is liquid — similar to other semi-solid oils, such as paraffin wax and heavy bunker fuels — and therefore is capable of flowing. Cutbacks and emulsions are liquid at ambient temperature, and, because of their low viscosity, they may flow when discharged onto the ground. All of these oils are regulated under Part 112 to prevent discharges to navigable waters or adjoining shorelines.

However, hot-mix asphalt (HMA) and HMA containers are exempt from Part 112. HMA is a blend of AC and aggregate material, such as stone, ground tires, sand, or gravel, which is formed into final paving products for use on roads and parking lots. HMA is unlikely to flow as a result of the entrained aggregate, such that there would be very few circumstances, if any, in which a discharge of HMA would have the potential to reach navigable waters or adjoining shorelines.

Natural gas and condensate

Part 112 does not apply to natural gas (including liquid natural gas and liquid petroleum gas). EPA does not consider highly volatile liquids that volatilize on contact with air or water, such as liquid natural gas or liquid petroleum gas, to be oil. Furthermore, the agency has stated that hydrocarbons in a gaseous phase under ambient pressure and temperature, such as natural gas, present at Part 112-regulated facilities are exempt.

However, natural gas liquid condensate (often referred to as “natural gasoline” or “drip gas”) is an oil subject to Part 112. Condensate can accumulate in tanks, containers, or other equipment. For the purposes of determining applicability, containers with 55 gallons or more in capacity storing condensate must be included in a natural gas facility’s total oil storage capacity calculation.

Oil and water mixtures

Oil and water mixture containers are subject to Part 112. A mixture of wastewater and oil is “oil” under the statutory and regulatory definition of the term (33 U.S.C. 1321(a)(1) and Part 110.2 and 112.2). A discharge of “wastewater containing oil” to navigable waters or adjoining shorelines in a ‘‘harmful quantity’’ (as defined at Part 110) is prohibited. One example of an oil and water mixture is produced water.

Hazardous substances and hazardous waste