...

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs

41 CFR Part 60-20

RIN 1250-AA05

Discrimination on the Basis of Sex

AGENCY: Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, Labor.

ACTION: Final rule.

SUMMARY: The U.S. Department of Labor's Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs publishes this final rule to detail obligations that covered Federal Government contractors and subcontractors and federally assisted construction contractors and subcontractors must meet under Executive Order 11246, as amended, to ensure nondiscrimination in employment on the basis of sex and to take affirmative action to ensure that applicants and employees are treated without regard to their sex. This rule substantially revises the existing Sex Discrimination Guidelines, which have not been substantively updated since 1970, to align them with current law and legal principles and address their application to contemporary workplace practices and issues. The provisions in this final rule articulate well-established case law and/or applicable requirements from other Federal agencies and therefore the requirements for affected entities are largely unchanged by this rule.

DATES: Effective Date: These regulations are effective August 15, 2016.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Debra A. Carr, Director, Division of Policy and Program Development, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, 200 Constitution Avenue NW., Room C-3325, Washington, DC 20210. Telephone: (202) 693-0104 (voice) or (202) 693-1337 (TTY). Copies of this rule in alternative formats may be obtained by calling (202) 693-0104 (voice) or (202) 693-1337 (TTY). The rule also is available on the Regulations.gov Web site at http://www.regulations.gov and on the OFCCP Web site at http://www.dol.gov/ofccp.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Executive Summary

Purpose of the Regulatory Action

The U.S. Department of Labor's (DOL) Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) is promulgating regulations that set forth the obligations that covered 1 Federal Government contractors and subcontractors and federally assisted construction contractors and subcontractors (contractors) must meet under Executive Order 11246, as amended 2 (the Executive Order or E.O. 11246). These regulations detail the obligation of contractors to ensure nondiscrimination in employment on the basis of sex and to take affirmative action to ensure that they treat applicants and employees without regard to their sex.

1 Employers with Federal contracts or subcontracts totaling $10,000 or more over a 12-month period, unless otherwise exempt, are covered by the Executive Order. See 41 CFR 60-1.5(a)(1). Exemptions to this general coverage are detailed at 41 CFR 60-1.5.

2 E.O. 11246, September 24, 1965, 30 FR 12319, 12935, 3 CFR, 1964-1965, as amended.

OFCCP is charged with enforcing E.O. 11246, which prohibits employment discrimination by contractors on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity,3 or national origin, and requires them to take affirmative action to ensure that applicants and employees are treated without regard to these protected bases. E.O. 11246 also prohibits contractors from discharging or otherwise discriminating against employees or applicants because they inquire about, discuss, or disclose their compensation or the compensation of other applicants or employees.4 OFCCP interprets the nondiscrimination provisions of the Executive Order consistent with the principles of title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (title VII),5 which is enforced, in large part, by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the agency responsible for coordinating the Federal Government's enforcement of all Federal statutes, executive orders, regulations, and policies requiring equal employment opportunity.6

3 Executive Order 13672, issued on July 21, 2014, added sexual orientation and gender identity to E.O. 11246 as prohibited bases of discrimination. It applies to covered contracts entered into or modified on or after April 8, 2015, the effective date of the implementing regulations promulgated thereunder.

4 Executive Order 13665, issued on April 8, 2014, added this prohibition to E.O. 11246. It applies to covered contracts entered into or modified on or after January 11, 2016, the effective date of the implementing regulations promulgated thereunder.

5 Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2000e-17; U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, Federal Contract Compliance Manual, ch. 2, §2H01, available at http://www.dol.gov/ofccp/regs/compliance/fccm/FCCM_FINAL_508c.pdf (last accessed March 25, 2016) (FCCM); see also OFCCP v. Greenwood Mills, Inc., No. 00-044, 2002 WL 31932547, at *4 (Admin. Rev. Bd. December 20, 2002).

6 Executive Order 12067, 43 FR 28967, 3 CFR 206 (1978 Comp.). The U.S. Department of Justice also enforces portions of title VII, as do state Fair Employment Practice Agencies (FEPAs).

OFCCP's Sex Discrimination Guidelines at 41 CFR part 60-20 (Guidelines) have not been substantively updated since they were first promulgated in 1970.7 The Guidelines failed to conform to or reflect current title VII jurisprudence or to address the needs and realities of the modern workplace. Since 1970, there have been historic changes to sex discrimination law, in both Federal statutes and case law, and to contractor policies and practices as a result of the nature and extent of women's participation in the labor force. Issuing these new regulations should resolve ambiguities, thus reducing or eliminating any costs that such contractors previously may have incurred to reconcile conflicting obligations.

7 35 FR 8888, June 9, 1970. The Guidelines were reissued in 1978. 43 FR 49258, October 20, 1978. The 1978 version substituted or added references to E.O. 11246 for references to E.O. 11375 in paragraphs 60-20.1 and 60-20.5(c), but otherwise did not change the 1970 version.

It is long overdue for part 60-20 to be updated. Consequently, OFCCP issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) on January 30, 2015 (80 FR 5246), to revise this part to align the sex discrimination standards under E.O. 11246 with developments and interpretations of existing title VII principles and to clarify OFCCP's corresponding interpretation of the Executive Order. This final rule adopts many of those proposed changes, with modifications, and adds some new provisions in response to issues implicated in, and comments received on, the NPRM.

Statement of Legal Authority

Issued in 1965, and amended several times during the intervening years—including once in 1967, to add sex as a prohibited basis of discrimination, and most recently in 2014, to add sexual orientation and gender identity to the list of protected bases—E.O. 11246 has two purposes. First, it prohibits covered contractors from discriminating against employees and applicants because of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, or national origin; it also prohibits discrimination against employees or applicants because they inquire about, discuss, or disclose their compensation or the compensation of other employees or applicants. Second, it requires covered contractors to take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are considered, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, or national origin. The nondiscrimination and affirmative action obligations of contractors cover a broad range of employment actions.

The Executive Order generally applies to any business or organization that (1) holds a single Federal contract, subcontract, or federally assisted construction contract in excess of $10,000; (2) has Federal contracts or subcontracts that, combined, total in excess of $10,000 in any 12-month period; or (3) holds Government bills of lading, serves as a depository of Federal funds, or is an issuing and paying agency for U.S. savings bonds and notes in any amount.

The requirements of the Executive Order promote the goals of economy and efficiency in Government contracting, and the link between them is well established. See, e.g., E.O. 10925, 26 FR 1977 (March 8, 1961) (nondiscrimination and affirmative employment programs ensure “the most efficient and effective utilization of all available manpower”). The sex discrimination regulations adopted herein outline the sex-based discriminatory practices that contractors must identify and eliminate, and they clarify how contractors must choose applicants for employment, and treat them while employed, without regard to sex. See, e.g., §60-20.2 (clarifying that sex discrimination includes discrimination on the bases of pregnancy, childbirth, related medical conditions, gender identity, transgender status,8 and sex stereotyping, and that disparate treatment and disparate impact analyses apply to sex discrimination); §60-20.3 (clarifying application of the bona fide occupational qualification (BFOQ) defense to the rule against sex discrimination); §60-20.4, §60-20.5, §60-20.6, and §60-20.8 (clarifying that discrimination in compensation; discrimination based on pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions; discrimination in other fringe benefits; and sexual harassment, respectively, can be unlawful sex-discriminatory practices); and §60-20.7 (clarifying that contractors must not make employment decisions based on sex stereotypes).

8 A transgender individual is an individual whose gender identity is different from the sex assigned to that person at birth. Throughout this final rule, the term “transgender status” does not exclude gender identity, and the term “gender identity” does not exclude transgender status.

Each of these requirements ultimately reduces the Government's costs and increases the efficiency of its operations by ensuring that all employees and applicants, including women, are fairly considered and that, in its procurement, the Government has access to, and ultimately benefits from, the best qualified and most efficient employees. Cf. Contractors Ass'n of E. Pa. v. Sec'y of Labor, 442 F.2d 159, 170 (3d Cir. 1971) (“[I]t is in the interest of the United States in all procurement to see that its suppliers are not over the long run increasing its costs and delaying its programs by excluding from the labor pool available minority [workers].”). Also increasing efficiency by creating a uniform Federal approach to sex discrimination law, the regulations' requirements to eliminate discrimination and to choose applicants without regard to sex are consistent with the purpose of title VII to eliminate discrimination in employment.

