Safety professionals need to keep programs fresh, and safety at the top of employees’ minds. It can be a challenge, though. This section is all about providing fresh ideas to kick-start your safety effort. Some will be smaller activities to raise interest, some will be larger projects to make significant change.

Activities

Following are some activities that can assist you in your safety efforts.

Start a safety bulletin board

Safety bulletin boards can be great ways to showcase your safety efforts and to increase awareness of important safety issues. Here are some ideas for items to feature on a bulletin board:

- Injury rates, days without lost time, etc.

- Workers’ comp statistics

- List of safety committee members

- List of emergency responders

- Emergency information

- Training sign-up sheets

- New Safety Data Sheet updates

- Safety committee meeting minutes

- Cost of safety (Indirect and direct accident costs)

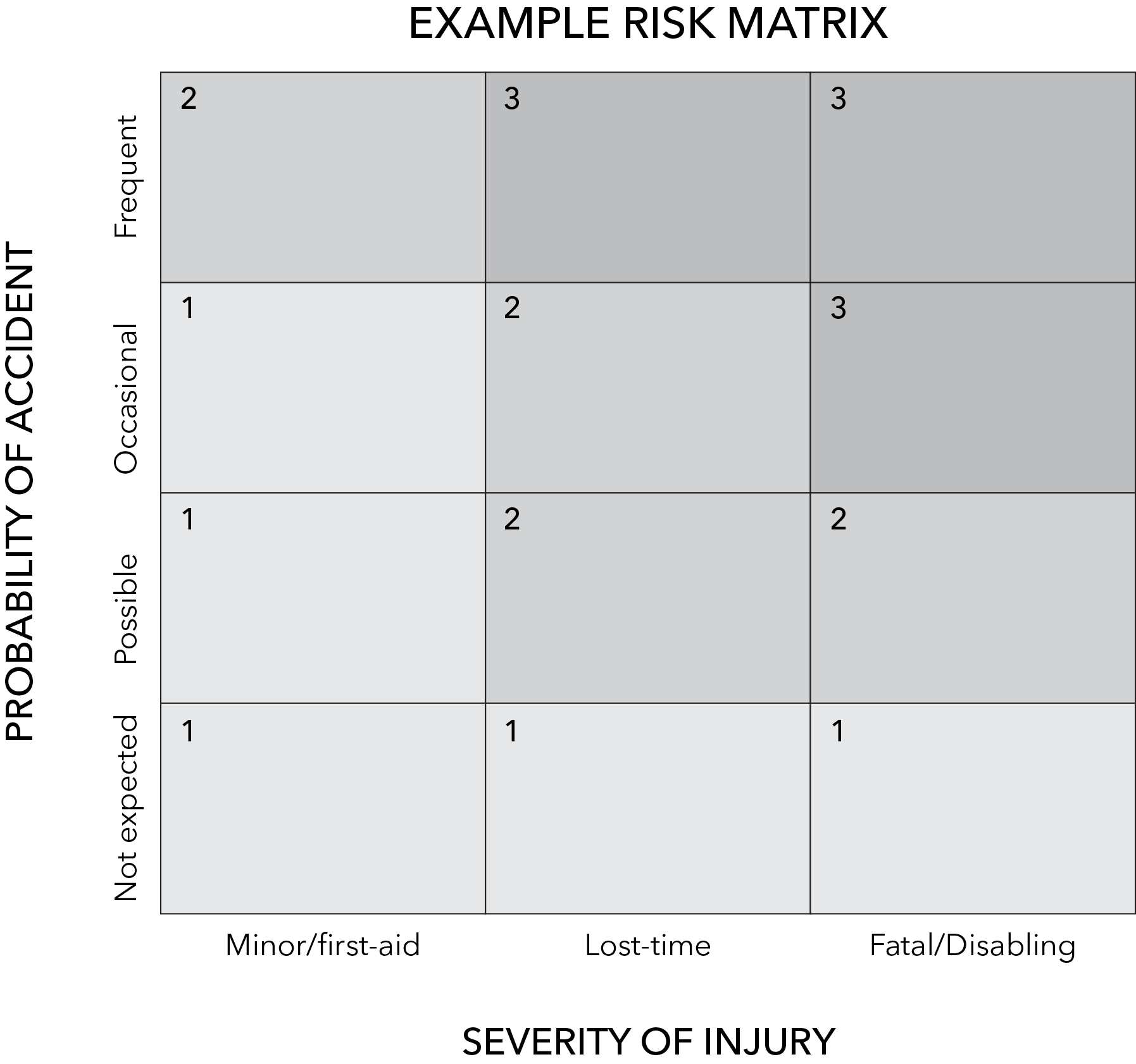

- Risk matrix

- Safety slogans

- Contests/winning entries

- “Caught in the act” (of working safely) (Can also ask employees to bring photos from home of something safety related they did, such as wearing PPE while mowing)

- Pamphlets/handouts (on pertinent safety topics)

- Small mirror with “We are all responsible for safety!” above it

- Cartoons

- Safety suggestion box/forms

- Stretching/exercise illustrations

- Seasonal safety information (e.g., summer = boating safety)

Use your smart phone for safety

With most smart phones these days coming equipped with digital cameras and computing capabilities, it’s a natural fit for safety professionals to utilize the devices on the job. There are countless uses for smart phones when it comes to safety, including:

- Photographing accident scenes;

- Documenting deficiencies during incidents/walkthroughs;

- Calculations/conversions;

- Noise-level measurement;

- Showing safety videos (if your phone has an output feature to a television or projector); and

- Accessing reference materials, to name a few.

Most smart phones will allow you to fairly easily upload your data and pictures to your computer or else access them through the “cloud,” making audit/inspection/investigation reports much easier to manipulate. There are also several apps (applications) pre-made to help you with various safety activities, including:

- NIOSH Ladder Safety app — The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) recently announced the availability of a new Ladder Safety smart phone app. This new app uses visual and audio signals to make it easier for workers using extension ladders to check the angle the ladder is positioned at, as well as access useful tips for using extension ladders safely. The app is available for free download for both iPhone and Android devices. The new smart phone app provides three methods for proper ladder setup:

- Measuring Tool — Actually uses the phone’s positioning capabilities to guide the user through beeps.

- Body Method — Provides instructions based on where the palms/shoulders should be relative to the ladder.

- 4:1 ratio — Provides instructions for using the 4:1 ratio of ladder setup. To learn more and download the Ladder Safety app visit www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/falls/.

- Safe Lifting app from Oregon OSHA — If you’ve ever wondered “how much is too much” for a worker to lift, you’re not alone. Many supervisors and safety professionals have this same question. Given the frequency of lifting in workplace settings, it is surprising to many that OSHA does not set maximum weight limits or provide much guidance on what is a safe lift. To further complicate matters, many of the tools that have been available, such as the NIOSH Lifting Equation, can be complex. There is, however, a new tool developed by Oregon OSHA that allows users to quickly determine how much can be safely lifted. The tool walks users through an illustrated and interactive

3-step process:

- First, users select the beginning position of the lift;

- Next, users pick the lifts per minute and hours of lifting per day; and

- Finally, the results show the lifting weight limit (with an additional limit for more than 45 degrees of twisting during lifting.) To access the tool, visit https://osha.oregon.gov/OSHAPubs/apps/liftcalc/lift-calculator.html

- OSHA Heat Stress app — The app allows workers and supervisors to calculate the heat index for their worksite, and, based on the heat index, displays a risk level to outdoor workers. Then, with a simple “click,” you can get reminders about the protective measures that should be taken at that risk level to protect workers from heat-related illness — reminders about drinking enough fluids, scheduling rest breaks, planning for and knowing what to do in an emergency, adjusting work operations, gradually building up the workload for new workers, training on heat illness signs and symptoms, and monitoring each other for signs and symptoms of heat-related illness. To download the app, visit www.osha.gov/heat/heat_app.html

Uncover your safety culture

As a safety professional, you may have a solid understanding of how your workers feel about the company’s safety program. But, are you certain?

If you really want to find out what people think, meet with workers (usually best if done by department) for a lively discussion on the safety culture. Consider some of these topics:

- Who is responsible for your safety: you, your coworkers, or your employer?

- What has top priority: safety, production, or quality?

- How should hazards be reported and corrected? How should suggestions for safety improvements be handled?

- What is the purpose for accident investigations: to find blame or to prevent recurrence?

- Who should enforce safety rules?

- Is safety training conducted to improve safety or to meet regulatory requirements?

- Should safety performance be included in performance reviews?

- Who should have the final word on safety: management, the safety department, the safety committee, or the employee?

