Employers are generally prohibited from interfering with employee FMLA rights and from retaliating against employees for exercising those rights.

All covered employers are to post the FMLA general notice (poster), entitled “Employee Rights Under the Family and Medical Leave Act.” This is to be posted in a location where all employees and job applicants can clearly see it.

Employer coverage

- The FMLA covers private employers and public agencies that meet certain criteria.

Both private employers and public agencies can be covered by the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA).

If the company is a public agency, it doesn’t matter how many people it employs. Public agencies include the government of the United States; the government of a State or political subdivision thereof; any agency of the United States (including the United States Postal Service and Postal Rate Commission), a State, or a political subdivision of a State, or any interstate governmental agency.

If the company is in the private sector, it is covered if it has 50 or more employees for each working day during each of 20 or more calendar workweeks in the current or preceding calendar year.

State laws

Many states have laws that entitle employees to leave for various reasons. The laws also vary in relation to covered employers, eligible employees, how much leave, benefit protections, and so on. Reasons for leave under state laws can include, for example, leave for new parents, for domestic violence/victims, for pregnancy disability, for organ or bone marrow donation, military family, to care for more family members than the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) includes, public health emergencies, and child bereavement. Some state laws provide for paid leave for various reasons.

Integrated employers

- An “integrated employer” test can determine if separate entities can be designated as a single employer for FMLA purposes.

There are circumstances where the relationship between two entities is so close that the relationship is treated as being an integrated employer, and therefore treated as a single employer in counting employees for Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) coverage.

Separate entities can be designated as a single employer for FMLA purposes if the entities pass the “integrated employer” test. If that test is met, all employees of the separate entities must be counted to determine if the company is a covered employer. In applying the test, look at the entire relationship and consider the following questions:

- Is there common management? This may include common directors and boards.

- Is there an interrelation of operations? This could include common work areas, common recordkeeping, and shared bank accounts and equipment.

- Is there centralized control of labor relations? This may involve such responsibilities as hiring and firing, performance evaluations, and promotions.

- Is there a degree of common ownership/financial control?

Joint employers

- An employee’s primary employer is responsible for satisfying FMLA responsibilities in a joint employment relationship.

- The secondary employer should not discriminate or retaliate against an employee on FMLA leave.

Where two or more businesses exercise some control over the work or working conditions of the employee, the businesses may be joint employers under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Joint employers may be separate and distinct entities with separate owners, managers, and facilities.

Where an employee performs work which simultaneously benefits two or more employers, or works for two or more employers at different times during the workweek, a joint employment relationship generally will be considered to exist. This is often the case when dealing with temporary employment agencies.

In a joint relationship, the primary employer is responsible for satisfying the basic FMLA responsibilities to an employee taking FMLA leave, while the secondary employer is prohibited from discriminating or retaliating against that employee.

Successor in interest

- FMLA obligations apply to a business that is a successor in interest to another business.

Under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), a business that is a successor in interest to another business has FMLA obligations, including assuming the FMLA responsibilities of the predecessor employer as well as meeting its own FMLA obligations.

If there is continuity of the same business operations with the same plant, workforce, jobs, working conditions, supervisory personnel, and similar machinery, equipment, products, and services, the predecessor and the successor are considered the same employer for purposes of FMLA coverage.

Policy considerations

- A covered employer’s FMLA policy should include more information than the required FMLA poster.

Once a company becomes a covered employer, it must post the FMLA poster. It might also want to consider crafting a Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) policy. This could include more information than the FMLA poster has. The policy could, for example, point out which method the company uses to calculate the 12-month leave year period, it could also indicate whether the company will allow employees to take FMLA leave on an intermittent or reduced schedule basis when leave is taken for bonding with a healthy child. A policy could also include procedures for employees.

Other forms of leave

An FMLA policy should take into consideration other forms of leave that might need to be coordinated. If a company has, for example, maternity leave, the company will want to ensure that the policy speaks to it, such as whether it is run concurrently with FMLA leave or not. A company might also want the policy to address coordination with any other paid leave, such as vacation, sick leave, or PTO.

Leave entitlement

- Covered employees are entitled to take up to 12 workweeks of FMLA leave.

Before any employee begins leave, employers benefit from knowing how long the employee is entitled to be on leave, what the leave year is, and how to handle paid leave in regard to Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave.

Covered employers must allow eligible employees to take up to 12 weeks of FMLA leave in a 12-month leave year period for certain reasons. In some situations, eligible employees are not automatically entitled to intermittent or reduced schedule leave. Eligible employees are entitled to up to 26 weeks of FMLA leave in a single 12-month period for military caregiver reasons.

The 12 weeks are not necessarily 480 hours. A week of FMLA leave for an employee depends on what the employee's usual workweek is.

The FMLA is an employee entitlement law; a company may not deny FMLA leave simply because an employee’s absence would pose a challenge. The law does not include an undue hardship defense. How the work gets done despite an employee’s absence is generally up to employers to determine.

- Employees may take intermittent FMLA leave for a variety of reasons.

Eligible employees may take Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave on an intermittent (or reduced schedule) basis when medically necessary, to proceed with adoption or foster care placement, or for qualifying family military emergencies.