Pursuant to E.O. 11246, the award of a Federal contract comes with a number of responsibilities. Section 202 of this Executive Order requires every covered contractor to comply with all provisions of the Executive Order and the rules, regulations, and relevant orders of the Secretary of Labor. A contractor in violation of E.O. 11246 may be liable for make-whole and injunctive relief and subject to suspension, cancellation, termination, and debarment of its contract(s) after the opportunity for a hearing.9

9 E.O. 11246, sec. 209(5); 41 CFR 60-1.27.

Major Revisions

OFCCP replaces in significant part the Guidelines at part 60-20 with new sex discrimination regulations that set forth Federal contractors' obligations under E.O. 11246, in accordance with existing law and policy. The final rule clarifies OFCCP's interpretation of the Executive Order as it relates to sex discrimination, consistent with title VII case law and interpretations of title VII by the EEOC. It is intended to state clearly contractor obligations to ensure equal employment opportunity on the basis of sex.

The final rule removes outdated provisions in the current Guidelines. It also adds, restates, reorganizes, and clarifies other provisions to incorporate legal developments that have arisen since 1970 and to address contemporary problems with implementation.

The final rule does not in any way alter a contractor's obligations under any other OFCCP regulations. In particular, a contractor's obligations to ensure equal employment opportunity and to take affirmative action, as set forth in parts 60-1, 60-2, 60-3, and 60-4 of this title, remain in effect. Similarly, inclusion of a provision in part 60-20 does not in any way alter a contractor's obligations to ensure nondiscrimination on the bases of race, color, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, and national origin under the Executive Order; on the basis of disability under Section 503 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 503); 10 or on the basis of protected veteran status under 38 U.S.C. 4212 of the Vietnam Era Veterans' Readjustment Assistance Act.11 Finally, it does not affect a contractor's duty to comply with the prohibition of discrimination because an employee or applicant inquires about, discusses, or discloses his or her compensation or the compensation of other applicants or employees under part 60-1.

10 29 U.S.C. 793.

11 38 U.S.C. 4212.

The final rule is organized into eight sections and an Appendix.

The first section (§60-20.1) covers the rule's purpose.

The second section (§60-20.2) sets forth the general prohibition of sex discrimination, including discrimination on the bases of pregnancy, childbirth, related medical conditions, gender identity, transgender status, and sex stereotypes. It also describes employment practices that may unlawfully treat men and women disparately. Finally, the second section describes employment practices that are unlawful if they have a disparate impact on the basis of sex and are not job-related and consistent with business necessity.

The third section (§60-20.3) covers circumstances in which disparate treatment on the basis of sex may be lawful—i.e., those rare instances when being a particular sex is a bona fide occupational qualification reasonably necessary to the normal operation of the contractor's particular business or enterprise.

The fourth section (§60-20.4) covers sex-based discrimination in compensation and provides illustrative examples of unlawful conduct. As provided in paragraph 60-20.4(e) of the final rule, compensation discrimination violates E.O. 11246 and this regulation “any time [contractors] pay[ ] wages, benefits, or other compensation that is the result in whole or in part of the application of any discriminatory compensation decision or other practice.”

The fifth section (§60-20.5), discrimination on the basis of pregnancy, childbirth, and related medical conditions, recites the provisions of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 (PDA); 12 lists examples of “related medical conditions;” and provides four examples of discriminatory practices. This section also discusses application of these principles to the provision of workplace accommodations and leave.

12 Amendment to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to Prohibit Sex Discrimination on the Basis of Pregnancy, Public Law 95-555, 995, 92 Stat. 2076 (1978), codified at 42 U.S.C. 2000e(k).

The sixth section (§60-20.6) sets out the general principle that sex discrimination in the provision of fringe benefits is unlawful, with pertinent examples, and clarifies that the increased cost of providing a fringe benefit to members of one sex is not a defense to a contractor's failure to provide benefits equally to members of both sexes.

The seventh section (§60-20.7) covers employment decisions on the basis of sex stereotypes and discusses four types of gender norms that may form the basis of a sex discrimination claim under the Executive Order: Dress, appearance, and/or behavior; gender identity; jobs, sectors, or industries within which it is considered appropriate for women or men to work; and caregiving roles.

The eighth section (§60-20.8), concerning sexual harassment, including hostile work environments based on sex, articulates the legal standard for sexual harassment based on the EEOC's guidelines and relevant case law and explains that sexual harassment includes harassment based on gender identity; harassment based on pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions; and harassment that is not sexual in nature but that is because of sex or sex-based stereotypes.

Finally, the final rule contains an Appendix that sets forth, for contractors' consideration, a number of practices that contribute to the establishment and maintenance of workplaces that are free of unlawful sex discrimination. These practices are not required.

Benefits of the Final Rule

The final rule will benefit both contractors and their employees in several ways. First, by updating, consolidating, and clearly and accurately stating the existing principles of applicable law, including developing case law and interpretations of existing law by the EEOC and OFCCP's corresponding interpretation of the Executive Order, the final rule will facilitate contractor understanding and compliance and potentially reduce contractor costs. The existing Guidelines are extremely outdated and fail to provide accurate or sufficient guidance to contractors regarding their nondiscrimination obligations. For this reason, OFCCP no longer enforces part 60-20 to the extent that it departs from existing law. Thus, the final rule should resolve ambiguities, reducing or eliminating costs that some contractors may previously have incurred when attempting to comply with part 60-20.

The final rule will also benefit employees of and job applicants to contractors. This final rule will increase and enhance the promise of equal employment opportunity envisioned under E.O. 11246 for the millions of women and men who work for contractor establishments. Sixty-five million employees work for the contractors and other recipients of Federal monies that are included in the U.S. General Service Administration's (GSA) System for Award Management (SAM) database.13

13 U.S. General Services Administration, System for Award Management, data released in monthly files, available at https://www.sam.gov/portal/SAM/#1.

More specifically, the final rule will advance the employment status of the more than 30 million female employees of contractors in several ways.14 For example, it addresses both quid pro quo and hostile work environment sexual harassment. It clarifies that adverse treatment of an employee resulting from gender-stereotypical assumptions about family caretaking responsibilities is discrimination. It also confirms the requirement that contractors provide equal retirement benefits to male and female employees, even if the contractor incurs greater expense by doing so.

14 Bureau of Labor Statistics data establishes that 47 percent of the workforce is female. Women in the Labor Force: A Databook 2, BLS Reports, available at http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-databook-2012.pdf (last accessed March 27, 2016) (Women in the Labor Force). Based on these data, OFCCP estimates that 30.6 million of the employees who work for contractors and other recipients of Federal monies in the SAM database are women.

In addition, by establishing when workers affected by pregnancy, childbirth, and related medical conditions are entitled to workplace accommodations, the final rule will protect such employees from losing their jobs, wages, and health-care coverage. OFCCP estimates that 2,046,850 women in the contractor workforce are likely to become pregnant each year.15

15 OFCCP's methodology for arriving at this estimate was described in the preamble to the NPRM. 80 FR at 5262.

The final rule will benefit male employees of contractors as well. Male employees, too, experience sex discrimination such as sexual harassment, occupational segregation, and adverse treatment resulting from gender-stereotypical assumptions such as notions about family caregiving responsibilities. The final rule includes several examples of such gender-stereotypical assumptions as they affect men. For example, final rule paragraph 60-20.5(d)(2)(ii) clarifies that family leave must be available to fathers on the same terms as it is available to mothers, and final rule paragraph 60-20.7(d)(4) includes adverse treatment of a male employee who is not available to work overtime or on weekends because he cares for his elderly father as an example of potentially unlawful sex-based stereotyping.

Moreover, by clarifying that discrimination against an individual because of her or his gender identity is unlawful sex discrimination, the final rule ensures that contractors are aware of their nondiscrimination obligations with respect to transgender employees and provide equality of opportunity for transgender employees, the vast majority of whom report that they have experienced discrimination in the workplace.16

16 Jaime M. Grant, Lisa M. Mottet, & Justin Tanis, National Center for Transgender Equality & National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey 3 (2011), available at http://www.transequality.org/issues/resources/national-transgender-discrimination-survey-executive-summary (last accessed March 25, 2016) (Injustice at Every Turn).

Finally, replacing the Sex Discrimination Guidelines with the final rule will benefit public understanding of the law. As reflected in Section 6(a) of E.O. 13563, which requires agencies to engage in retrospective analyses of their rules “and to modify, streamline, expand, or repeal [such rules] in accordance with what has been learned,” removing an “outmoded” and “ineffective” rule from the Code of Federal Regulations is in the public interest.

Costs of the Final Rule

A detailed discussion of the costs of the final rule is included in the section on Regulatory Procedures, infra. In sum, the final rule will impose relatively modest administrative and other cost burdens for contractors to ensure a workplace free of sex-based discrimination.

The only new administrative burden the final rule will impose on contractors is the one-time cost of regulatory familiarization—the estimated time it takes to review and understand the instructions for compliance—calculated at $41,602,500, or $83 per contractor company, the first year.