The objectives are to share opinions, establish the current status of the safety program, and identify potential directions for future safety efforts. One goal is to explain why policies are set up the way they are. Policies and procedures are easier to accept when they’re fully understood.

Make it clear that the exercise is just a discussion and that there’s no guarantee that any policies will be changed. But, agree to tell management about any strong concerns that come up. You might get feedback for improving or adding safety programs. Employees may mention training needs, they may give you ideas for how to better recognize safety efforts, or they may identify previously unreported hazards.

Start a program of measuring leading indicators of safety

Measuring safety is always a challenge. Typically, companies look at lagging indicators, such as injury rates. There is a recent push to shift to leading indicators, which refer to ways to measure safety performance prior to or independent of an accident or injury actually occurring; for example, how many safety inspections have been conducted, how many training sessions have been held, or how many employees attended safety meetings. The theory is that if you only look at the incident rate (lagging indicator), you might see that your company has 0 injuries over a given period of time. But, does that mean there were no unsafe behaviors? Does that mean the company was committed to safety? It might. But, it could also just be luck. So, the lagging indicators don’t show you the complete picture.

But, where do you start? Following is a listing of leading indicators that some employers are using:

- Percent of departments conducting self-inspections

- Number of safety committee meetings/percent attendance

- Number of safety presentations

- Supervisor training sessions

- Time from hire to orientation/safety training

- Percent of company goals/objectives that incorporate safety

- Percent of purchasing contracts that include safety stipulations

- Number of behavior-based observations/percent employee participation

- Number of safety suggestions/percent employees

- Number of safety committee projects/successes

- Number of emergency drills/participation

- Audit findings/corrective action time

- Average time to act on safety suggestions

- Percent training on-time

Start a “caught in the act” or “caught working safely” program

When employees work safely, acknowledging it — and/or rewarding it — can reinforce the behavior. Many employers utilize “caught in the act” or “caught working safely” programs where supervisors or safety professionals stop/approach a worker who is exhibiting a safe behavior and issue them a card. The cards can simply be an acknowledgment of the act, or they can be coupons for local restaurants, etc., or worth points that ultimately end up in a raffle, or that can be accumulated and spent (there are several commercial programs of this nature) or turned into vacation time. In addition, some employers have success photographing workers working safely and posting them on a bulletin board, to further drive home the message. A few tips to keep in mind:

- Make the behaviors meaningful, not simply catching someone wearing required PPE. The behaviors should be those things that are above-and-beyond (that show a safety attitude) or that are problem areas that you are targeting (such as safe lifting or team lifting).

- Don’t be stingy with the cards; be on the lookout so all employees have an opportunity to be “caught.”

- It doesn’t have to come from the safety manager. Supervisors can play a great role in handing out the cards.

- Get permission before posting photos on a bulletin board. Some employees may be uncomfortable with the recognition.

Participate in national safety observances

There are many safety observances that can be great opportunities to get your employees involved in safety, as well as helping your company show commitment to safety. These include:

- North American Occupational Safety and Health Week (NAOSH) — Held in May each year; see https://nationaltoday.com/north-american-occupational-safety-and-health-week/.

- Workers’ Memorial Day — April 28 each year. Workers’ Memorial Day is observed every year on April 28. It is a day to honor those workers who have died on the job, to acknowledge the grievous suffering experienced by families and communities, and to recommit ourselves to the fight for safe and healthful workplaces for all workers. It is also the day OSHA was established in 1971.

- Workplace Eye Wellness Month — March each year. For more information, visit www.preventblindness.org.

- Drive Safely to Work Week — In early October each year. For more information, visit www.trafficsafety.org.

Following is a calendar (broken down by quarter) to help you track some of the more popular safety-related observances. Often, the sponsoring organization will provide handouts, posters, presentations, and talking points several weeks in advance; visit their website for additional details. These observances can tie in nicely with safety bulletin board set-up.

Hold a safety fair

Safety fairs can be a great way to get employees across the company involved and excited about safety. Often held in conjunction with wellness fairs, these events give employees a chance to participate both in presenting/exhibiting and also as fair-goers. Here are some tips for hold a fair:

- Start early on with planning. You’ll want to allow at least six months, ideally a year. If possible, start a planning committee made up of department heads to get their buy-in.

- Have a few contests (e.g., slogan, poster) prior to the fair, so you can use the fair to announce/recognize the winners.

- Allow each department/team to come up with their ideas for the fair. Encourage them to make it safety related relative to what their department does.

- Bring in outside help. Medical professionals for blood pressure checks, flu shots, etc. Police for “drunk glasses” and self-defense demonstrations. Fire departments for home safety tips.

- Focus on wellness: blood pressure stations, scales, vision checks, etc., are all fairly easy to set-up.

- Give safety-related prizes for contests/games; for example, flashlights, vehicle emergency kits, fire extinguishers, smoke detectors, premium safety glasses, etc.

Start/revise your incentive programs

If you have been looking to start an incentive program related to safety, or if your current incentive program is heavily tied to the occurrence of injuries/illness, the following are some tips and ideas to consider.

- Focus on proactive measures NOT injury rates. OSHA looks unfavorably on incentive programs that could lead employees to hide injuries in an attempt to retain the incentive. OSHA prefers incentive programs that focus on employee involvement in safety activities, such as participation in a safety committee, attending safety training, or conducting inspections.

- Decide what you want to accomplish. Whether it be general awareness or focus a specific issue, it’s better to have a focus on mind rather than just starting a program just for the sake of starting one.

- Recognize all employees who meet the criteria. Random drawings can lead to bad feelings, particularly if an employee who generally isn’t regarded as caring much about safety wins the drawing. Also, when it comes to supervisor recognition (such as for “on the spot” recognition), make sure all employees who perform safely get recognized.

- Consider individual rewards before group rewards. Individual awards allow employees to control their own destiny so to speak. Group awards often result in either a few employees ruining it for the rest, or a few employees riding the coattails of the other employees and getting the goals.

- Stagger your rewards. It doesn’t have to be all or nothing. If an employee partly completes the objective (e.g., participates in 25 safety observations versus 30), give some reward.

- Remember being safe IS already expected. So, make your rewards focused on those who earn a reward by going above and beyond.

- Beware of the IRS! Incentive programs are likely considered taxable — particularly if you are dealing with monetary rewards, high-value personal property, or awards to a large percentage of employees. Consult with your payroll staff or tax professional. Also, consider reviewing the IRS publications 15-A, 15-B and Publication 525 (www.irs.gov).

What’s the prize?

When it comes to safety incentives, many employers choose to provide prizes. For reasons mentioned above, employers need to be very careful about this, as it can lead to under-reporting of injuries. However, there are many other options available to reward employees:

- Accumulate money and donate to the local fire/emergency responders (or charities).

- Give away safety-related items, such as fire extinguishers, car safety kits, etc.

- Purchase something for the entire department or company (such as new TVs in the break room). These “reminders” will be around much longer than a few dollars for each employee that will be spent quickly.

Get supervisors onboard with safety: Through their Bonuses

There are many reasons line supervisors need to be involved in safety. In many ways they are the ones who can most directly influence an employees’ safe behavior. But, how do you do that? It can be challenging.

One popular approach is to tie safety into supervisors’ bonuses — for example, the year end bonus. Safety should not be the sole criteria for bonuses, but it should be an equal part. (As noted above, anytime safety and incentives and bonuses are tied together it’s a tricky subject. It may be a little more tricky for employees than for supervisors, but still you want to make certain that the bonus/incentive program is actually promoting safety and not hiding injuries.)

One company had success with an approach of utilizing five criteria for forming the supervisors’ year-end bonus. Two of five criteria were safety-related activities (one was the injury rate and the other one was different each year, but was a proactive, forward looking, positive objective that everyone could understand and affect, like “do X number of Job Safety Analyses (JSA) for the year” or do “X number of Safety Notifications.”).

This was very effective at getting supervisor’s attention, as you can find supervisors in any organization that are motivated by money. The company utilized a graded scale — so a target may have been to get 200 JSA’s done for the year, and if the supervisor got 50 done, they would get a percentage of the goal.

The second part of that criteria — the job safety analysis criteria that supervisors were graded on — is key. It’s a positive influence. It is recommended that employers have at least one of these in any sort of bonus program. If an organization only has the injury rate — which really is shaped by negative influence s — it is setting itself up for troubles. For starters, there will be the temptation to hide injuries. But beyond that, with the injury rate, if the employer experiences an injury on January 1 of the year, in some systems the goal is already lost. To have supervisors accept failure early in the year, they can actually become a negative influence on safety. So in addition to not doing anything to promote safety, these types of things can actually negatively affect safety. So employers must be careful and add positive bonus criteria that have an equal weight as criteria such as injury rates.