When leave is needed for a serious health condition, there must be a medical need for it to be taken on an intermittent basis. A company may not require an employee to take more leave than is necessary to address the situation. The certification should indicate that intermittent leave is needed.

Employees may take intermittent leave for planned or unplanned medical treatment, or for recovery from treatment, or to provide care, including psychological comfort to a family member with a serious condition.

Chronic conditions often involve intermittent leave, sometimes foreseeable, and sometimes not. The employee need not receive treatment by a health care provider for each instance of intermittent leave, and employers may not request a certification (or doctor’s note) for each instance of intermittent leave.

Employer-approved intermittent leave

When leave is taken strictly for bonding with a healthy child, whether by birth, adoption, or foster placement, an employee is not automatically entitled to intermittent (or reduced schedule) leave. The employee may take leave on this basis only if the employer agrees.

Airline flight crew employees

- Specific FMLA entitlements apply to eligible airline flight crew members.

Airline flight crew employee: An airline flight crewmember or flight attendant as those terms are defined in regulations of the Federal Aviation Administration.

Eligible airline flight crew employees are entitled to up to 72 days of Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave during any 12-month period for the same reasons that other employees would be entitled to up to 12 weeks of leave. The same qualifying reasons apply:

- The birth of a child or placement of a child for adoption or foster care;

- To care for the employee’s spouse, son, daughter, or parent with a serious health condition;

- For the employee’s own serious health condition; or

- For any qualifying exigency arising out of the fact that a spouse, son, daughter, or parent is a military member on covered active duty.

The 72-day entitlement is based on a uniform six-day workweek for all flight crew employees, regardless of the time actually worked or paid. This is multiplied by 12 weeks. For example, if Amy took five weeks of FMLA leave, she would use 30 days (6 days x 5 weeks) of her 72-day entitlement; her schedule is notwithstanding.

Eligible airline flight crew employees are entitled to up to 156 days of military caregiver leave during a single 12-month period to care for a covered servicemember. This 156-day entitlement is based on the uniform six-day workweek multiplied by the 26-workweek entitlement for military caregiver leave.

Holidays and vacations

- Holidays and vacations may or may not change an employee’s FMLA entitlement.

When determining the amount of leave, when an employee is taking FMLA leave on a continuous basis, a holiday occurring within a week of Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave has no effect. The week is still counted as a week of FMLA leave.

However, if an employee is using FMLA leave in increments of less than one week (intermittent or reduced schedule), the holiday will not count against the employee's FMLA entitlement, unless the employee was otherwise scheduled and expected to work during the holiday.

If a company's activities temporarily cease for one or more weeks and employees generally are not expected to report for work, the employer may not count, as FMLA leave, the days on which the company's activities have ceased.

Leave for birth, adoption, foster placement

- Leave for the birth, adoption, or foster placement of a child must conclude leave within 12 months from the date of the birth, adoption, or placement.

When an employee is out on Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave for the birth of a child, the adoption of a child, or the foster placement of a child, the employee must conclude leave within 12 months from the date of the birth, adoption, or placement. This applies no matter what the 12-month leave year period is. If, for example, an employer uses the calendar year method to calculate the 12-month leave year period, and an employee gives birth on April 12, the employee would need to complete the leave for bonding by the following April 12.

Leave year

- FMLA regulations require a company to specify how it will designate a leave year.

- Employers may choose from four distinct categories of leave year designation.

The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) regulations state that employers must designate which method a company will use to measure the 12-month period in which the 12 weeks of entitlement will fall. Employers may choose from the following:

- The calendar year,

- Any fixed 12-month leave year (for example, August 1 to July 31),

- The 12 months measured forward from the date an employee begins leave, or

- A rolling backward 12-month period.

The military caregiver leave year must run on a measured forward basis, no matter which method is used to calculate the other, 12-month period for the other qualifying reasons.

If a state law requires a company to designate one of the above for the leave year, the company should go with that leave year for all employees — at least in that state. The Department of Labor has indicated, in an unpublished letter, that employers may be unable to choose one method from among the available regulatory options if a state family and medical leave law dictates a particular method.

When this is the case, employers covered by both state and federal laws would follow the state provisions. Some employment attorneys, however, discount this letter.

Calendar year

If employers choose the calendar year, the 12 months begin on January 1 and end on December 31 for all eligible employees. In this situation, an employee may end up with up to 24 consecutive weeks of leave if the leave begins 12 weeks before the end of the year. In this situation, the employee may be eligible for another 12 weeks of leave beginning the new year, which brings the consecutive total up to 24 weeks.

Fixed 12-month

This can be any fixed period that encompasses 12 months. Some companies prefer to use the fiscal year to designate as the FMLA leave year. In this situation, all employees have the same leave year, similar to the calendar-year method.

Another example of a fixed 12-month period is one that begins on an employee's anniversary date. With this situation, employees would have different leave years.

Since employees are not eligible for FMLA leave unless they have worked for the company for at least 12 months (even though these months need not be sequential), using the anniversary date can make it easy to determine when an employee may begin to take leave.