The only other new costs of this rule that contractors may incur are the costs of pregnancy accommodations, which OFCCP calculates to be $9,671,000 annually or less, or a maximum of $19 per contractor company per year.

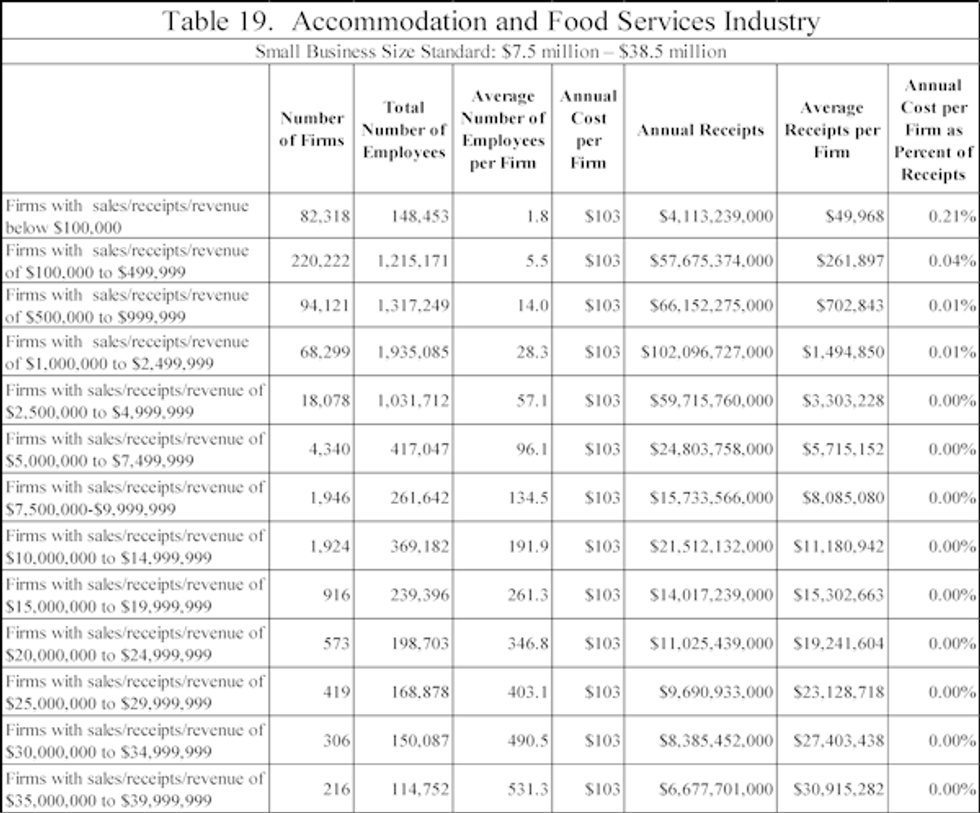

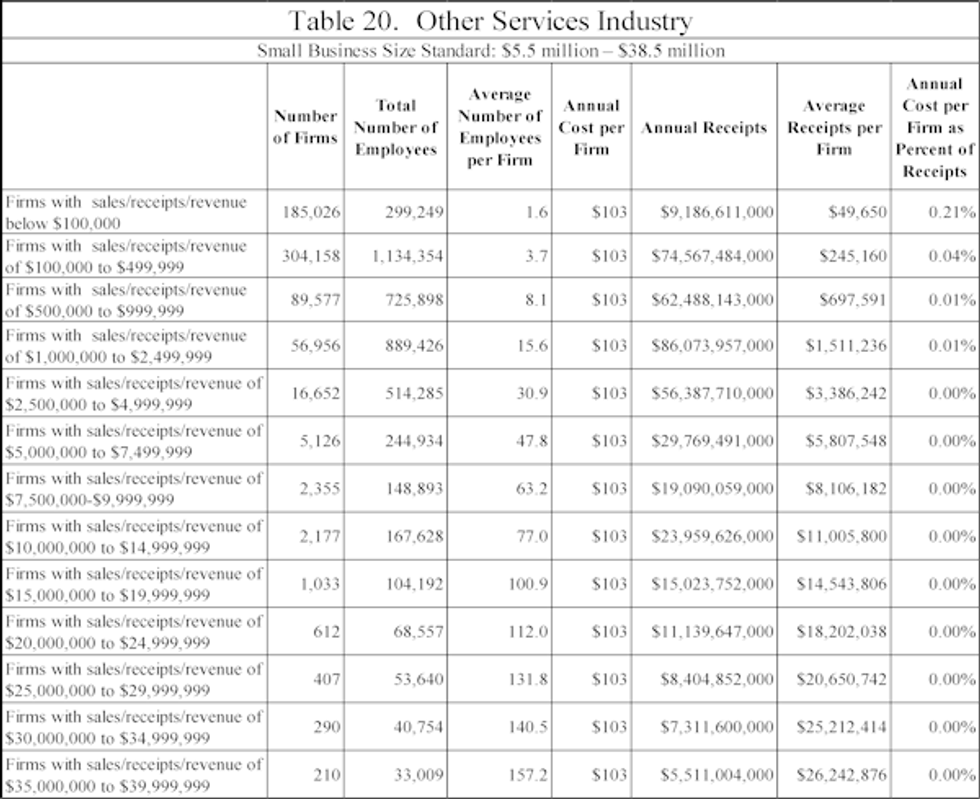

Together, these costs amount to a maximum of $51,273,500, or $103 per contractor company, in the first year, and a maximum of $9,671,000, or $19 per contractor company, each subsequent year. These costs are summarized in Table 1, “New Requirements,” infra.

Overview

Reasons for Promulgating This New Regulation

As described in the NPRM, since OFCCP's Sex Discrimination Guidelines were promulgated in 1970, there have been dramatic changes in women's participation in the workforce. Between 1970 and February, 2016, women's participation in the labor force grew from 43 percent to 57 percent.17 This included a marked increase of mothers in the workforce: The labor force participation of women with children under the age of 18 increased from 47 percent in 1975 to 70 percent in 2014.18 In 2014, both adults worked at least part time in 60 percent of married-couple families with children under 18, and 74 percent of mothers heading single-parent families with children under 18 worked at least part time.19

17 U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012, Table 588, Civilian Population—Employment Status by Sex, Race, and Ethnicity: 1970-2009, available at https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2011/compendia/statab/131ed/labor-force-employment-earnings.html (last accessed March 27, 2016) (1970 figure); Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor Statistics, Data Retrieval: Labor Force Statistics (Current Population Survey), Household Data, Table A-1, Employment status of the civilian population by sex and age, available at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t01.htm (last accessed March 25, 2016) (2016 figure).

18 Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, TED: The Economics Daily, Labor force participation rates among mothers, available at http://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2010/ted_20100507.htm (last accessed March 26, 2016) (1975 data); Press Release, Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Employment Characteristics of Families—2013 (April 23, 2015), available at http://www.bls.gov/news.release/famee.nr0.htm (last accessed February 21, 2016) (Employment Characteristics of Families—2014) (2014 data).

19 Employment Characteristics of Families—2014, supra note 18.

Since 1970, there have also been extensive changes in the law regarding sex-based employment discrimination and in contractor policies and practices governing workers. For example:

- Title VII, which generally governs the law of sex-based employment discrimination, has been amended four times: In 1972, by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act; 20 in 1978, by the PDA; in 1991, by the Civil Rights Act; 21 and in 2009, by the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act (FPA).22

20 Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Public Law 92-261, 86 Stat. 103 (1972).

21 Civil Rights Act of 1991, Public Law 102-166, 1745, 105 Stat. 1071 (1991).

22 Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, Public Law 111-2, 123 Stat. 5 (2009). - State “protective laws” that had explicitly barred women from certain occupations or otherwise restricted their employment conditions on the basis of sex have been repealed or are unenforceable.23

23 See, e.g., Conn. Gen. Stat. §31-18 (repealed 1973) (prohibition of employment of women for more than nine hours a day in specified establishments); Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 345 (1911) (repealed 1974) (outright prohibition of employment of women before and after childbirth); Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §4107.43 (repealed 1982) (prohibition of employment of women in specific occupations that require the routine lifting of more than 25 pounds); see also Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty, 434 U.S. 136, 142 (1977) (invalidating public employer requirement that pregnant employees take a leave of absence during which they did not receive sick pay and lost job seniority); Cleveland Bd. of Educ. v. LaFleur, 414 U.S. 632 (1974) (striking rules requiring leave from after the fifth month of pregnancy until three months after birth); Somers v. Aldine Indep. Sch. Dist., 464 F. Supp. 900 (S.D. Tex. 1979) (finding sex discrimination where school district terminated teacher for not complying with requirement that pregnant women take an unpaid leave of absence following their third month or be terminated). - In 1993, the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) 24 was enacted, requiring employers with 50 or more employees to provide a minimum of 12 weeks of annual, unpaid, job-guaranteed leave to both male and female employees to recover from their own serious health conditions (including pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions); to care for a newborn or newly adopted or foster child; or to care for a child, spouse, or parent with a serious health condition.