Departmental “charge-backs”

On the opposite end of the spectrum, some companies utilize negative incentives. For instance, they charge-back costs of accidents to the department. This can be tricky to do — and do fairly — but some companies have figured out ways to do it. Basically, the employers “charge” the department when accidents take place, which in turn directly impacts that department’s budget. The theory is that if you can make any sort of connection between accidents and profits, the department will quickly become more interested in preventing accidents. And, when accidents do happen, they’ll be quick to try to figure out WHY. And, this doesn’t have to be charging them for the actual costs of the accident, but could be some sort of pre-determined charge. Also, by charging the department, you aren’t singling out a supervisor.

Start your library of industry standards

Industry standards, such as ANSI standards, can be invaluable to safety professionals. Unfortunately, most require purchase (though some are relatively inexpensive). However, there are a few — even some very useful ones — that are free to download and/or view online.

NFPA® standards

You may think of NFPA standards as being related to fire safety only. But the fact is, many provide insight into many issues in your workplace, including emergency stops for machinery (NFPA 79), and storage height for empty pallets (NFPA 13). The NFPA makes their standards available to view for free online (no printing/copying/downloading, however). For more information, visit www.nfpa.org.

ITSDF standards

The Industrial Truck Standards Development Foundation (ITSDF) is the secretariat for many industry standards related to powered industrial trucks, such as forklifts. They make many of their standards available for free download. For more information, visit www.itsdf.org.

Local OSHA Area Offices

Your local or regional OSHA office will also likely have copies of many industry standards. They probably will not let you take the materials offsite, but should allow you to view them — you can then determine if the standard would be a benefit to you before purchasing.

Find hidden hazards

Workers may be regularly exposed to, and accept as normal, certain situations as part of doing their routine jobs. No one really recognizes the situations as hazardous because they’ve become so ingrained in the normal procedures that everyone anticipates and puts up with them. For example:

- “When the machine cycles into the pressure release, it gets real loud for a little while;”

- “Sometimes you have to pick defects out of the product — you’ll probably get a few blisters, but you can’t work the tool if you’re wearing gloves;”

- “A lot of dust kicks up when we start filling a new bin;” or

- “The floor gets kind of slippery after the sprayer’s been running awhile.”

An internal safety inspection may acknowledge the situations as normal operating procedures and move on without a second thought. After all, the procedures are likely to be intermittent and of short duration; and “we’ve always done it this way.” It isn’t easy to identify something as hazardous when it’s an obvious part of the daily routine. The inspectors don’t want to be nit-picky, either; they’re out there to find the real problems — the ones that cropped up since the last inspection.

When a normal occurrence is identified as hazardous, it’s easy to think it presents a low risk of serious injury.

However, the hazards may actually present more risk than everyone realizes. Exposures may have cumulative effects.

How do you identify them? A job safety analysis process would help. Other resources could include injury and first aid reports, employee interviews (especially with employees newly assigned to a job), and even worker complaints.

Once identified, the hard work of finding ways to eliminate or control the hazards begins. There isn’t always an obvious quick fix for these problems. Since these hazards likely result from long-established procedures, you’ll have to change attitudes along with equipment, materials, and procedures. Brainstorm with everyone involved to come up with the best solutions. After you get some of the hazards under control, the rest of them should be easier to address; and you’ll find it easier to identify the hazards hiding in the obvious.

Occasionally ask workers about these types of issues and be on the lookout for machines that are constantly being re-started due to jams, etc. Better to intervene now than to risk an actual injury/illness down the road.

Give your supervisors safety tools — without breaking the bank!

It’s no surprise that supervisors play a key role in keeping workplaces safe. They are the ones who know the work best, know the workers best, and are in the best position to ensure employees follow company safety policies and procedures. Naturally, supervisors need safety training — not just on safety-related topics, but also on how to effectively supervise and lead. Holding regular supervisor meetings can be a great way to get them involved. But, you don’t have to stop with just holding the meeting — if you give the supervisors a “take away” tool, it can really reinforce your training and serve as a call to action.

The good thing?

The tools do not have to be expensive to be effective. Consider the following take-away tools for your supervisors.

Inexpensive safety “tools”

- Machine guard opening/distance-to-point-of-operation measuring tool/stick (these are available from many machine safeguarding suppliers/consultants)

- Electrical — GFCI tester, tic tracer

- Inspection checklist packet

- Wallet cards — GHS pictograms, ladder setup, emergency numbers, forklift operator safe behaviors, etc.

- Flashlight, smoke detector for home use

Review your PPE hazard assessment

If your facility has never conducted a baseline hazard assessment on the need for personal protective equipment (PPE) in your workplace, then certainly that should be a priority. But, even if there has been an assessment, if it has been many years since it was done, it may be a good idea to reassess to make sure changes in jobs or processes haven’t created new hazards for which PPE may be needed, OR to see if hazards have been eliminated over the years that would make PPE unnecessary for certain tasks.

How to do a PPE hazard assessment?

A baseline survey is a thorough evaluation of your entire workplace — including work processes, tasks, and equipment — that identifies safety and health hazards. A complete survey will tell you what the hazards are, where they are, and how severe a potential injury could be. Oregon OSHA provides the following suggestions for conducting your PPE hazard assessment:

- Use a safety data sheet (SDS) to identify chemical hazards. An SDS has detailed information about a hazardous chemical’s health effects, its physical and chemical characteristics, and safe handling practices.

- Review equipment owner and operator manuals to determine the manufacturer’s safety warnings and recommended PPE.

- Do a job-hazard analysis. A job-hazard analysis (JHA) is a method of identifying, assessing, and controlling hazards associated with specific jobs. A JHA breaks a job down into tasks. You evaluate each task to determine if there is a safer way to do it. A job-hazard analysis works well for jobs with difficult-to-control hazards and jobs with histories of accidents or near misses. JHAs for complex jobs can take a considerable amount of time and expertise to develop. You may want to have a safety professional help you.

- Have an experienced safety professional survey your workplace with you.

It is also a good idea to involve your employees, particularly for hazards they may be aware of, such as atypical jobs, that you might not catch on a regular walkthrough. In addition, employees can provide great input on how the PPE they are currently using works with the various tasks, as well as comfort. The PPE review should not only focus on whether PPE has been identified for a hazard/task, but also whether the current PPE is the correct PPE for the hazard and the best choice for the job.

PPE policies are often handed down from safety professional to safety professional, with the original baseline having been done decades ago. If that may be the case in your facility, it might be wise to conduct a comprehensive reassessment.

Caution — When hazard assessments are not done

The following provided courtesy of Oregon OSHA:

A worker died from complications resulting from severe burns on his face and hands when he tried to remove the bottom of a 55-gallon drum, which contained traces of motor oil, with a plasma cutter. The drum exploded. He shouldn’t have been using a plasma cutter on an oil drum until it had been cleaned and decommissioned; however, he might have survived with less severe burns if he had been using a face shield and appropriate protective gloves. He was wearing gloves, but they were made with fabric that melted on his hands from the heat of the explosion. His employer had not done a PPE hazard assessment.

In this example, the worker was using a plasma cutter without a face shield and synthetic gloves to cut open a 55-gallon metal drum that had not first been properly cleaned or decommissioned. An effective PPE hazard assessment would produce the following information for the task of using a plasma cutter:

- Task: Using a plasma cutter.

- Hazards: The plasma-cutting arc produces hot metal and sparks, especially during the initial piercing of the metal. It also heats the work piece and the cutting torch. Never cut closed or pressurized containers such as tanks or drums, which could explode. Do not cut containers that may have held combustibles or toxic or reactive materials unless they have been cleaned, tested, and declared safe by a qualified person.