12 months measured forward

With this method of calculating a leave year, not only will there be different leave years for each employee, but there would be different leave years based upon when an employee's leave began. This method of measuring a leave year begins when an eligible employee first takes leave. So, once an employee begins leave, the leave year is established for that year. The employee's next 12-month period would begin the first time FMLA leave is taken after completion of any previous 12-month period.

This method may help reduce the chance of employees stacking leave as employees might with a fixed 12-month or calendar year. If leave is taken on a reduced schedule or intermittent basis, the employee would still be eligible for 12 workweeks in a 12-month period.

Rolling backward

With this method, there is no set 12-month period. When an employee requests FMLA leave, employers look back 12 months from the date any leave is taken. If the employee has not taken any leave in those previous 12 months, the employee has 12 weeks available on that date. If, however, the employee has taken leave within the last 12 months from any date the employee takes leave, employers must first figure out if the employee has any leave available. If any leave was taken prior to the previous 12 months, the employee's 12 weeks of leave is reduced by the amount of leave taken — at least as of that particular day.

Another way of looking at this method is like that of a snapshot of the 12-month period that changes daily: as each new day is added to the 12-month period, one day from 12-months ago is eliminated. The year continues to roll.

Early returns

- Employees have the right to return to their original job when returning from FMLA, even if returning earlier than expected.

If, while an employee is out on Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave, circumstances change and the employee no longer has a need for FMLA leave, the employee’s FMLA leave is concluded, and the employee has an absolute right under the law to be promptly restored to the employee’s original position or an equivalent position of employment.

Employers may not require the employee to take more leave than is necessary to respond to the need for FMLA leave, and may not impose the entire requested leave upon the employee if it is not needed.

That doesn’t mean, however, that if an employee shows up at work unannounced before the expected return date, the employee may simply return to the job. A company may require that the employee give it reasonable advance notice, generally at least two working days, before returning to the employee’s position. This highlights the importance of communication during an FMLA-related situation.

Paid leave

- A company may require an employee to use accrued paid leave for otherwise unpaid FMLA-qualifying leave.

The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) generally provides for unpaid leave.

If a company provides paid leave such as vacation, sick leave, or other accrued paid time off, which could run concurrently with FMLA leave, the employee may elect or a company may require the employee to take such leave concurrently with otherwise unpaid FMLA leave. Any remaining FMLA leave in the 12-month period beyond the paid leave may be unpaid.

Company leave policy

An employee’s ability to substitute accrued paid leave for otherwise unpaid FMLA leave is determined by the terms and conditions of normal leave policies.

A company may also require that such paid leaves be substituted for (used concurrently with) otherwise unpaid FMLA leave, as long as the reason for the leave is FMLA-qualifying.

- A company is generally under FMLA deadlines as soon as an employee alerts it of the need for leave.

The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) process generally begins when an employee alerts the employer of the need for leave. Once this is done, the FMLA clock begins ticking, and the Wage and Hour Division (WHD) and courts are enforcing the deadlines. Employees are, however, required to provide appropriate notice information in a timely manner.

Employees are required to put the employer on notice of the need for leave, and this should include enough information to give the company an idea that the leave could be for an FMLA-qualifying reason.

Employees do not, however, need to assert their FMLA rights, or even mention the FMLA when putting an employer on notice of the need for leave. An employee’s unusual behavior has been seen as providing adequate notice.

Two employee notice scenarios generally exist — when the employee’s leave is foreseeable and when it is unforeseeable.

Foreseeable need for leave

- Employees must provide a company with advanced notice of their foreseeable FMLA leave needs.

- If 30 days' advance notice is not possible, an employee must notify the employer of the need for leave “as soon as practicable.”

Employees seeking to use Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave are required to provide at least 30 days advance notice before FMLA leave is to begin when the need is foreseeable and such notice is feasible.

This could be for situations such as an expected birth of a child, placement for adoption or foster care, a planned medical treatment for a serious health condition, or planned medical treatment for a serious injury or illness of a covered servicemember.

Whether the leave is to be continuous, taken intermittently, or on a reduced schedule basis, an employee has to give the employer initial notice only one time for a given reason. If, however, things like dates change, the employee needs to let the company know.

As soon as practicable

Furthermore, when leave is foreseeable and an employee is not able to provide 30 days’ notice, then the employee is to give notice “as soon as practicable.” This would mean at least verbal notification to the employer within one or two business days of when the need for leave becomes known to the employee.

Sometimes the employee will not provide the employer with 30 days advance notice of foreseeable leaves. In those situations, if employers ask, the employee must explain why providing notice in a timely manner was not practicable.

“As soon as practicable” means as soon as both possible and practical, and this will depend upon the facts and circumstances of the individual situation. The employee should be able to provide notice either the same day of learning of the future need for leave or the next business day.

For foreseeable leave, the employee should give at least a verbal notice with enough information to make the employer aware that the employee needs FMLA. The information should also include the following:

- The expected timing and duration of the leave;

- Whether the condition renders the employee unable to perform the functions of the job;

- That the employee is pregnant or has been hospitalized overnight;

- Whether the employee or family member is under the continuing care of a health care provider;

- If the leave is for a qualifying exigency;

- If the leave is for a family member, whether the condition is pregnancy or otherwise renders the family member unable to perform daily activities; or

- That the family member is a covered servicemember with a serious injury or illness.