24 29 U.S.C. 2601 et seq. - In 1970, it was not uncommon for employers to require female employees to retire at younger ages than their male counterparts. However, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act was amended in 1986 to abolish mandatory retirement for all employees with a few exceptions.25

25 29 U.S.C. 621-634.

Moreover, since 1970, the Supreme Court has determined that numerous practices that were not then widely recognized as discriminatory constitute unlawful sex discrimination under title VII. See e.g., City of Los Angeles v. Manhart, 435 U.S. 702 (1978) (prohibiting sex-differentiated employee pension fund contributions, despite statistical differences in longevity); Cnty. of Washington v. Gunther, 452 U.S. 161 (1981) (holding that compensation discrimination is not limited to unequal pay for equal work within the meaning of the Equal Pay Act); Newport News Shipbldg. & Dry Dock Co. v. EEOC, 462 U.S. 669 (1983) (holding that employer discriminated on the basis of sex by excluding pregnancy-related hospitalization coverage for the spouses of male employees while providing complete hospitalization coverage for female employees, resulting in greater insurance coverage for married female employees than for married male employees); Meritor Sav. Bank v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57 (1986) (recognizing cause of action for sexually hostile work environment); Cal. Fed. Sav. & Loan Ass'n v. Guerra, 479 U.S. 272 (1987) (upholding California law requiring up to four months of job-guaranteed leave for pregnant employees and finding law not inconsistent with title VII); Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989) (finding sex discrimination on basis of sex stereotyping); Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Servs., 523 U.S. 75, 79 (1998) (recognizing cause of action for “same sex” harassment); Int'l Union, United Auto., Aerospace & Agric. Implement Workers of Am. v. Johnson Controls, Inc., 499 U.S. 187 (1991) (holding that possible reproductive health hazards to women of childbearing age did not justify sex-based exclusions from certain jobs); Burlington Indus., Inc. v. Ellerth, 524 U.S. 742 (1998), and Faragher v. City of Boca Raton, 524 U.S. 775 (1998) (holding employers vicariously liable under title VII for the harassing conduct of supervisors who create hostile working conditions for those over whom they have authority); Burlington N. & Santa Fe Ry. Co. v. White, 548 U.S. 53 (2006) (clarifying broad scope of prohibition of retaliation for filing charge of sex discrimination); and Young v. United Parcel Serv., Inc., 135 S. Ct. 1338 (2015) (Young v. UPS) (holding that the plaintiff created a genuine issue of material fact as to whether the employer accommodated others “similar in their ability or inability to work” when it did not provide light-duty accommodations for pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions, but did provide them for on-the-job injuries, disabilities within the meaning of the Americans with Disabilities Act,26 and loss of certain truck driver certifications).

26 Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. 12101 et seq., as amended (ADA).

In response to these legal and economic changes, the landscape of employment policies and practices has also changed. Contractors rarely adopt or implement explicit rules that prohibit hiring of women for certain jobs. Jobs are no longer advertised in sex-segregated newspaper columns. Women have made major inroads into professions and occupations traditionally dominated by men. For example, women's representation among doctors more than doubled, from approximately 16 percent in 1988 27 to 38 percent in 2015.28 Executive suites are no longer predominantly segregated by sex, with all the executive positions occupied by men while women work primarily as secretaries. Indeed, in 2015, women accounted for 39 percent of all managers.29 Moreover, the female-to-male earnings ratio for women and men working full-time, year-round in all occupations increased from 59 percent in 1970 to 79 percent in 2014.30

27 E. More, “The American Medical Women's Association and the role of the woman physician, 1915-1990,” 45 Journal of the American Medical Women's Association 165, 178 (1990), available at 95th Anniversary Commemorative Booklet, https://www.amwa-doc.org/about-amwa/history/ (last accessed March 17, 2016).

28 Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, Table 11, Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, Household Data Annual Averages, available at http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm (last accessed March 17, 2016) (BLS Labor Force Statistics 2015).

29 Id.

30 U.S. Census Bureau, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014, Current Population Reports 10 (2015) 41 (Table A-4, Number and Real Median Earnings of Total Workers and Full-Time, Year-Round Workers by Sex and Female-to-Male Earnings Ratio: 1960 to 2014), available at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-252.pdf (last accessed March 25, 2016) (Income and Poverty Report 2014).

Employer-provided insurance policies that provide lower-value or otherwise less comprehensive hospitalization or disability benefits for pregnancy-related conditions than for other medical conditions are now unlawful under title VII.31 Generous leave and other family-friendly policies are increasingly common. As early as 2000, even employers that were not covered by the FMLA routinely extended leave to their employees for FMLA-covered reasons: two-thirds of such employers provided leave for an employee's own serious health condition and for pregnancy-related disabilities, and half extended leave to care for a newborn child.32 In recent years, 13 percent of employees had access to paid family leave, and most employees received some pay during family and medical leave due to paid vacation, sick, or personal leave or temporary disability insurance.33

31 These practices, common before the PDA, were prohibited when the PDA became effective with respect to fringe benefits in 1979. As the EEOC explained in guidance on the PDA issued in 1979:

A woman unable to work for pregnancy-related reasons is entitled to disability benefits or sick leave on the same basis as employees unable to work for other medical reasons. Also, any health insurance provided must cover expenses for pregnancy-related conditions on the same basis as expenses for other medical conditions.

Appendix to Part 1604—Questions and Answers on the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, 44 FR 23805 (April 20, 1979), 29 CFR part 1604. EEOC's recently issued guidance echoes this earlier interpretation and discusses recent developments on benefits issues affecting PDA compliance. EEOC Enforcement Guidance: Pregnancy Discrimination and Related Issues I.C.2-4 (2015), available at http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/pregnancy_guidance.cfm (last accessed March 25, 2016) (EEOC Pregnancy Guidance).

32 Wage and Hour Division, U.S. Department of Labor, The 2000 Survey Report ch. 5, Table 5-1. Family and Medical Leave Policies by FMLA Coverage Status, 2000 Survey Report available at http://www.dol.gov/whd/fmla/chapter5.htm (last accessed March 25, 2016).

33 BLS, National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2015 (September 2015), Table 32. Leave benefits: Access, civilian workers, National Compensation Survey, March 2015, available at http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2015/ownership/civilian/table32a.pdf (last accessed February 19, 2016). In addition, in 2012, most employees taking family or medical leave had some access to paid leave: “48% Report[ed] receiving full pay and another 17% receive[d] partial pay, usually but not exclusively through regular paid vacation leave, sick leave, or other 'paid time off' hours.” Jacob Klerman, Kelly Daley, & Alyssa Pozniak, Family and Medical Leave in 2012: Executive Summary ii, http://www.dol.gov/asp/evaluation/fmla/FMLA-2012-Executive-Summary.pdf (last accessed March 27, 2016).

While these changes in policies and practices show a measure of progress, there is no doubt that sex discrimination remains a significant and pervasive problem. Many of the statistics cited above, while improvements to be sure, are far from evincing a workplace free of discrimination. Sex-based occupational segregation, wage disparities, discrimination based on pregnancy or family caregiving responsibilities, sex-based stereotyping, and sexual harassment remain widespread. Had the incidence of sex discrimination decreased, one would expect at least some decrease in the proportion of total annual EEOC charges that allege sex discrimination. But that proportion has remained nearly constant at around 30 percent since at least 1997.34

34 This rate has varied from a low of 28.5 percent in FY 2011 to a high of 31.5 percent in FY 2000. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Enforcement and Litigation Statistics, Charge Statistics: FY 1997 Through FY 2015, available at http://eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/charges.cfm (last accessed February 21, 2016) (EEOC Charge Statistics). In FY 2015, the EEOC received 26,396 charges alleging sex discrimination.

One commenter, who nevertheless supports the NPRM, points out that the number of sex discrimination charges filed with the EEOC “decreased by 2000 from 2010 to 2013.” It is true that the number of sex discrimination charges filed with the EEOC decreased during this particular time period (by 1342, not by 2000). However, the total number of charges filed decreased during this period (from 99,922 to 88,778), while the percentage of charges alleging sex discrimination increased, from 29.1 percent to 29.5 percent. Moreover, since 1997, the general trend in the raw number of sex discrimination charges filed has been upwards, from 24,728 in FY 1997 to 26,396 charges in FY 2015, with a high of 30,356 charges in FY 2012.