- Likelihood of injury without PPE: High

- Severity of a potential injury: Life-threatening burns

- PPE necessary for the task:

- Body: Dry, clean clothing made from tightly woven material such as leather, wool, or heavy denim

- Eyes and face: Safety glasses with side shield or face shield

- Feet: High-top leather shoes or boots

- Hands: Flame-resistant gloves

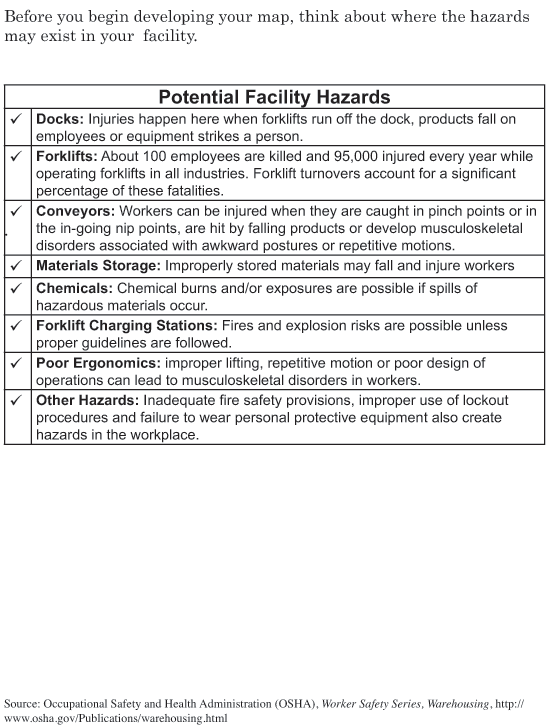

Start a hazard mapping process

Note: The following is adapted, with permission, from: Systems of Safety and Hazard Communication, First Edition – Written and Produced by The Rutgers Occupational Training and Education Consortium (OTEC) and New Labor (For the University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ), School of Public Health, Office of Public Health Practice).

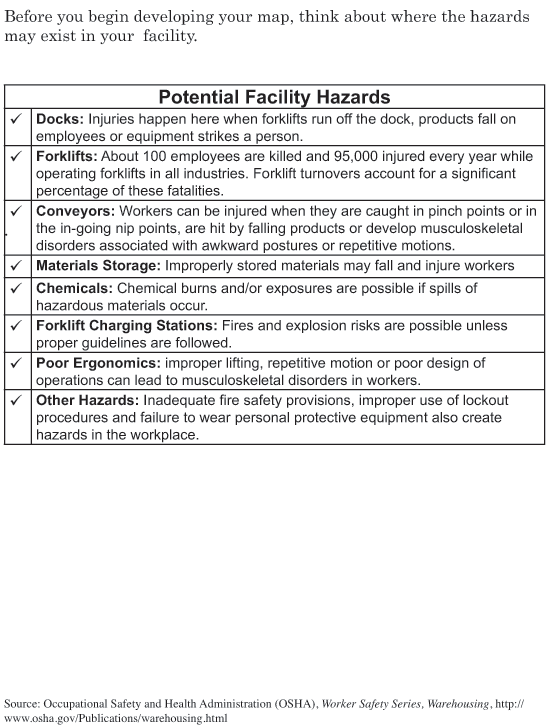

A Hazard Map is a visual representation of the workplace that identifies where there are hazards that could cause injuries. For example, a hazard map might look at the following:

- Physical hazards

- Frequency of exposures

- Levels of exposures

- A specific chemical

- Specific workers or job classifications most likely to be exposed

Hazard maps and worker experiences

Hazard mapping draws on what workers know from on-the-job experience. The hazard mapping approach works best when conducted by a small group of workers from the same department or work area.

Why hazard map?

Hazard mapping can help you identify occupational safety and health hazards. If your workplace has other ways or approaches for identifying hazards, they can be included in your hazard map.

The point of hazard mapping is to gather the knowledge about hazards from co-workers so you can work together to eliminate and/or reduce the risks of accidents and injuries.Hazard mapping respects the vast array of skill, experience and knowledge that workers have about their jobs.

Hazard mapping requires working together to identify, prioritize and solve problems.

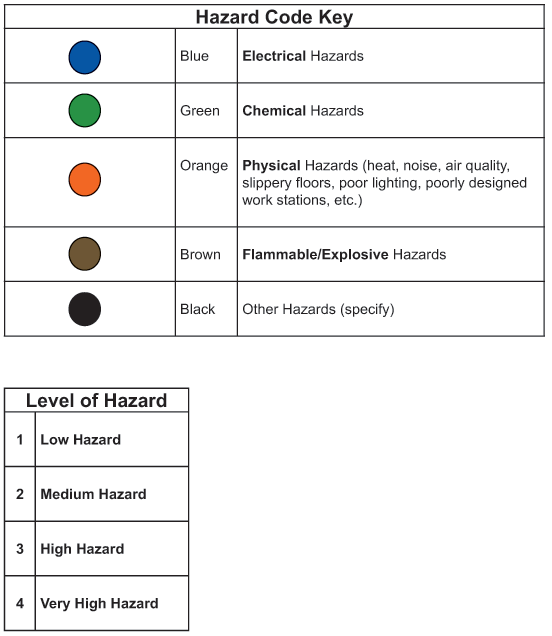

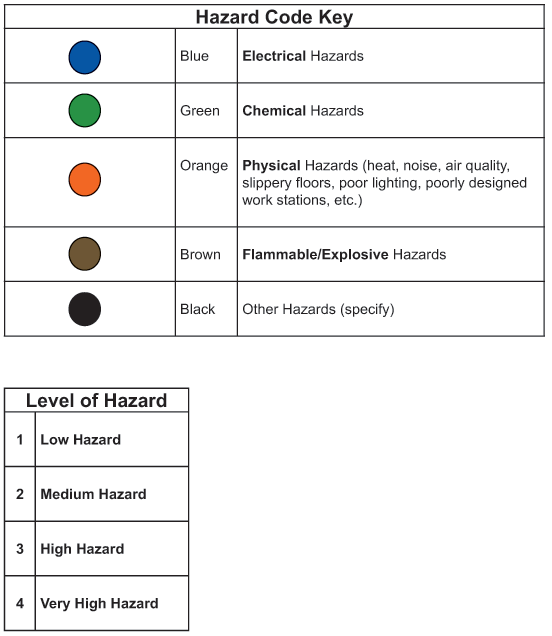

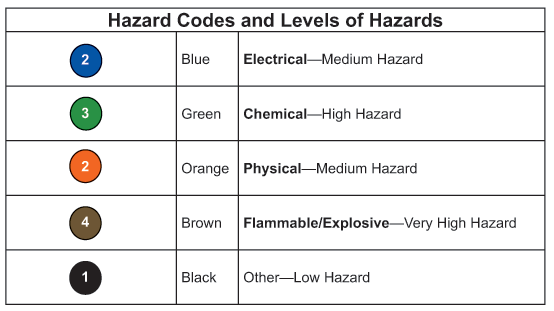

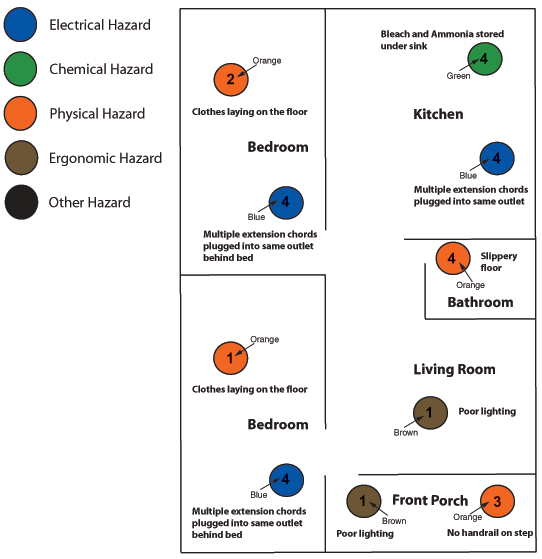

One of the main components of hazard mapping is the system of codes/colors to be used when designating the identified hazards on the illustrated layout/representation of the area or facility. Following is a sample “hazard code key.” Note that the key is typically color-coded. In the print version of this manual, descriptors are shown alongside the circles indicating the color represented.

Hazard mapping labels

Examples of hazard mapping labels

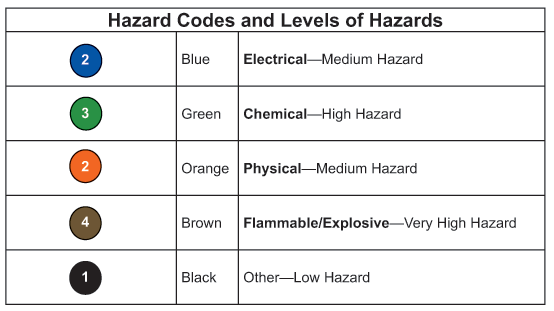

Earlier in this section, a hazard code, as well as a "level of hazard" key was shown. Following is the combination of the two elements, which reveals how the hazard mapping process comes together. The numbers merge with the colored circles to have a specific meaning, e.g. "Electrical — Medium hazard" because of a blue circle (electrical) with a rating of "2" (Medium hazard).