If the employee is requesting leave for the first time for an FMLA-qualifying event, the employee does not need to mention the FMLA or otherwise assert FMLA rights. If the employee is requesting leave for an FMLA-qualifying reason and has taken leave for the reason before, the employee must specifically reference the qualifying reason or the need for FMLA leave.

If the employee does not provide adequate information, the company should inquire further about whether the employee is seeking FMLA leave and obtain enough details to indicate that FMLA is involved.

Calling in sick without providing more information will not be considered sufficient notice to trigger the employer’s FMLA obligations.

Employees must respond to questions designed to determine whether an absence potentially qualifies for FMLA. Failure to do so may result in the denial of FMLA protection if the employer can’t determine whether the leave actually does qualify for FMLA.

Employees planning to have medical treatment must consult with the employer to schedule the treatment so the absence does not unduly disrupt the company's operations. Of course, the schedule would need to be OK with the health care provider. The schedule should suit the needs of the company and the employee.

Unforeseeable need for leave

- An employee or the employee’s spokesperson may give the company notice of the need for FMLA leave in unforeseeable situations such as an emergency.

If an employee has a situation that is unforeseeable and is unable to notify the employer 30 days before the employee needs to take leave, notice must be given as soon as practicable. Circumstances under which unforeseeable situations could occur include the following:

- A change in circumstances,

- A lack of knowledge of approximately when leave will be required to begin, or

- An emergency, such as a car accident.

It should generally be practicable to provide notice of the need for leave within the time prescribed by the employer’s usual and customary leave notice policies or requirements.

If an employee is unable to give notice, a spokesperson (i.e., spouse, adult family member, etc.) may. Even if the employer has a requirement of advance written notice, it can’t be applied to prevent an employee from taking FMLA leave in an emergency.

Company policy

- It is lawful for an employer to require notice of FMLA leave except in the case of unusual circumstances, such as an emergency.

Employers may require employees to comply with their usual and customary notice and procedural requirements for requesting Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave unless there are unusual circumstances.

This could include requiring employees to provide written notice that indicates the reasons for the requested leave as well as the anticipated start and duration of the leave. Employers may also require employees, per policy, to contact a specific individual.

For unforeseeable leave, if an employee requires emergency care, the employee would not be required to follow the call-in procedure until the condition improved. Such a situation would also preclude written advance notice of the need for leave.

If there are no unusual circumstances and the employee does not comply with the notice requirements, FMLA-protected leave may be delayed or denied.

Employee failure to provide notice

- An employer may deny or delay FMLA leave if an employee fails to provide proper notice.

If an employee fails to give 30 days’ notice for foreseeable leave, and has no reasonable excuse for the delay, an employer may delay Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave 30 days from the date the employee requests leave.

FMLA leave may be delayed because an employee failed to give proper notice only if it was clear the employee knew about the FMLA notice requirements and the leave was clearly foreseeable. The obligation is met if the employer has properly posted the FMLA notice at work.

If an employee fails to provide timely notice of unforeseeable leave, and no extenuating circumstances justify the delay, the employer may deny or delay the FMLA leave, but much will depend upon the specific facts involved.

If, for example, it would have been practicable to provide notice very soon after the need for leave arose, but the employee provided notice two days after the leave began, the employer could delay FMLA coverage by two days.

Responding to a leave request (including employee eligibility)

- The FMLA regulates how and when employers must respond to an employee’s request for leave.

Once an employee has put a company on notice of the need for leave, Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) obligations are initiated and the FMLA clocks generally begin ticking. Notices need to be provided to the employee, questions may need to be asked, answers sought. Failure to respond appropriately or timely could risk a claim.

Employers are to provide employees an eligibility/rights and responsibilities notice within five days of being put on notice of the need for leave. The employer is to complete the notice before giving it to the employee.

Once an employer has enough information — such as from a certification — that the employee’s reason for leave qualifies for FMLA protections, the employer has five days to give the employee a designation notice.

Employee eligibility

- An employee’s eligibility to take FMLA leave is determined by three criteria.

When an employer learns of an employee’s need for Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave, it must ensure that the employee is eligible to take leave.

There are three basic eligibility criteria that an employee of a covered employee must meet:

- The first is that an employee must have been employed by a company for at least 12 months. Employers should be able to determine this easily by looking at the employee’s hire date(s). The 12 months need not be consecutive.

- The second criterion is that the employee must also have worked at least 1,250 hours for the employer during the 12-months before leave is to begin.

- The third eligibility criterion is that the employee must work at a worksite where there are at least 50 company employees within 75 miles of the worksite.

Please note that flight crewmembers have alternative eligibility criteria.

12 months

- Some exceptions apply to the FMLA criteria that an employee must have worked for the company for 12 months, though the months need not be consecutive.

The 12 months that an employee must have worked for the company to be eligible to take Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave need not be consecutive. Employment periods prior to a break in employment of seven years or more, however, need not be counted in determining whether the employee has been employed for the company for at least 12 months.