Sex-Based Occupational Discrimination

Sex-based occupational sex segregation remains widespread:

In 2012, nontraditional occupations for women employed only six percent of all women, but 44 percent of all men. The same imbalance holds for occupations that are nontraditional for men; these employ only 5 percent of men, but 40 percent of women. Gender segregation is also substantial in . . . broad sectors where men and women work: three in four workers in education and health services are women, nine in ten workers in the construction industry and seven in ten workers in manufacturing are men.35

35 Ariane Hegewisch & Heidi Hartmann, Institute for Women's Policy Research, Occupational Segregation and the Gender Wage Gap: A Job Half Done (2014), available at http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/occupational-segregation-and-the-gender-wage-gap-a-job-half-done (last accessed March 27, 2016) (citations omitted); see also Ariane Hegewisch et al., The Gender Wage Gap by Occupation, Fact Sheet #C350a, The Institute for Women's Policy Research, available at http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/the-gender-wage-gap-by-occupation-2/at_download/file/ (last accessed March 25, 2016) (IWPR Wage Gap by Occupation).

OFCCP has found unlawful discrimination in the form of sex-based occupational segregation in several compliance evaluations of Federal contractors.36 For example, OFCCP recently found evidence that a call center steered women into lower-paying positions that assisted customers with cable services rather than higher-paying positions providing customer assistance for Internet services because the latter positions were considered “technical”; 37 that a sandwich production plant steered men into dumper/stacker jobs and women into biscuit assembler jobs, despite the fact that the positions required the same qualifications; 38 and that a parking company steered women into lower-paying cashier jobs and away from higher-paying jobs as valets.39 The EEOC and at least one court have found discrimination in similar cases as well.40

36 The contractors that OFCCP reviewed did not admit that they engaged in unlawful discrimination.

37 OFCCP Press Release, “Comcast Corporation settles charges of sex and race discrimination” (April 30, 2015), available at http://www.dol.gov/opa/media/press/ofccp/OFCCP20150844.htm (last accessed March 25, 2016).

38 OFCCP Press Release, “Hillshire Brands Co.'s Florence, Alabama, production plant settles charges of sex discrimination with US Labor Department” (September 18, 2014), available at http://www.dol.gov/opa/media/press/ofccp/OFCCP20141669.htm (last accessed March 25, 2016).

39 OFCCP Press Release, “Central Parking System of Louisiana Inc. settles hiring and pay discrimination case with US Department of Labor” (September 4, 2014), available at http://www.dol.gov/opa/media/press/ofccp/OFCCP20140920.htm (last accessed March 25, 2016).

40 See, e.g., EEOC v. New Prime, Inc., 42 F. Supp. 3d 1201 (W.D. Mo. 2014) (ruling that a trucking company discriminated against female truck driver applicants in violation of title VII by requiring that they be trained by female trainers, of whom there were very few); EEOC Press Release, “Mavis Discount Tire to Pay $2.1 Million to Settle EEOC Class Sex Discrimination Lawsuit” (March 25, 2016), available at http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/release/3-25-16.cfm (last accessed April 4, 2016) (EEOC alleged that tire retailer refused to hire women as managers, assistant managers, mechanics, and tire technicians); EEOC Press Release, “Merrilville Ultra Foods to Pay $200,000 to Settle EEOC Sex Discrimination Suit” (July 10, 2015), available at http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/release/7-10-15c.cfm (last accessed April 4, 2016) (EEOC alleged that grocer refused to hire women for night-crew stocking positions); EEOC Press Release, “Unit Drilling to Pay $400,000 to Settle EEOC Systemic Sex Discrimination Suit” (April 22, 2015), available at http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/release/4-22-15a.cfm (last accessed April 4, 2016) (EEOC alleged that oil drilling company refused to hire women on its oil rigs).

Sex discrimination and other barriers in the construction trades, on the part of both trade unions and employers, remain a particularly intractable problem. Several commenters described many “barriers for women and girls attempting to access [construction careers] and thrive” in them, both on the job and in apprenticeship programs: gender stereotyping; discrimination in hiring, training, and work and overtime assignments; hostile workplace practices and sexual harassment; insufficient training and instruction; and worksites that fail to meet women's basic needs. One commenter, a female worker in a construction union, recounted “discrimination and sexual harassment so bad” at the construction site that she had to quit. In 2014, OFCCP found sex discrimination by a construction contractor in Puerto Rico that involved several of these barriers: Denial of regular and overtime work hours to female carpenters comparable to those of their male counterparts, sexual harassment of the women, and failure to provide restroom facilities.41

41 OFCCP Press Release, “Puerto Rico construction contractor settles sexual harassment and discrimination case with US Department of Labor” (April 2, 2014), available at http://www.dol.gov/opa/media/press/ofccp/OFCCP20140363.htm (last accessed March 25, 2016).

Likewise, women continue to be underrepresented in higher-level and more senior jobs within occupations. For example, in 2015, women accounted for only 28 percent both of chief executive officers and of general/operations managers.42

42 BLS Labor Force Statistics 2015, supra note 28.

Wage Disparities

As mentioned above, in 2014, women working full time earned 79 cents on the dollar compared to men, measured on the basis of median annual earnings.43 While this represents real progress from the 59 cents on the dollar measured in 1970, the size of the gap is still unacceptable, particularly given that the Equal Pay Act was enacted over 50 years ago. In fact, it appears that the narrowing of the pay gap has slowed since the 1980's.44 At the rate of progress from 1960 to 2011, researchers estimated it would take until 2057 to close the gender pay gap.45

43 Income and Poverty Report 2014, supra note 30.

44 From 1980 to 1989, the percentage of women's earnings relative to men's increased from 60.2 percent to 68.7 percent; from 1990 to 1999, the percentage increased from 71.6 percent to just 72.3 percent; and from 2000 to 2009, the percentage increased from 76.9 percent to 78.6 percent. Id. See also Youngjoo Cha & Kim A. Weeden, Overwork and the Slow Convergence in the Gender Gap in Wages, Am. Soc. Rev. 1 (2014), available at http://www.asanet.org/journals/ASR/ChaWeedenJune14ASR.pdf (last accessed March 25, 2016); Francine D. Blau & Lawrence M. Kahn, The U.S. Gender Pay Gap in the 1990s: Slowing Convergence, 60 Indus. & Lab. Rel. Rev. 45 (2006) (Slowing Convergence).

45 Institute for Women's Policy Research, At Current Pace of Progress, Wage Gap for Women Expected to Close in 2057 (April 2013), available at http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/at-current-pace-of-progress-wage-gap-for-women-expected-to-close-in-2057 (last accessed March 25, 2016).

The wage gap is also greater for women of color and women with disabilities. When measured by median full-time annual earnings, in 2014 African-American women made approximately 60 cents and Latinas made approximately 55 cents for every dollar earned by a non-Hispanic, white man.46 In 2014, median annual earnings for women with disabilities were only 47 percent of median annual earnings for men without disabilities.47

46 Calculations from U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Income Tables: People, Table P-38, Full-Time, Year-Round Workers by Median Earnings and Sex, available at https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/people/ (last accessed February 22, 2016).

47 Calculation from U.S. Census Bureau, American Fact Finder, “Median earnings in the past 12 months (in 2014 inflation-adjusted dollars) by disability status by sex for the civilian noninstitutionalized population 16 years and over with earnings, 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates” available at http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_13_1YR_B18140&prodType=table (last accessed March 25, 2016).

Of course, discrimination may not be the cause of the entire gap; these disparities can be explained to some extent by differences in experience, occupation, and industry.48 However, decades of research show these wage gaps remain even after accounting for factors like the types of work people do and qualifications such as education and experience.49 Moreover, while some women may work fewer hours or take time out of the workforce because of family responsibilities, research suggests that discrimination and not just choices can lead to women with children earning less; 50 to the extent that the potential explanations such as type of job and length of continuous labor market experience are also influenced by discrimination, the “unexplained” difference may understate the true effect of sex discrimination.51

48 Equal Pay for Equal Work? New Evidence on the Persistence of the Gender Pay Gap: Hearing Before United States Joint Economic Comm., Majority Staff of the Joint Econ. Comm., 111th Cong., Invest in Women, Invest in America: A Comprehensive Review of Women in the U.S. Economy 78, 81-82 (Comm. Print 2010), available at http://jec.senate.gov/public/?a=Files.Serve&File_id=9118a9ef-0771-4777-9c1f-8232fe70a45c (last accessed March 25, 2016) (statement of Randy Albelda, Professor of Economics and Senior Research Associate, University of Massachusetts—Boston Center for Social Policy) (Equal Pay for Equal Work?).