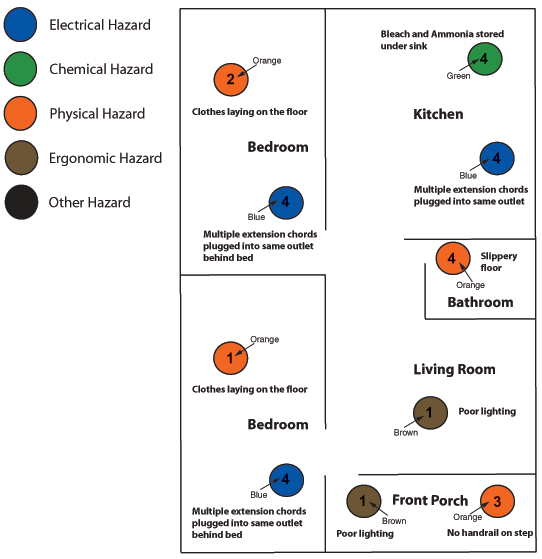

Later in this section a sample layout using the code is applied to a home setting, which most are familiar with — it provides an easy way to illustrate the hazard mapping process.

Identifying areas of concern

Example of home hazard map

Summary

- A Hazard Map is a visual representation of the workplace where there are hazards that could cause injuries.

- Hazard mapping can help you identify occupational safety and health hazards.

- The point of hazard mapping is to gather the knowledge about hazards from your co-workers so you can work together to eliminate and/or reduce the risks of accidents and injuries.

Start a forklift behavioral observation program

Forklifts are prevalent in most operations. And, while OSHA requires a three-year evaluation, and general supervision in between, it can be beneficial to have supervisors conduct more formal frequent checks, and importantly reward operators for exhibiting the desired behaviors. The first step is to develop a list of critical behaviors that you want your operators to perform. Then work with your operators to ensure the behaviors are appropriate, and have them sign off that they will abide by them. Example behaviors include:

- Slows down and sounds horn at intersections,

- Looks in the direction of travel,

- Wears seat-belt (if equipped),

- Keeps hands inside the truck,

- Drives a safe speed,

- Stays in designated aisles,

- Makes smooth and deliberate movements, and

- Other behaviors that are appropriate for your organization (you might consider reviewing injury/incident records for appropriate root causes).

Each quarter have supervisors conduct unannounced observations of operators. When they notice the behaviors, supervisors should give the operator a small reward or recognition. Rewards can be given for individual behaviors, or when the operators has demonstrated all the desired behaviors or a set number.

Ensure temporary worker safety

Temporary staffing agencies and host employers share control over the employee, and are therefore jointly responsible for temp employees’ safety and health. It is essential that both employers comply with all relevant OSHA requirements. Host employers should:

- Work with a reputable staffing agency. Ask to see their safety programs.

- Arrange for a site visit with the temporary agency, so they can learn your operations, hazards, and need for work.

- When feasible, exchange and review injury and illness prevention programs with the staffing agency.

- Define the scope of the work in the contract with the staffing agency.

- Assign responsibility for various aspects of compliance and safety. In some cases, the staffing agency will be in best position to provide the training or compliance, in others, it will be the host employer.

- Make sure your job descriptions and expectations of roles are clearly written out and explained to temp worker candidates.

- Only allow temporary workers to perform work within the scope of the contract.

- Request and review the safety training and any certification records of the temporary workers who will be assigned to the job.

- Keep injury and illness records, if supervising the temporary worker’s work.

- Provide — either separately or jointly with the staffing agency — safety and health orientations for all temporary workers on new projects or newly-placed on existing projects.

- Provide temporary workers with safety training that is identical or equivalent to that provided to the host employers’ own employees performing the same or similar work.

- Train temporary employees on emergency procedures including exit routes.

Use your safety policy as a working part of your program

Most employers have a company safety policy outlining the organization’s philosophy on and commitment to safety. And, most companies inform employees of that policy at the time of hire or when the policy is implemented/changed. Sadly, for most companies, that’s where the policy ends. But, it doesn’t have to — a company safety policy can be a working and active part of your safety program.

For example, some companies have found it beneficial to print the company safety policy on a wall-sized banner that covers a wall in the shop floor. All employees sign the policy banner. Then, when a worker commits a safety violation (i.e., a violation of a well-communicated safety rule, or displays a general disinterest in safety), the company management takes the employee to the wall and points to the signature that the worker understands the policy and will work to uphold it.

The safety policy can also work as a recruitment tool or an aid in contracting — if it is displayed on the company’s external website. Most employers display their policy on the intranet, but not all display it for the larger community to see. With OSHA’s recent push to make negative information available via OSHA.gov, employers can be proactive in putting out positive safety information about their company.

Show upper management commitment to safety

What’s the best way to show upper management commitment to safety? Give them a voice! And, make that voice heard. How do you do that? The following activities, adapted from OSHA’s Safe + Sound initiative, can help:

Send an email blast

A good way to get management involved in safety is to encourage upper management to send an email blast. The email can focus on any number of safety topics, but should include a key message about your company’s commitment to safety and health. Use this email, or a series of emails, to:

- Share why safety is important to management;

- Show how injury and illness prevention is tied to organizational goals and values;

- Provide recognition for positive outcomes from existing safety and health strategies; or

- Highlight upcoming investments in safety and health.

Ideally, the email blast will begin on a Monday. You can also include a different health and safety message each day of the week. For example, one day’s email could feature your upcoming safety activities, another day could highlight safety resources available at your worksite (e.g., trainings, job hazard analysis forms), and the last day could summarize how you will use what you learned during the week to establish or improve your safety and health program.

Create a video

Record an interview with the head of the company talking about why safety is important to them and/or demonstrating how to properly operate equipment, use personal protective equipment, or conduct a task safely in your workplace. You could also invite workers to interview the boss about his or her commitment to safety. Have senior managers host a screening for all workers and show the video during new worker orientation. A simple video shot on any smartphone should suffice.

Write a company newsletter column or article

Start a senior manager column in your company’s newsletter to reiterate your commitment to safety in the workplace. This column could feature organizational goals for safety and health; recognize workers for their safety and health efforts and participation; or report the outcomes of analysis and action taken to address identified concerns or hazards. Ideally, managers will focus on the safety and health best practices they have used first-hand, in the first person. It is also very impactful when management tells a story about how safety (or a lack of good hazard controls) has affected them personally, and why it’s so important to them now.

Find or become a safety mentor

Does an organization you work with have safety efforts or results you would like to emulate? If so, ask the lead safety officer or a peer at that company to serve as your safety mentor. Likewise, if you have a successful safety and health program, consider mentoring a colleague at a supplier, customer, or related organization who is trying to get a fledging program underway. Mentorship is a way to improve your relationships and help strengthen both organizations.

To find mentoring opportunities, try the local chapter of your industry trade association, safety professionals’ organizations, or an OSHA Voluntary Protection Program (VPP) participant near you. Following are some groups that may be helpful:

Jumpstart your safety program in 10 easy steps

If you are not quite ready to implement a complete safety and health program, here are some simple steps you can take to get started. Completing these steps will give you a solid base from which to take on some of the more structured actions you may want to include in your program.

- Always set safety and health as the top priority. Tell your workers that making sure they finish the day and go home safely is the way you do business. Assure them that you will work with them to find and fix any hazards that could injure them or make them sick.

- Lead by example. Practice safe behaviors yourself and make safety part of your daily conversations with workers.

- Implement a reporting system. Develop and communicate a simple procedure for workers to report any injuries, illnesses, incidents (including near misses/close calls), hazards, or safety and health concerns without fear of retaliation. Include an option for reporting hazards or concerns anonymously.

- Provide training. Train workers on how to identify and control hazards in the workplace.

- Conduct inspections. Inspect the workplace with workers and ask them to identify any activity, piece of equipment, or material that concerns them. Use checklists, such as those in the Identify and Control Hazards section of this publication.

- Collect hazard control ideas. Ask workers for ideas on improvements and follow up on their suggestions. Provide them time during work hours, if necessary, to research solutions.

- Implement hazard controls. Assign workers the task of choosing, implementing, and evaluating the solutions they come up with.

- Address emergencies. Identify foreseeable emergency scenarios and develop instructions on what to do in each case. Meet to discuss these procedures and post them in a visible location in the workplace.

- Seek input on workplace changes. Before making significant changes to the workplace, work organization, equipment, or materials, consult with workers to identify potential safety or health issues.

- Make improvements. Set aside a regular time to discuss safety and health issues, with the goal of identifying ways to improve the program.

Use your OSHA 300 log to uncover hazards

Most workplace injuries and illnesses don’t just happen — they are usually predictable and preventable. That’s why OSHA calls them “incidents” instead of “accidents.”

While using a different word might seem like a small thing, it’s part of a huge shift underway. It’s a shift toward prevention — finding and fixing hazards before they lead to injury or illness. It’s like choosing between putting out fires after they damage people and property and making sure fires never start in the first place.