There are exceptions. Employment periods preceding a break of more than seven years must be counted where:

- The employee's break in employment was to fulfill National Guard or Reserve military obligations. The time served performing the military service must also be counted in determining whether the employee has been employed for at least 12 months for the company. However, employees don't have any greater entitlement than under the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act (USERRA).

- A written agreement including a collective bargaining agreement exists concerning the employer’s intention to rehire the employee after the break in service (for example, for the purpose of an employee furthering education or for childrearing).

Occasionally, an employee will need leave before meeting the 12-month eligibility criterion. In that situation, the employer would count only leave taken after the employee meets that criterion as FMLA leave. Any leave taken before the employee meets the criterion, however, would not be counted as FMLA leave.

1,250 hours

- As part of determining if an employee is eligible to take FMLA leave, an employer must determine if the employee has hours enough worked.

- An employer should count regular and overtime hours toward an employee’s qualifying FMLA leave criteria of 1,250 hours worked.

When an employee notifies a company of the need for Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave, the employer must determine if the employee has worked enough hours to be eligible for leave. Employees must have worked at least 1,250 hours in the 12 months before leave is to begin.

Hours worked: A concept taken from the FLSA and governed under 29 CFR 785. Hours worked generally includes only hours actually worked and in which the employee performs service for the employer, but also include waiting time, on duty, off duty, on-call, and time used for rest.

When it comes to counting the 1,250 hours worked, all hours worked, regular and overtime, are to be included. With a few exceptions, hours not actually worked are not to be counted. Such time off as vacation, annual or sick leave, paid or unpaid holidays, or Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave is not counted.

If employers have employees who are sometimes on call, the hours of service generally include only all “duty” time. The FMLA again turns to the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). On-call time is not counted unless the use of the time is so restricted the employee is not able to use the time for the employee’s own purposes. An employee who is required to remain on call while at home, or who is allowed to leave a message where the employee can be reached, or who carries a pager for call response is not working (in most cases) while on call. Additional constraints on the employee’s freedom could require this time to be compensated.

All periods of absence from work due to or necessitated by leave under the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act (USERRA) are to be counted in determining an employee’s eligibility for FMLA leave. This means that, for example, if an employee was on military leave for six months, the time spent during those six months would be counted toward the employee’s eligibility criteria of working for the company for 12 months and 1,250 hours in the preceding 12 months before leave began.

The employer needs to look at the hours the employee worked. This would include hours worked from home or another location away from the general worksite if the employer has constructive knowledge of the employee's hours worked.

For those employees for whom employers do not keep records of hours worked, such as those who are considered exempt under the FLSA, if the employee has worked for the employer for at least 12 months, these employees are presumed to have worked the minimum number of hours, unless the employer proves differently.

When looking at the hours-of-service requirement, look at the previous 12 months as 52 weeks.

When figuring out if an employee has met the 1,250 hours of service and 12-month requirements, an employer must make this determination as of the date the leave begins. Generally, eligibility does not carry over from one leave year to the next.

50 employees, 75 miles

- The last of the three employee eligibility criteria is that of working at a site with at least 50 company employees within 75 miles of the worksite.

The last of the criteria for employee eligibility for Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave requires that employees work at a site with at least 50 company employees within 75 miles of the worksite. If employers have only one worksite, this test will be easy: If there are at least 50 employees, employees will meet this eligibility test. If a company has multiple locations, temporary help offices, and satellite offices, this can be more of a challenge.

The employee count at a location depends on the number of employees who are on the payroll as of the date an employee requests leave. This is different than the 12-month/1,250-hour determination, which needs to be made as of the date leave begins.

Part-time and full-time employees, and employees on paid or unpaid leaves of absence are all included for the 50/75 count. Employers do not have to count employees who have been laid off, whether or not the layoff is temporary, indefinite, or long-term.

If an employee requests leave at a time when an employer has fewer than 50 employees within 75 miles, the employee may resubmit the request if the employee count rises to 50 or more. On the other hand, if an employee requests leave at a time when an employer has 50 or more employees, the employer may not rescind the granting of the employee’s leave just because the employee total has fallen below 50 by the time the leave begins.

Employers should measure the 75-mile distance by surface miles using available transportation by the most direct route between worksites. This is not always on the basis of a radius.

An employee’s private residence is not considered a worksite. Rather, the employee’s worksite is the location from which assignments come and to where the employee generally reports. An employee who works from her home in Cincinnati but reports to an office in Chicago would have Chicago as her worksite.

Temporary employees

- The time employees worked for both the company and the temp agency should be counted toward FMLA eligibility.

If employers have temporary employees, the time such employees work for both the employer and the temp agency are to be counted toward Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) eligibility. A temporary help agency and an employer are considered joint employers for purposes of determining employee eligibility (and employer coverage) under the FMLA. Consequently, the time an employee was employed by a temporary help agency would be counted toward the eligibility test.

The worksite for employees of a temporary employment agency is the site from which the work is assigned — that is, the employment agency. Therefore, all temporary employees assigned by the temporary employment agency, regardless of whether the customers’ worksites are within 75 miles of the agency’s office, are included in the employee count for the temporary employment agency office in determining if staff employees are eligible for FMLA leave.