49 A 2011 White House report found that while earnings for women and men typically increase with higher levels of education, a male-female pay gap persists at all levels of education for full-time workers (35 or more hours per week), according to 2009 BLS wage data. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, and Executive Office of the President, Office of Management and Budget, Women in America: Indicators of Social and Economic Well-Being 32 (2011), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/rss_viewer/Women_in_America.pdf (last accessed March 25, 2016). As noted above, potentially nondiscriminatory factors can explain some of the gender wage differences; even so, after controlling for differences in skills and job characteristics, women still earn less than men. Equal Pay for Equal Work?, supra note 48, at 80-82. Ultimately, the research literature still finds an unexplained gap exists even after accounting for potential explanations and finds that the narrowing of the pay gap for women has slowed since the 1980s. Joyce P. Jacobsen, The Economics of Gender 44 (2007); Slowing Convergence, supra note 44.

50 Shelley J. Correll, Stephen Benard, & In Paik, Getting a Job: Is There a Motherhood Penalty? 112 American Journal of Sociology 1297, 1334-1335 (2007), available at http://gender.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/motherhoodpenalty.pdf (last accessed March 25, 2016) (Motherhood Penalty).

51 Strengthening the Middle Class: Ensuring Equal Pay for Women: Hearing Before H. Comm. on Educ. and Labor, 110th Cong. (2007), available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-110hhrg34632/html/CHRG-110hhrg34632.htm (last accessed March 25, 2016) (statement of Heather Boushey, Senior Economist, Center for Economic and Policy Research) (“there are many aspects of women's employment patterns and pay that cannot reasonably be attributed to choice”).

Male-dominated occupations generally pay more than female-dominated occupations at similar skill levels. But even within the same occupation, women earn less than men on average. For example, in 2012, full-time earnings for female auditors and accountants were less than 74 percent of the earnings of their male counterparts.52 Among the 20 most common occupations for women, the occupation of retail sales faced the largest wage gap; women in this occupation earned only 64 percent of what men earned.53 Likewise, in the medical profession, women earn less than their male counterparts. On average, male physicians earn 13 percent more than female physicians at the outset of their careers, and as much as 28 percent more eight years later.54 This gap cannot be explained by practice type, work hours, or other characteristics of physicians' work.55

52 IWPR Wage Gap by Occupation, supra note 35, at 2.

53 Id.

54 Constanca Esteves-Sorenson & Jason Snyder, The Gender Earnings Gap for Physicians and Its Increase over Time 4 (2011), available at http://faculty.som.yale.edu/ConstancaEstevesSorenson/documents/Physician_000.pdf (last accessed March 25, 2016).

55 Id. A 2008 study on physicians leaving residency programs in New York State also found a $16,819 pay gap between male and female physicians. Anthony T. LoSasso, Michael R. Richards, Chiu-Fang Chou & Susan E. Gerber, The $16,819 Pay Gap For Newly Trained Physicians: The Unexplained Trend Of Men Earning More Than Women, 30 Health Affairs 193 (2011), available at http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/30/2/193.full.pdf html (last accessed March 25, 2016).

Discrimination Based on Pregnancy or Family Caregiving Responsibilities

Despite enactment of the PDA, women continue to report that they have experienced discrimination on account of pregnancy. Between FY 1997 and FY 2011, the number of charges of pregnancy discrimination filed with the EEOC and state and local agencies annually was significant, ranging from a low of 3,977 in 1997 to a high of 6,285 in 2008.56 The Chair of the EEOC recently testified before a Congressional committee:

56 EEOC, Pregnancy Discrimination Charges, EEOC & FEPAs Combined: FY 1997-FY 2011, available at http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/pregnancy.cfm (last accessed March 16, 2017). FY 2011 is the last year for which comparable data are available. For each of the years FY 2012-FY 2015, four percent of the charges filed with the EEOC alleged pregnancy discrimination. OFCCP calculations made from data from EEOC, Pregnancy Discrimination Charges, FY 2010-FY 2015, available at http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/pregnancy_new.cfm (last accessed March 17, 2016), and EEOC Charge Statistics, supra note 34.

Still today, when women become pregnant, they continue to face harassment, demotions, decreased hours, forced leave, and even job loss. In fact, approximately 70 percent of the thousands of pregnancy discrimination charges EEOC receives each year allege women were fired as a result of their pregnancy.57

57 Testimony of EEOC Chair Jenny Yang Before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions 4 (May 19, 2015), available at http://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Yang.pdf (last accessed March 25, 2016) (Yang Testimony).

Low-income workers, in particular, face “extreme hostility to pregnancy.” 58

58 Stephanie Bornstein, Center for WorkLife Law, UC Hastings College of the Law, Poor, Pregnant and Fired: Caregiver Discrimination Against Low-Wage Workers 2 (2011), available at http://worklifelaw.org/pubs/PoorPregnantAndFired.pdf (last accessed March 27, 2016).

One commenter provides examples of recent cases to illustrate the prevalence of discrimination against women who are breastfeeding. In one, Donnicia Venters lost her job after she disclosed to her manager that she was breastfeeding and would need a place to pump breast milk.59 In another, Bobbi Bockoras alleged she was forced to pump breast milk under unsanitary or insufficiently private conditions, harassed, and subjected to retaliation.60

59 See EEOC v. Houston Funding II, Ltd., 717 F.3d 425, 427 (5th Cir. 2013) (reversing summary judgment for defendant and holding that discrimination on the basis of lactation is sex discrimination under title VII).

60 See Amended Complaint, Bockoras v. St. Gobain Containers, No. 1:13-cv-0334, Document No. 44 (W.D. Pa. March 6, 2014). The commenter reported that the company denied the allegations, but the case settled.

In addition, some workers affected by pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions face a serious and unmet need for workplace accommodations, which are often vital to their continued employment and, ultimately, to their health and that of their children. OFCCP is aware of a number of situations in which women have been denied accommodations with deleterious health consequences. For example:

In one instance, a pregnant cashier in New York who was not allowed to drink water during her shift, in contravention of her doctor's recommendation to stay well-hydrated, was rushed to the emergency room after collapsing at work. As the emergency room doctor who treated her explained, because “pregnant women are already at increased risk of fainting (due to high progesterone levels causing blood vessel dilation), dehydration puts them at even further risk of collapse and injury from falling.” Another pregnant worker was prohibited from carrying a water bottle while stocking grocery shelves despite her doctor's instructions that she drink water throughout the day to prevent dehydration. She experienced preterm contractions, requiring multiple hospital visits and hydration with IV fluids. . . . [Another] woman, a pregnant retail worker in the Midwest who had developed a painful urinary tract infection, supplied a letter from her doctor to her employer explaining that she needed a short bathroom break more frequently than the store's standard policy. The store refused. She later suffered another urinary tract infection that required her to miss multiple days of work and receive medical treatment.61

61 Brief of Health Care Providers, the National Partnership for Women & Families, and Other Organizations Concerned with Maternal and Infant Health as Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioner in Young v. United Parcel Service, at 9-10, 11 (citations omitted), available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/supreme_court_preview/BriefsV4/12-1226_pet_amcu_hcp-etal.authcheckdam.pdf (last accessed March 25, 2016). See also Wiseman v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., No. 08-1244-EFM, 2009 WL 1617669 (D. Kan. June 9, 2009) (pregnant retail employee with recurring urinary and bladder infections caused by dehydration alleged she was denied permission to carry a water bottle despite doctor's note), available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCOURTS-ksd-6_08-cv-01244/pdf/USCOURTS-ksd-6_08-cv-01244-0.pdf (last accessed March 27, 2016).

In one comment submitted on the NPRM, three organizations that provide research, policy, advocacy, or consulting services to promote workplace gender equality and work-life balance for employees state that they “have seen numerous . . . cases where women are pushed out of work simply because they wish to avoid unnecessary risks to their pregnancy” when doctors advise them to avoid exposure to toxic chemicals, dangerous scenarios, or physically strenuous work to prevent problems from occurring in their pregnancies. “Pregnant workers in physically demanding, inflexible, or hazardous jobs are particularly likely to need accommodations at some point during their pregnancies to continue working safely.” 62

62 National Women's Law Center & A Better Balance, It Shouldn't Be a Heavy Lift: Fair Treatment for Pregnant Workers 5 (2013), available at http://www.nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/pregnant_workers.pdf (last accessed March 25, 2016) (Heavy Lift).

Meanwhile, more women today continue to work throughout their pregnancies and therefore are more likely to need accommodations of some sort. Of women who had their first child between 1966 and 1970, 49 percent worked during pregnancy; of those, 39 percent worked into the last month of their pregnancy. For the period from 2006 to 2008, the proportion of pregnant women working increased to 66 percent, and the proportion of those working into the last month of their pregnancy increased to 82 percent.63

63 U.S. Census Bureau, Maternity Leave and Employment Patterns of First-Time Mothers: 1961-2008, at 4, 7 (2011), available at http://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p70-128.pdf (last accessed March 25, 2016) (tables 1 and 3).