This is where your OSHA 300 log comes in. The log is not just a way to look at your past safety and health record, and it’s not just something for OSHA. It’s a powerful tool to help you identify hazards in your workplace so you can correct them and prevent future injuries and illnesses.

- Think of the 300 log as part of your road map to finding and fixing hazards. For example: “Slip and fall” injuries might tell you that there are housekeeping-related hazards to correct or procedures to adjust.

- A back injury might show you that there is a need for lifting equipment or better training in safe lifting techniques.

- A needlestick injury might indicate that you need to improve your needlestick prevention program and/or implement safer needle devices.

- A fall-related injury might indicate the need for improvements in fall protection or training.

You should examine the log regularly (at least annually), to look for trends. The log should indicate the types of injuries or illnesses that have occurred, their frequency, and the specific processes, activities, tasks, or equipment/material involved.

You can use this information to “find and fix” safety and health problems. [Note: Make sure to review injuries or illnesses among temporary or contractor employees you may have working onsite as well.] Using the 300 log to identify injury and illness trends is a good first step in identifying hazards and demonstrating management commitment to safety and health. Involving workers in reviewing the log and making recommendations for correcting hazards will make this step much more effective.

Start tracking SIFs (Serious Injuries and Fatalities)

Consider the following two scenarios:

- A worker is doing some work on top of a railcar. He slips, but doesn’t fall. He suffers a strained back.

- A worker is walking across the parking lot. He slips, but doesn’t fall. He suffers a strained back.

What we have are two work-related cases, likely to end up on the OSHA logs. Both would go down as back strains. The question is: How related are the two incidents? How related should the interventions be? If you went back through injury records and noticed you had two back strains in the past month, would it concern you that much? Should it?

It’s all about potential

Most would agree that in the situation with the railcar, there is a high probability that a serious injury COULD have occurred, if the worker had actually fallen off the railcar. That’s not to say that a worker couldn’t be seriously injured falling in a parking lot, but the probability is less.

That is the concept behind SIFs: Identifying, intervening, and tracking exposures, either actual or potential, where there is the liklihood of a serious injury or fatality.

Ask many plant managers how the safety program is doing and they’ll say “Good, our injury rates are as low as they’ve been in years.” Then, when a serious injury happens, they’re blindsided. Obviously you don’t want them to be blindsided, so you want to prevent as many serious injuries and fatalities as you can. But, also you want to make sure that management understands the true picture of what’s going on — and that involves more than just the recordable rate. You need to teach them about the SIF rate also.

What the data says

A quick look at the data shows that in 2016 the number of recordable incidents declined to near record-low numbers. However, in the same year, a total of 5,190 fatal work injuries occurred, the highest since 2008.

And, this is a common occurrence in companies who have analyzed their data — that is, the serious injury and fatality rate is not dropping at the same rate as the recordable rate.

So, what gives?

For many years, companies have focused most attention on lagging indicators, such as OSHA’s recordable incident rate, to assess how they are performing year to year.

Further, there is a long-held belief that reducing the number of incidents (recordables) would reduce the number of serious and fatal events (SIFs) (or as some have referred to them, FSI for Fatalities and Serious Injuries). However, data is showing that’s not the case. Focusing on the causes of minor injuries has no major correlation to the future occurrence of a serious or fatal injury.

For example, one company had a 10-year span of declining recordable incident rates, with the highest yearly rate around 6.0. The company is doing something right, right? When that company looked at their fatalities during that same period, they discovered there had been over 60. Most safety professionals would agree that 60 workplace fatalities over a 10-year span is not indicative of a perfectly functioning safety system.

Another issue is the focus on the “safety pyramid,” which has been used for years to correlate near misses and minor injuries to more serious injuries and fatalities, for example for every 1 major injury, there are 29 minor injuries, and 300 near misses. The theory was that focusing on near misses would automatically reduce the number of serious injuries.

Studies are showing that the triangle is not predictive because not all injuries or near misses actually have the potential to cause a SIF. This means that a reduction or intervention at the bottom of the triangle (i.e., near misses) will not necessarily correspond to an equivalent reduction in SIFs. Actually the number is closer to 20 percent.

What you can do

First, you have to target SIFs independently of other injuries and hazards. They are not equal in terms of their causes. Take for example an incident that could result in a minor cut. That may be the worst injury that could happen from the exposure. On the other hand, if you take a burn injury, maybe a slight shift in positioning or pressure could have taken the minor burn to a major one.

To do this, it’s important to create a list of SIF exposures in your work environment. You can start this by reviewing injury and near miss records for the past several years. How many could have been SIFs? What are the common elements of those that met that criteria?

Next, create a list of SIF exposures. These will vary from company to company, but common examples are:

- Fall from greater than 6 feet

- Electrical work

- Confined space

- High-pressure line rupture

- Rigging/lifting-related incident

- Mobile equipment contacting electrical line

- Forklift/pedestrian contact

- Material handling equipment falling from loading dock

- Lockout/tagout or machine guarding failure

- Motor vehicle incident

- Non-routine task

- Combustible dust

You should communicate this list with a campaign to kick off the new SIF focus. You should also target any new SIFs with aggressive hazard controls.

At the same time, you should create an initial SIF rate. This is calculated similarly to your incident rate or DART rate, only you substitute in actual and potential SIF incidents:

(Actual SIF incidents + Potential SIF incidents) * 200,000 / Total Hours Worked = SIF rate

From there, you evaluate every new incident to see if it fits into your new SIF criteria.

Start communicating your SIF rate annually to employees and management, so it is top of mind.

Set effective, SMART leading indicators

Good leading indicators are based on SMART principles, meaning they are Specific, Measurable, Accountable, Reasonable, and Timely:

- Specific: Does your leading indicator provide specifics for the action that you will take to minimize risk from a hazard or improve a program area?

- Measurable: Is your leading indicator presented as a number, rate, or percentage that allows you to track and evaluate clear trends over time?

- Accountable: Does your leading indicator track an item that is relevant to your goal?

- Reasonable: Can you reasonably achieve the goal that you set for your leading indicator?

- Timely: Are you tracking your leading indicator regularly enough to spot meaningful trends from your data within your desired timeframe?

The chart below, adapted from OSHA’s Using Leading Indicators to Improve Safety Outcomes, demonstrates how to create a SMART leading indicator to address the issue that workers have not been attending monthly safety meetings. It walks through a good and bad example for meeting each SMART criterion using the leading indicator “Number of workers who attend a monthly safety meeting.”

Example Leading indicator: Number of workers who attend a monthly safety meeting

Goal: 97% worker attendance rate at monthly safety meetings |

|---|

| SPECIFIC | Does your leading indicator provide specifics for the action that you will take to minimize risk from a hazard or improve a program area? |

GOOD EXAMPLE

Workers will attend a safety meeting every month.

This is specific because it clearly identifies what the activity is and who needs to attend. | BAD EXAMPLE

Safety meetings will be held monthly.

This is not specific because it does not describe who needs to attend. |

| MEASURABLE | Is your leading indicator presented as a number, rate, or percentage

that allows you to track and evaluate clear trends over time? |

GOOD EXAMPLE

Workers will attend a safety meeting every month.

This is measurable because you can track the number of workers that attend every month. | BAD EXAMPLE

Workers will attend safety meetings.

This is not measurable because it does not track a number, rate, or percentage with respect to your goal. |

| ACCOUNTABLE | Does your leading indicator track an item that is relevant to your goal? |

GOOD EXAMPLE

Workers will attend a safety meeting every month.

This indicator is relevant to your goal because it asks workers to

attend the meeting. | BAD EXAMPLE

Safety meetings for workers will be held monthly.

This indicator is not relevant to your goal because it does not

specify that your workers would be asked to attend. |

| REASONABLE | Can you reasonably achieve the goal that you set for your leading indicator? |

GOOD EXAMPLE

Workers will attend a safety meeting every month. Your goal is

a 97% attendance rate.

Your 97% goal is achievable because it takes into account that you will not have a make-up meeting and workers missing work will not be able to attend on the day the meeting is scheduled. | BAD EXAMPLE

Workers will attend a safety meeting every month. Your goal is

a 100% attendance rate.

Your 100% goal is not achievable because you know that some

workers will occasionally miss work on the day the meeting is

scheduled. |

| TIMELY | Are you tracking your leading indicator regularly enough to spot meaningful trends from your data within your desired timeframe? |

GOOD EXAMPLE

You decide to track meeting attendance monthly.

This is timely; because you track your meetings monthly, you can identify meaningful trends before the end of the year, which is when you wanted to analyze your data. | BAD EXAMPLE

You decide to track meeting attendance twice a year.