Flight crew members

- Flight crewmembers have different FMLA leave eligibility criteria.

Employers with employees who are flight crewmembers will need to use different eligibility criteria. These employees need to meet the following guidelines:

- Worked or been paid for at least 60 percent of the employee’s applicable monthly guarantee, and

- Worked or been paid for at least 504 hours (not counting personal commute time or time spent on vacation leave or medical or sick leave) during the previous 12-month period.

For employees who are not on reserve status, the “applicable monthly guarantee” is the minimum number of hours for which the employer has agreed to schedule the employee for any given month.

For employees who are on reserve status, the “applicable monthly guarantee” is the minimum number of hours for which the employer has agreed to pay the employee for any given month. This may be established in an applicable collective bargaining agreement or in the employer’s policies.

Eligibility notice

- A company has five business days to provide an employee needing FMLA leave with an eligibility notice.

- Eligibility is based on three criteria.

Once the employer learns of the need for Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave, it has five business days to provide the employee with an eligibility notice. Eligibility shouldn't take too much work to determine; the company needs to ensure the employee has worked for at least 12 months (need not be continuous) for the company, has worked at least 1,250 hours in the last 12 months, and works at a site with at least 50 company employees within 75 miles. If the employee needing leave meets these criteria, the employee will be eligible to take FMLA leave for a qualifying reason. If the employee doesn’t meet these criteria, the employer will need to indicate this in the eligibility notice.

Employers need to provide an eligibility notice for leave taken for each FMLA-qualifying reason. All FMLA absences for the same qualifying reason are considered a single leave, and employee eligibility for that reason does not change during the applicable 12-month period.

Notification of eligibility may be verbal or in writing, and the employer may use the Department of Labor’s (DOL) model eligibility notice to meet this requirement.

Rights and responsibilities notice

- Employers must provide employees with a rights and responsibilities notice in addition to the FMLA eligibility notice.

In addition to the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) eligibility notice, employers must provide written notice about the specific employee expectations and obligations along with any consequences for not meeting those obligations. This information is to be provided when the eligibility notice is provided, which logically explains why the Department of Labor (DOL) combined the two notices into one document.

The rights and responsibilities notice must include the following (not a complete list):

- That leave might be designated as FMLA and counted against the employee's entitlement;

- Certification requirements;

- Which method is used to calculate the 12-month leave year period;

- Provisions for substituting accrued paid leave;

- The right to health care coverage maintenance;

- Health care plan premium payment requirements and provisions, and consequences for failure to make payments;

- Liability for employer-paid plan premiums reimbursement, if applicable;

- “Key” employee status; and

- Other information such as status report requirements.

Along with this rights and responsibilities notice, the employer may provide a certification form for the employee to have completed when the reason for leave is not to bond with a healthy child.

Additional documents

Employers may provide more than the eligibility and rights and responsibilities notice. Additional documents could include a letter or memo to the employee, a copy of the company policy regarding Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave, a leave request form, a certification form (if applicable), and perhaps a copy of the FMLA poster. These are not, however, required.

Reasons for leave

- Employees may request FMLA leave for several reasons.

Covered employers are required to provide eligible employees job-protected, unpaid FMLA leave for qualifying reasons. Not every reason an employee needs time off from work will qualify for FMLA protections. There are basically six reasons that qualify for leave under the FMLA:

- Birth of a child (12 weeks),

- Placement with an employee of a child for adoption or foster care (12 weeks),

- An employee’s serious health condition (12 weeks),

- The serious health condition of an employee’s family member (12 weeks),

- To handle any qualifying exigency caused by a family member’s covered active military duty (12 weeks), or

- To care for a family member with a serious injury or illness obtained or aggravated in the line of active military duty (26 weeks).

Key definitions

- Several key definitions are used to describe reasons for FMLA leave.

Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) reasons for leave include the following definitions:

Covered active duty: For family members in the regular Armed Forces, this is duty during the deployment of the member to a foreign country. For family members in a reserve component of the Armed Forces, this is duty during the deployment of the member to a foreign country under a federal call or order to active duty in support of a contingency operation.

Covered servicemember: For current members, this includes members of the regular Armed Forces as well as National Guard or Reserves who are undergoing medical treatment, recuperation, or therapy, or are otherwise in outpatient status or on the temporary disability list for a serious injury or illness. For veterans, this includes those who are undergoing medical treatment, recuperation, or therapy for a serious injury or illness at any time during the period five years before the date on which the veteran undergoes such treatment, recuperation, or therapy.

In loco parentis: Refers to a relationship in which a person is put in the situation of a parent by assuming and discharging the obligations of a parent to a child. The in loco parentis relationship exists when an individual intends to take on the role of a parent to a child who is under 18 or 18 years of age or older and incapable of self-care because of a mental or physical disability. Although no legal or biological relationship is necessary, grandparents or other relatives, such as siblings, may stand in loco parentis to a child under the FMLA as long as the relative satisfies the in loco parentis requirements.

Incapacity: The inability to work, attend school, or perform other regular daily activities. This inability must result from the condition, treatment for the condition, or any treatment in connection with the condition, including any subsequent treatment or incapacity relating to the initial condition.