Several commenters provided evidence of continued discriminatory practices in the provision of family or medical leave. One explained that “[w]orkplaces routinely offer fewer weeks of ‘paternity’ leave than ‘maternity’ leave” and that such policies “can be particularly detrimental to LGBT [lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender] people, who are more likely to be adoptive parents and, as such, may not be able to access traditional ‘maternity’ leave frequently reserved for workers who have given birth to a child.” Another, a provider of legal services to low-income clients, stated that “[l]ow wage workers are often put on leave before they want or need it” and that such workers, “when not covered by FMLA, . . . are frequently denied leave despite a disparate impact based on gender without business necessity.”

Sexual Harassment

The EEOC adopted sexual harassment guidelines in 1980, and the Supreme Court held that sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination in 1986.64 Nevertheless, as several commenters report, sexual harassment continues to be a serious problem for women in the workplace and a significant barrier to women's entry into and advancement in many nontraditional occupations, including the construction trades 65 and the computer and information technology industries.66 In fact, in FY 2015, the EEOC received 6,822 sexual harassment charges—7.6 percent of the total of 89,385 charges filed.67 This percentage is hardly different from FY 2010, when the number of sexual harassment charges the EEOC received was 8.0 percent of the total charges filed.68

64 EEOC Guidelines on Discrimination Because of Sex, 29 CFR 1604.11 (1980), available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2014-title29-vol4/xml/CFR-2014-title29-vol4-part1604.xml (last accessed March 25, 2016) (provision on harassment); Meritor Sav. Bank v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57 (1986). The Court reaffirmed and extended that holding in 1993. Harris v. Forklift Sys., 510 U.S. 17 (1993). Lower courts had held that sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination since the late 1970s. See, e.g., Barnes v. Costle, 561 F.2d 983 (D.C. Cir. 1977).

65 See National Women's Law Center, Women in Construction: Still Breaking Ground 8 (2014), available at http://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/final_nwlc_womeninconstruction_report.pdf (last accessed March 17, 2016).

66 See Women in Tech, Elephant in the Valley (2016), http://elephantinthevalley.com/ (last accessed March 16, 2016) (60% of respondents to survey of women who worked in the technology industry experienced unwanted sexual advances).

67 EEOC, Enforcement & Litigation Statistics, Sexual Harassment Charges FY 2010-2015, available at http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/sexual_harassment_new.cfm (last accessed March 17, 2016); EEOC Charge Statistics, supra note 34.

68 Id.

Sex-Based Stereotyping

In some ways, the nature of sex discrimination has also changed since OFCCP promulgated the Sex Discrimination Guidelines. Explicit sex segregation, such as facial “male only” hiring policies, has been replaced in many workforces by less overt mechanisms that nevertheless present real equal opportunity barriers.

One of the most significant barriers is sex-based stereotyping. Decades of social science research have documented the extent to which sex-based stereotypes about the roles of women and men and their respective capabilities in the workplace can influence decisions about hiring, training, promotions, pay raises, and other conditions of employment.69 As the Supreme Court recognized in 1989, an employer engages in sex discrimination where the likelihood of promotion for female employees depends on whether they fit their managers' preconceived notions of how women should dress and act.70 Research clearly demonstrates that widely held social attitudes and biases can lead to discriminatory decisions, even where there is no formal sex-based (or race-based) policy or practice in place.71 One commenter on the NPRM highlights a study showing, through both a laboratory experiment and a paired-resume audit, that stereotypes about caregiving responsibilities affect women's employment opportunities significantly. In the experimental study, only 47 percent of mothers were recommended for hire, compared to 84 percent of female non-mothers (i.e., non-mothers were recommended for hire 1.8 times more frequently than mothers); mothers were offered starting salaries $11,000 (7.4 percent) less than those offered to non-mothers; mothers were less likely to be recommended for promotion to management positions; and being a parent lowered the competence ratings for women but not for men. In the audit, non-mothers received 2.1 times as many call-backs as equally qualified mothers.72 Sex-based stereotyping may have even more severe consequences for transgender, lesbian, gay, and bisexual applicants and employees, many of whom report that they have experienced discrimination in the workplace.73

69 See, e.g., Susan Fiske et al., Controlling Other People: The Impact of Power on Stereotyping, 48 a.m. Psychol. 621 (1993), available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/14870029_Controlling_Other_People_The_Impact_of_Power_on_Stereotyping (last accessed March 27, 2016); Anthony Greenwald and Mahzarin Banaji, Implicit Social Cognition: Attitudes, Self-Esteem and Stereotypes, 102 Psychol. Rev. 4 (1995); Brian Welle & Madeline Heilman, Formal and Informal Discrimination Against Women at Work, in Managing Social and Ethical Issues in Organizations 23 (Stephen Gilliland, Dirk Douglas Steiner & Daniel Skarlicki eds., 2007); Susan Bruckmüller, Michelle Ryan, Floor Rink, and S. Alexander Haslam, Beyond the Glass Ceiling: The Glass Cliff and Its Lessons for Organizational Policy, 8 Soc. Issues & Pol. Rev. 202 (2014) (describing the role of sex-based stereotypes in the workplace).

70 Price Waterhouse, 490 U.S. at 235, 250-51. Men, too, can experience adverse effects from sex-based stereotyping.

71 See, e.g., Kevin Lang & Jee-Yeon K. Lehmann, Racial Discrimination in the Labor Market: Theory and Empirics (NBER Working Paper No. 17450, 2010), available at http://www.nber.org/papers/w17450 (last accessed March 27, 2016); Marianne Bertrand & Sendhil Mullainathan, Are Emily and Brendan More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination, 94(4) American Econ. Rev. (2004); Ian Ayres & Peter Siegelman, Race and Gender Discrimination in Bargaining for a New Car, 85(3) Am. Econ. Rev. (1995); Marc Bendick, Charles Jackson & Victor Reinoso, Measuring Employment Discrimination Through Controlled Experiments, 23 Rev. of Black Pol. Econ. 25 (1994).

One commenter expressed concern that this statement, which was made originally in the NPRM, demonstrates an OFCCP enforcement approach contrary to Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, 131 S. Ct. 2541 (2011). Although the plaintiffs in Wal-Mart raised sex discrimination claims under title VII, the Supreme Court's decision was based on plaintiffs' failure to satisfy procedural requirements under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) regarding class action lawsuits. Unlike private plaintiffs, who must prevail on class certification motions to bring suit on behalf of others, OFCCP is a governmental agency that is authorized to act in the public's interest to remedy discrimination. It is not subject to the limitations and requirements of class certification under the FRCP. To the extent that the Supreme Court's decision in Wal-Mart addresses title VII principles that apply outside the context of class certification, OFCCP follows those principles in its enforcement of Executive Order 11246.

72 Motherhood Penalty, supra note 50, at 1316, 1318, 1330.

73 Injustice at Every Turn, supra note 16; Center for American Progress and Movement Advancement Project, Paying an Unfair Price: The Financial Penalty for Being LGBT in America 18-19 (September 2014; updated November 2014), available at http://www.lgbtmap.org/policy-and-issue-analysis/unfair-price (last accessed March 27, 2016) (discussing studies showing LGBT-based employment discrimination); Brad Sears & Christy Mallory, The Williams Institute, Documented Evidence of Employment Discrimination & Its Effects on LGBT People (2011), available at http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Sears-Mallory-Discrimination-July-20111.pdf (last accessed March 27, 2016). Further discussion of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity can be found infra in the passages on paragraph 60-20.2(a) and §60-20.7.

In sum, with the marked increase of women in the labor force, the changes in employment practices, and numerous key legal developments since 1970, many of the provisions in the Guidelines are outdated, inaccurate, or both. At the same time, there are important and current areas of law that the Guidelines fail to address at all. For those reasons, OFCCP is replacing the Guidelines with a new final rule that addresses these changes.

Overview of the Comments

Prior to issuing an NPRM, OFCCP consulted a small number of individuals from the contractor community, women's groups, and other stakeholders to understand their views on the provisions in the Sex Discrimination Guidelines, specifically which provisions should be removed, updated, or added. There was substantial overlap in opinion among these experts about these matters. In particular, they stated that the second sentence in §60-20.3(c) of the Guidelines, addressing employer contributions for pensions and other fringe benefits, is an incorrect statement of the law; that the references to State “protective” laws in §60-20.3(f) of the Guidelines are outmoded; that §60-20.3(g) of the Guidelines, concerning pregnancy, should be updated to reflect the PDA; and that the reference to the Wage and Hour Administrator in §60-20.5(c) of the Guidelines should be removed, as the Wage and Hour Administrator no longer enforces the Equal Pay Act.