Because you only tracked two meetings, you cannot see any

meaningful trends until at least the following year. |

Designate safety advocates

Getting employees to support safety, or even just follow your written procedures, can be a challenge. Supervisor support and reinforcement is critical because they’re the day-to-day contact for employees. As a safety professional, you can’t reinforce safety with every employee every day.

One option could increase compliance while also help to alleviate the burden on supervisors. It involves identifying at least one employee in each team or department to serve as a safety advocate.Even supervisors who fully support safety need to create time for including that obligation among their other duties.

As a result, safety may not be something they devote time to every day.

Creating a program that identifies individual employees to serve as safety advocates, who promote compliance among their peers, could provide much-needed assistance and backup for a busy supervisor. In addition, other workers in the department may be more willing to listen to feedback from a coworker, since the reinforcement won’t seem like an authoritarian demand from management.

Identifying candidates

You’ll need volunteers for a safety advocate program, since the participants should willingly support all safety efforts.

However, supervisors should help identify likely individuals, based on performance and particularly seeking individuals who have the respect of their coworkers. Potential candidates might include individuals who:

- Know someone (friend, family member, coworker) who was injured at work and would like to help others avoid that fate; or

- Have a personal story regarding safety, whether they were injured or experienced a frightening near-miss incident.

Workers may have other relevant backgrounds, for example, military or EMT experience. The goal is finding individuals whose experience helps them understand that “safety is serious.” If you can identify a few individuals and present the safety advocate role as a development opportunity, you may be able to develop safety “deputies” and gain eyes, ears, and peer support for your programs.

Your company may want to provide incentives for participating, but someone who volunteers for a reward is not necessarily the best candidate. The ideal advocate is someone who participates out of a desire to help others.

Running the program

Once a few potential advocates are identified, they’ll need training on their expected roles. You can start small, since even one person from three or four different departments could have a substantial impact in their areas.

When developing training, don’t expect them to learn everything at once. Identify a few key issues that have been challenging in their work areas, and focus only on those areas to start.You can always add additional items in the future.

Training might cover a review of key safety issues, along with guidance on how to gently remind coworkers to follow the rules. For instance, ask them to share the experience that caused them to volunteer or to offer phrases to use such as, “Steve, I’m worried you’ll get hurt reaching past the guard. I have a friend who lost two fingers doing that.” If the potential advocates don’t have their own stories to share, give them examples from your own company’s experience or (if your safety record is strong) from other employers.

Although they’ll be telling friends and peers to “follow the rules” in a practical sense, their purpose is to deliver reminders and encouragement, not to threaten discipline or to report violations. Essentially, these advocates are leading from the middle by inspiring others through their actions, along with giving encouragement.

Keep your drivers safe

Texting while driving dramatically increases the risk of a motor vehicle injury or fatality. Employers need to make it clear to all workers that their company doesn’t require or condone texting while driving. It’s literally a matter of life and death.

Strong policies

- Have a strong policy that prohibits the use of portable electronic devices while driving.

- Establish work procedures and rules that do not make it necessary to text while driving.

- Make safe driving an integral part of your business culture.

Vehicle and driver safety

- Review and consider the safety features of all vehicles used, including late model vehicle safety systems (e.g., collision warning, driving control assistance).

- Check the driving records of all employees who drive for work purposes.

- Ensure vehicles are safe and properly maintained.

- Encourage workers to focus on the road, avoid electronic distractions, slow down in work zones and not drive if fatigued.

Training

- Provide continuous driver safety training and communication.

- Train workers on driving distractions and to not solely rely on navigation and other advanced technology systems.

- Instruct drivers to take extra precautions during inclement weather.

- Ensure drivers know procedures, times and places for drivers to use phones and other technologies for communicating with managers, customers and others.

Training

Incorporate a forklift obstacle course for your training

Forklift training is required to have a hands-on aspect. Nothing is more hands-on (and fun) than a forklift obstacle course. If you don’t currently utilize a course, they can be relatively easy and inexpensive to set up. The following are some tips on creating an obstacle course where trainees work on picking up a load, carrying a load, turning, backing, and stopping at intersections.

Caution: Exercises should be conducted under the supervision of a qualified forklift operator trainer.

What you will need:

- 40 x 60 foot clear area

- Traffic cones or empty pallets

- Box on pallet

- Tape

Steps:

- Place traffic cones to form course. See illustration on following page. (Pallets or a combination of pallets/cones can also be used.)

- Place load as shown in illustration. (Can be on the floor or in a rack.)

- Designate load drop point as shown in illustration. (Can be on the floor or in a rack.)

- Tape floor to show intersections.

Exercises:

- Have trainee pick up the pallet and navigate through the course.

- Have trainee place the load in the designated load drop point.

- Have trainee back down the aisle and then proceed back to start point.

When done, discuss the following:

- Lifting the load. Look at the approach, fork position, smoothness of lift and tilt.

- Traveling with a load. Look at speed and height of forks.

- Placing the load. It should be placed squarely and securely.

- Reading the workspace layout/design. Were there sudden stops or jerking motions or other difficulties with maneuvering?

- Challenges with backing. Did trainee face the direction of travel?

- Sounding the horn at intersections. Also, did trainee slow down?

- Specific challenges or questions raised by the trainee’s performance.

Course enhancements:

Depending on your available space, you can use the same general design but enhance it with additional stops, aisles, or turns. For example, place traffic cones in the middle of the aisle and require the trainee to slalom through.

In addition, you can challenge trainees by using different loads, or an uneven load that the operator should stabilize or secure before picking, or depending on attachments, a drum or roll.

Combustible dust training

Use the CSB’s safety videos

If your facility has the potential for combustible dust or chemical hazards, the Chemical Safety Board’s video series can be extremely useful for training. The videos contain stellar graphics and present real-life case studies. To access the videos, visit http://www.csb.gov/videos/.

Safe behavior training

It doesn’t always come to mind when we think of workplace safety, but our own behaviors play a key role in keeping us free of injury.

Think about it. When you drove to work this morning, you probably took the time to put on your seat-belt … a safe behavior. Why did you do that?

Chances are, either you did it because it has become second-nature.

Or you did it because you didn’t want to receive a traffic ticket for not wearing it.

Or you did it because you know it’s the safe thing to do and see the value in it.

Or you did it because you wanted to set a good example for your children who you were dropping off at school.

But, what about that time a few weeks ago when you were just moving the car to the street, so your spouse could back out of the driveway. Did you buckle up then? Or what about the time when you were a passenger in your coworker’s backseat and didn’t see the seat-belt attachment … did you buckle up then? Did you ask or tell your friend to stop the car?

The point here is that behavior is a very complex issue. It involves a series of attitudes, beliefs, experiences, consequences, environmental factors, and other issues.

It is important to highlight these behavioral issues to workers and explain how they relate to safety at work.

Unfortunately, we often let factors — whether outside or internal — influence our behavior in a negative way. Where safety is concerned, this can be fatal.

Take for example the case of John, a maintenance worker at a manufacturing facility. John hadn’t got much sleep the night before because he was up late with his sick child. It was nearing 3:30 in the afternoon, and John really wanted to go home. He just had one quick job to finish up. It was an easy one — one he’d done many times before. So, he decided to save some time and skip the company’s procedure to lock out the energy source on machinery before working on it. Unfortunately, the machine cycled, and John lost his left arm.

Regardless of the outside or internal influences, workers must follow proper safety procedures and policies.

But, it’s a complex issue, because there are many reasons a worker might choose an unsafe behavior. For example, it may help do something quicker or easier and often workers are not injured as a result of the unsafe behavior. The following exercises can help you teach your employees about the impact behaviors have on safety.

Exercise: All about activators

Objectives: Use this exercise to give trainees an opportunity to identify activators and their impact on behaviors.

Ask the trainees to provide examples of activators (for example, a speed limit sign, an icy patch on the road, a no smoking sign, a gas gauge, a ringing telephone). Display responses so the group can view them.

When you have a sufficient number of responses, then ask the group to describe what behavior might be triggered by the activator (for example, place foot on the brake, remove foot from accelerator, put out cigarette, pull car over and pump gas, answer telephone).

After you have a sufficient list of activators and behaviors, discuss the relationship between the two, and point out how multiple activators (for example, a speed limit sign + a police car, or ice on the road + a car on the side of road in a ditch) might cause a stronger response than a single activator; how people respond differently to the same activators (for example, a person who got a speeding ticket last week may respond differently to a speed limit sign than someone who has not), etc.

Works well with: Small groups.

Materials required: A means to display group responses (Flip-chart, whiteboard, overhead, etc.)