Inpatient care: At least an overnight stay in a medical facility such as a hospital, hospice, or residential medical care facility.

Outpatient status: The status of a member of the Armed Forces assigned to either a military medical treatment facility as an outpatient, or a unit established for the purpose of providing command and control of members of the Armed Forces receiving medical care as outpatients.

Birth of a child

- Eligible employees may take up to 12 weeks of FMLA leave for the birth of a child.

The first qualifying event for Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave is the birth of a child. This does not include just the time the child is born and immediately thereafter. An expectant employee (birth mother or spouse) may schedule leave to include prenatal care.

FMLA leave to care for a pregnant woman is available to a spouse and not, for example, to a boyfriend or fiancé, even if the person is the father of the child. This is because there is no legal familial relationship between the mother and the father unless the couple are married.

Leave taken for the birth of a child is not limited only to the child’s birth mother. Any employee who just became a new parent would be entitled to leave. If, however, both married parents work for the company, it could require the parents to share the leave. That means that the couple is collectively eligible for 12 weeks of leave, not for 12 weeks of leave each to bond with a healthy baby. This limitation, however, does not apply to unmarried couples working for the same employer.

In the case of multiple births, the 12-week entitlement does not apply to each child (i.e., an employee is not entitled to 24 weeks of FMLA leave if she delivers twins).

Employees need not have a biological or legal relationship to a new baby to take FMLA leave for bonding. If the employee plans on standing in loco parentis to the baby — plans to take on day-to-day responsibilities to care for or financially support the baby — the employee will be considered a parent, and be able to take FMLA leave to bond with the baby. This will apply regardless of the gender of the parents.

There is no limit on the number of “parents” a child may have. As long as an individual has assumed the obligations of a parent, the person may be seen as standing in loco parentis.

Leave taken for the birth of a child must be completed within 12 months of the birth.

An employer is not required to allow an employee to take leave on an intermittent or reduced schedule basis when the leave is taken solely for bonding with a healthy child.

Adoption or foster care placement

- Employees adopting a child or receiving placement of a child through foster care may qualify for 12 weeks of FMLA leave.

Eligible employees may take Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave for the adoption of a child or the placement of a child through foster care. Leave entitlements for such events apply to both parents. Leave for the adoption or placement of a child must be completed within 12 months of the adoption or placement.

When an employee adopts a child or receives foster placement of a child, leave may also include time prior to the actual placement for placement-related business.

For purposes of the FMLA, it does not matter if the adoption is through a licensed placement agency or not. If an employee receives a child for foster care, however, there must be state action involved.

In loco parentis

As long as the employee intends to assume parental responsibilities, the employee may be seen as intending to stand in loco parentis to a child.

Serious health condition

- FMLA leave may be taken by eligible employees for a qualifying serious health condition or to care for a family member with a serious health condition.

Eligible employees may take Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave for a serious health condition or to care for a family member with a serious health condition.

A serious health condition is an illness, injury, impairment, or physical or mental condition that basically involves treatment connected with:

- Inpatient care (i.e., an overnight stay) in a hospital, hospice, or residential medical care facility; or

- Continuing treatment, which can involve one or more of the following:

- A period of incapacity requiring absence of more than three, consecutive, full calendar days from work, school, or other regular daily activities that also involves:

- Treatment of at least twice by (or under the supervision of) a health care provider, or

- Treatment at least once followed by a regimen of continuing treatment (e.g., a prescription, therapy requiring special equipment; or

- Any period of incapacity due to pregnancy or for prenatal care; or

- Any period of incapacity (or for such treatment) due to a chronic serious health condition (e.g., asthma, diabetes, epilepsy, etc.) or treatment for it; or

- A period of incapacity that is permanent or long-term due to a condition for which treatment may not be effective (e.g., Alzheimer’s, stroke, terminal disease, etc.); or

- Any absence to receive multiple treatments (including any period of recovery that follows) by, or on referral by, a health care provider for a condition that likely would result in incapacity of more than three consecutive days if left untreated (e.g., chemotherapy, physical therapy, dialysis, etc.).

The term “serious health condition” is intended to cover conditions or illnesses that make an employee (or a family member) unable to perform the essential functions of the employee’s or family member’s job, go to school, or otherwise live a normal life. This means that the condition affects a person’s health to the extent that inpatient care is required, or absences from work for more than a few days are necessary for treatment or recovery. It is not intended to cover short-term conditions for which treatment, and from which recovery, is very brief, since such conditions normally are covered by the company’s sick leave policies.

It does not matter if the condition is “elective” or not. If, for example, an eligible employee elects to donate a kidney, this would most likely result in the employee needing an overnight stay in a health care facility, and as such, would involve a serious health condition qualifying for FMLA protection. The elective procedure need not be altruistic. If an employee had breast augmenting which resulted in a serious health condition, it would still be a qualifying reason.

Continuing treatment

- Eligible employees may take FMLA leave for reasons related to continuing treatment.

Continuing treatment is where employers will find most of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave situations fall. Generally speaking, eligible employees may take FMLA leave for situations involving continuing treatment if it includes the following:

- Incapacity and treatment,

- Pregnancy or prenatal care,

- Chronic health conditions,

- Permanent or long-term conditions, or

- Absence to receive multiple treatments.