OFCCP received 553 comments on the NPRM. They include 445 largely identical form-letter comments from 444 individuals expressing general support, apparently as part of an organized comment-writing effort.74 The 108 remaining comments, representing diverse perspectives, include comments filed by one small business contractor; one construction contractor; two law firms representing contractors; three contractor associations; four associations representing employers (including contractors); one contractor consultant; 23 civil rights, women's, and LGBT organizations; one union; a provider of legal services to low-income individuals; one religious organization; a state credit-union association that has 400 credit-union members; and many individuals.

74 One of these individuals submitted virtually identical comments twice.

Many additional organizations express their views by signing on to comments filed by other organizations, rather than by separately submitting comments.75 For example, 70 national, regional, state, and local women's, civil rights, LGBT, and labor organizations and coalitions of such organizations, all co-sign one comment filed by a women's organization. Similarly, three major organizations representing employers join a comment filed by one of them. Altogether, 101 unique organizations file or join comments generally supportive of the rule; 14 unique organizations file or join comments generally opposed to the rule.76

75 The result is that eight comments are co-signed by multiple organizations.

76 For this count, OFCCP includes state and regional chapters and affiliates of national organizations individually as commenters, separate from those national organizations.

The commenters raise a range of issues. Among the common or significant suggestions are those urging OFCCP:

- To add sexual orientation discrimination as a form of sex discrimination;

- to prohibit single-user restrooms from being segregated by sex;

- to clarify application of the BFOQ defense to gender identity discrimination;

- to require contractor-provided health insurance to cover gender-transition-related health care;

- to clarify that contractors' good faith affirmative action efforts after identifying underrepresentation of women in job groups are not inconsistent with the final rule;

- to specify factors that are legitimate for the purposes of setting pay;

- to remove the requirements that contractor-provided health insurance cover contraception and abortion (where the life of the mother would be endangered if the fetus were carried to term or medical complications have arisen from an abortion), and further arguing that application of some provisions in the proposed rule to contractors with religious objections are contrary to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA);

- to clarify application of Young v. UPS, supra, to the section addressing pregnancy-related accommodations;

- to require reasonable accommodation for pregnancy as a form of affirmative action;

- to clarify the relationship of FMLA leave to any leave that may be required by this rule;

- to add language concerning vicarious liability and negligence involving sexual harassment perpetrated by lower-level supervisors; and

- to add various examples of disparate-treatment or disparate-impact discrimination to the examples in the NPRM.

OFCCP's responses to these comments are discussed in connection with the relevant sections in the Section-by-Section Analysis.

There were also comments associated with the cost and burden of the proposed rule. OFCCP's responses to these comments are discussed in the section on Regulatory Procedures.

OFCCP carefully considered all of the comments in development of this final rule. In response to comments, or in order to clarify and focus the scope of one or more provisions while not increasing the estimated burden, the final rule revises some of the NPRM's provisions.

Overview of the Final Rule

Like the proposed rule, the final rule is organized quite differently than the Guidelines. One change is that while discussion of the BFOQ defense was repeated in several different sections of the Guidelines, the final rule consolidates this discussion into one section covering BFOQs.

Another major change is the reorganization of §60-20.2 in the Guidelines, which addressed recruitment and advertisement. Guidelines paragraph 60-20.2(a), which required recruitment of men and women for all jobs unless sex is a BFOQ, is subsumed in §60-20.2 of the final rule, which states and expands on the general principle of nondiscrimination based on sex and sets forth a number of examples of discriminatory practices. Guidelines paragraph 60-20.2(b) prohibited “[a]dvertisement in newspapers and other media for employment” from “express[ing] a sex preference unless sex is a bona fide occupational qualification for the job.” This statement does not have much practical effect, because few job advertisements today express a sex preference. It is therefore omitted from the final rule. Recruitment for individuals of a certain sex for particular jobs, including recruitment by advertisement, is covered in final rule paragraph 60-20.2(b)(10).

A third major change is the reorganization of §60-20.3 in the Guidelines. Entitled “Job policies and practices,” this section addressed a contractor's general obligations to ensure equal opportunity in employment on the basis of sex (Guidelines paragraphs 60-20.3(a), 60-20.3(b), and 60-20.3(c)); examples of discriminatory treatment (Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(d)); the provision of physical facilities, including bathrooms (Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(e)); the impact of state protective laws (Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(f)); leave for childbearing (Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(g)); and specification of retirement age (Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(h)). Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(i) stated that differences in capabilities for job assignments among individuals may be recognized by the employer in making specific assignments.

As mentioned above, the final rule relocates the general obligation to ensure equal employment opportunity and the examples of discriminatory practices to §60-20.2. Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(e), regarding gender-neutral provision of physical facilities, is now addressed in paragraphs 60-20.2(b)(12) and (13) and 60-20.2(c)(2) of the final rule. Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(f), addressing state protective laws, is not included in the final rule because it is unnecessary and anachronistic. The example at paragraph 60-20.2(b)(8) in the final rule, prohibiting sex-based job classifications, clearly states the underlying principle that absent a job-specific BFOQ, no job is the separate domain of any sex.77

77 One comment discusses the issue of state protective laws. It agrees with OFCCP's view that the provision is unnecessary and anachronistic, because “45 years of history have made clear that [state protective] laws violate Title VII and EO 11246 as amended.” See Int'l Union, United Auto., Aerospace & Agric. Implement. Workers of Am. v. Johnson Controls, Inc., 499 U.S. 187 (1991) (holding that possible reproductive health hazards to women of childbearing age did not justify sex-based exclusions from certain jobs).

Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(g), regarding leave for childbearing, is now addressed in §60-20.5 of the final rule on discrimination on the basis of pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions. Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(h), which prohibited differential treatment between men and women with regard to retirement age, is restated and broadened in the final rule, at paragraph 60-20.2(b)(7); it prohibits the imposition of sex-based differences not only in retirement age but also in “other terms, conditions, or privileges of retirement.” Guidelines paragraph 60-20.3(i) stated that the Sex Discrimination Guidelines allowed contractors to recognize differences in capabilities for job assignments in making specific assignments and reiterated that the purpose of the Guidelines was “to insure that such distinctions are not based upon sex.” This paragraph is omitted from the final rule because it is unnecessary and because its second sentence is repetitive of §60-20.1 in the final rule. Implicit in the provisions prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex is the principle that distinctions for other reasons, such as differences in capabilities, are not prohibited. Distinguishing among employees based on their relevant job skills, for example, does not constitute unlawful discrimination.

Where provisions of the Guidelines are uncontradicted by the final rule but are omitted from it because they are, as a practical matter, outdated, their omission does not mean that they are not still good law. For example, the prohibition of sex-specific advertisements in newspapers and other media in Guidelines paragraph 60-20.2(b) remains a correct statement of the law.

Comments on Language Usage Throughout the Rule

A number of commenters make recommendations about the language that OFCCP should use throughout the rule. Two commenters suggest that the rule should refer to “gender discrimination” instead of “sex discrimination.” OFCCP follows Title VII case law in interpreting “sex” discrimination to include gender discrimination.78 The NPRM used the word “sex” when referring to sex discrimination because “sex” is used in E.O. 11246, and the word “gender” in the phrase “gender identity” because “gender” is used in E.O. 13672. For these reasons, except where quoting or paraphrasing comments or references that use the terms differently, the final rule continues that usage.

78 Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228, 250 (1989) (“In the context of sex stereotyping, an employer who acts on the basis of a belief that a woman cannot be aggressive, or that she must not be, has acted on the basis of gender.”); see, e.g., Smith v. City of Salem, 378 F. 3d 566, 572 (6th Cir. 2004).

Three comments (joined by four commenters) recommend that phrases such as “he or she” and “his or her” be replaced with gender-neutral language such as “they” and “their” in order to recognize that some gender-nonconforming individuals prefer not to be identified with either gender. OFCCP declines to make this change. While it acknowledges that grammatical rules on this point may evolve, OFCCP believes it would be less confusing to a lay reader to use the more commonly understood formulations “he or she” and “him or her,” rather than a singular “they.” However, in a number of places in the rule and preamble, OFCCP replaces the singular “he or she” forms of pronouns with the plural “they” forms where it is possible to make all the references in the sentence plural. For instance, the example of sex stereotyping in §60-20.7(b) now reads: “Adverse treatment of employees or applicants for employment because of their actual or perceived gender identity or transgender status” (emphasis added), rather than “Adverse treatment of an employee or applicant for employment because of his or her actual or perceived gender identity or transgender status.” Where “his or her” or similar language does appear, it should be read to encompass people who do not identify as either gender.