Preparation time: 15-20 minutes to think of activators and behaviors.

Exercise: Negative versus positive consequences

Objectives: Use this exercise to give trainees an opportunity to think about negative and positive consequences.

Give trainees a few scenarios (can use clip art or photos, or a simple description) of various behaviors (for example, someone lifting a new television, someone putting on safety glasses, someone driving in wintry conditions). Ask them to list positive and negative consequences for each behavior (for example, get to watch the game on a new television versus a back injury from improper lifting). Display responses so the group can see them.

Works well with: Small groups.

Materials required: A means to display group responses (Flip-chart, whiteboard, overhead, etc.)

Preparation time: 15-20 minutes to think of behaviors to be used and examples of consequences.

Reach ALL your workers with training

All workers learn at different paces and in different ways. Language and literacy levels play a key role in learning outcomes.The following suggestions, excerpted from an OSHA publication on training methods, are designed to help trainers adapt training techniques to reach participants at all skill/literacy levels.

These techniques will also be helpful in teaching participants for whom English is a second language (sometimes referred to as English Language Learners (ELL)).

- Do not assume that all participants are equally skilled or confident in speaking, reading, writing, and math.

- Plan for plenty of small group activities where participants get to work together on shared tasks — reading, discussing, integrating new information, relating to life experience, recording ideas on flip charts, and reporting back to the whole group. In small groups, participants can contribute to the tasks according to their different backgrounds and abilities.

- Try to use as many teaching techniques as possible that require little or no reading.

- At the beginning of a class mention that you are aware that people in the group may have different levels of reading and writing skills.

- Establish a positive learning situation where lack of knowledge is acceptable and where questions are expected and valued. Participants need to be able to indicate when they do not understand and to feel comfortable asking for explanations of unfamiliar terms or concepts.

- Make it clear that you will not put people on the spot. Let them know that you are available during breaks to talk about any concerns.

- Let the group know that they will not necessarily be expected to read material by themselves during the training.

- Let people know that you will not be requiring them to read aloud. Ask for volunteers when reading aloud is part of an activity. Never call on someone who does not volunteer.

- Do not rely on printed material alone. When information is important, make sure plenty of time for discussion is built into the class so participants have the opportunity to really understand.

- Read all instructions aloud. Do not rely on written instructions or checklists as the only way of explaining an activity or concept.

- If other materials must be read aloud, read them yourself or ask for a volunteer.

- Make sure your handouts are easy to read and visually appealing.

- Give out only the most important written material. Make any other materials available as an option.

- If possible, provide audio recordings of key readings so that participants have the option to listen and read along.

- Explain any special terms, jargon, or abbreviations that come up during the training. Write them on a flip chart.

- If participants have to write, post a list of key words. This can serve as a resource for people with writing or spelling difficulties.

Make your training slides more readable

While slides are an important part of most training presentations, if they are not designed properly, they can actually hinder the training. Here are a few tips to make your training slides more user friendly:

- One concept per slide.

- Use a simple design.

- Make sure you really understand how to create and design slides. It takes some knowledge and skill to develop a presentation. For instance, getting the animation correct can be tricky.

- Do not make the mistake of designing the slide with too many graphics and animation (a common error among instructors). This can result in a design that is too complicated and difficult to read. Go easy on the graphics. Simple graphics that are easily understood are best. Do not use graphics just to make a slide look good; only use them if they have some content value. Keep animation to a minimum.

- Use lots of white space.

- Use contrast: dark on light, or light on dark. In choosing colors, make sure that the text is easy to see.

- Design from top left to bottom right.

- Use large font sizes (26 point minimum). No more than two fonts on a page.

- Limit use of bolding, italics, and underlining.

Demonstrate ergonomic principles in a practical way

For most safety professionals and trainers, ergonomic principles can be difficult to grasp, as they often involve an understanding of the way our musculoskeletal system works, along with principles of physics. This means they are also difficult to teach, which is vital if workers are to utilize proper techniques to eliminate injury.

Several years ago, NIOSH produced a publication that contains practical guidance on explaining ergonomic principles. This document was developed for individuals who provide training on ergonomic principles that focus on MSD risk-factor exposures. It was designed for trainers of all experience levels including the beginning trainer.

The demonstrations are designed to be performed by both the trainer and the worker. Each demonstration reinforces specific ergonomic principles and teaches the worker how and why to avoid MSD risk factors.

Additionally, individuals involved in the purchase and selection of new and/or replacement tools may benefit from many of the demonstrations because they highlight the importance of considering ergonomic principles before purchasing tools.

Now, NIOSH has placed a video supplement to the publication online for free access.

The video demonstration highlights worker participation and uses relatively inexpensive materials. The demonstrations are organized by type of ergonomic principle. Five general topics are addressed:

- Neutral compared with nonneutral postures;

- Grip types;

- Hand-tool selection and use;

- Fatigue failure and back pain; and

- Moment arms and lifting.

To access the video, visit http://bit.ly/2li1WmU.

To access the guidance publication, visit http://bit.ly/2kUwWgU.

Format of the guide

Each section of this document begins with a discussion of an ergonomic principle and its role in avoiding MSD risk factors, followed by a series of demonstrations that may be used to show how the principle can be incorporated into the work environment.

Each demonstration starts with clear objective statements and concludes with take-home messages that participants should incorporate into their everyday thinking.

These demonstrations encourage audience participation because discussing how the principle plays a role in a worker’s specific workplace is important for promoting understanding.

Each demonstration includes the following information:

- Objectives of the demonstration,

- List of suggested supplies needed to conduct the demonstration,

- Step-by-step demonstration methodology,

- Take-home messages that should be emphasized during the demonstration.

Sample demonstration - The pen and paperclip exercise

Repeated lifting, even at sub-maximal levels, may eventually lead to damage of the spine (fatigue failure). Substantially reducing loads placed on the spine can greatly minimize the risk of fatigue failure.

But, how do you teach this concept to workers? The NIOSH Guide uses an exercise called the “pen and paperclip exercise.”

Supplies

One plastic pen cap (the type with a stem/tail)

One paper clip for each audience member

Step-by-step demonstration method:

- Take intact pen cap and bend the “tail” once.

- Show audience members that there is a discoloration at the spot where the bending occurred, which is a visual example of sub-failures occurring.

- Continue to bend the pen cap about five times, and then show the audience that the discoloration has expanded.

- Explain to the audience that, if you continue to bend the pen cap, it would eventually fail.

- Explain to the audience that, for some materials (e.g. paper clip, vertebrae), fatigue failure is not visible.

- Distribute one paper clip to each audience member.

- Ask the audience to bend the paper clip back and forth, and count the number of cycles it can withstand before breaking.

- Ask various audience members how many cycles it took before the paper clip failed; emphasize that the number of cycles varies for the paper clips as no one paper clip is exactly the same as another. This is also true for people and their vertebrae. Just like with the paper clips, some workers will experience fractures in their vertebrae very quickly as others require many cycles despite undergoing the same loading conditions.

- Show the graph in Figure 24 to the audience. Editor’s note: In the NIOSH publication, “Figure 24” contains photos of a pen cap that is bent multiple times, visibly showing fatigue; a photo of a paper clip shows the result of failure (no fatigue).

- Explain that every type of material has an ultimate load (i.e., the load at which it fails when that load is applied only once). The graph in Figure 24 of the NIOSH publication illustrates the amount of loads the spine can handle without breaking. Because every spine is unique, the ultimate load varies somewhat for each spine. Thus, the y-axis of this graph represents the percentage of ultimate load. The x-axis represents the number of cycles a load was applied. For example, if you applied a load to a spine that was 80% of its ultimate load, you would be able to apply that load 100 times before the spine would fail. Likewise, if you applied a load that was only 50% of its ultimate load, you could apply that load 1,000 times before failure. If you applied a load that was only 30% of its ultimate load, you could complete an infinite number of loading cycles without the spine ever failing.

- Explain to the audience that this means they are not doomed to having a back injury. Rather, if the load applied to the spine is decreased substantially, they could perform their job an infinite number of times and never injure their spine. You may also increase your core strength to better handle loads — a balanced body in terms of abdominal and back strength makes a more stable core when trained together.

- Discuss ways to reduce the load applied to the spine, such as decreasing the weight of the object, reducing the moment arm (which is demonstrated in the NIOSH publication), removing barriers, and eliminating twisting and back flexion.

Take home messages

Often, the vertebrae of the back can have multiple sub-failures that are not visible but can result in complete failure over time.

The number of cycles that lead to failure of the vertebrae varies across the population.

Efforts should be made to substantially decrease loading of the spine.