Incapacity and treatment

- FMLA leave may be taken by eligible employees for incapacity and treatment related to a health condition.

The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) definition for incapacity and treatment includes a period of incapacity of more than three full, consecutive, calendar days and subsequent medical treatment for conditions that otherwise qualify as serious. It involves either:

- Two visits to a health care provider (or to a provider of health care services upon referral by a health care provider) within 30 days of onset of the incapacity, or

- One visit followed by a regimen of continuing treatment under supervision of the health care provider seen.

The first, or only, in-person treatment must take place within seven days of the incapacity.

One of the bright-line tests for a serious health condition is one resulting in a period of incapacity of more than three consecutive full calendar days.

A regimen of continuing treatment includes such things as prescription drugs or therapy requiring special equipment. It does not include, by itself, activities that are initiated by the individual without the prescription of a health care provider, such as the use of over-the-counter medications, bedrest, the drinking of fluids, exercises, and other similar measures. Such things, if prescribed by a health care provider, however, can qualify as a regimen of continuing treatment.

Employers do not have to consider routine physicals, eye examinations, and dental examinations as treatment, but should consider examinations that are performed to diagnose or to evaluate whether a serious health condition exists and evaluations of the condition.

Pregnancy

- Employers should treat pregnancy as a serious health condition.

Eligible employees may take Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave when needed for pregnancy. Some pregnancies, however, require more medical attention than others. Pregnancy is similar to a chronic condition in that the patient is periodically visiting a health care provider for prenatal care i.e., “supervision.” A pregnant employee may, however, also experience severe morning sickness or other pregnancy-related conditions. These situations qualify for FMLA leave.

Treat pregnancy as a serious health condition, entitling an eligible employee to leave, including any period of incapacity because of the pregnancy or for prenatal care.

Employees are generally entitled to leave to care for their pregnant spouse for prenatal care or if the pregnant spouse is otherwise incapacitated. This is not true, however, if the partner is not married to the birth mother. There is no legal or familial relationship to the pregnant woman unless the couple are married.

Parents, including fathers, are entitled to leave for the birth of a child because there is a familial relationship between the parent and the child.

In addition to birth parents, those who intend to stand in loco parentis to a child are entitled to leave for the birth. In this situation, there need not be a biological or legal relationship to the child.

Eventually, the employee will need time off for delivery and recovery.

Chronic conditions

- FMLA leave may be taken by eligible employees for qualifying chronic health conditions.

Ailments that continue over an extended period of time (i.e., from several months to several years), often without affecting an individual’s day-to-day ability to work, go to school, or to engage in other life activities, but that cause episodic periods of incapacity of fewer than three days, can qualify as serious health conditions.

Chronic conditions often render the individual incapacitated. To be considered serious health conditions, they must require at least two visits per year to a health care provider for treatment, and the two visits should occur before leave is needed. Employers may, however, allow employees to attend the second visit in the future. Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave may be taken for any absences needed for an incapacity due to chronic conditions — there is no need to have more than three days of incapacity.

Neither the FMLA nor its underlying regulations require employees to comply with medical advice. Employees with conditions such as asthma may also take FMLA leave to avoid incapacitation.

Permanent or long-term conditions

- FMLA leave may be taken by eligible employees for qualifying permanent or long-term health conditions.

A period of incapacity that is permanent or long-term due to a condition for which treatment may not be effective would be considered a serious health condition.

The employee or family member must be under the continuing supervision of, but need not be receiving active treatment by, a health care provider. The condition may not be curable, but may involve a period of incapacity that is permanent or long-term. Treatment, however, may not be effective.

Multiple treatments

- FMLA leave may be taken by eligible employees for qualifying health conditions requiring multiple treatments.

Some conditions require the patient to receive more than one treatment for the condition. These could be such treatments as physical therapy for severe arthritis, restorative surgery after an accident or perhaps cancer, or dialysis for kidney disease. This list is not complete, it just provides some examples. Without these treatments, the employee would be rendered incapacitated for at least three days.

The employee may also need time to recover from such treatments, and this time off is also allowed under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA).

Substance abuse

- Treatment for substance abuse may qualify for FMLA leave for eligible employees.

Substance abuse may be a serious health condition if the other elements of the definition are met. However, an absence because of an employee’s illegal or otherwise violative use of the substance, rather than for treatment, is not protected. An employer may take disciplinary action against an employee pursuant to a uniformly applied substance abuse policy, provided the action is not being taken because the employee has exercised the right to take Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave.

Care for a family member

- FMLA leave may be taken by eligible employees to care for a spouse, parent, or child with a serious health condition.

An otherwise eligible employee may take Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave if necessary to care for a spouse, parent, or child with a serious health condition.

Spouse

When it comes to marriages, spouse is defined under state law for purposes of marriage, including common-law or same-sex marriages. Same-sex marriages are recognized in all U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

Important to note is that this extends only to legal marriages, not to domestic partnerships or civil unions.

Parent

The term “parent” includes biological, adoptive, step, or foster parent, or anyone who stood in as a parent (in loco parentis) to the employee when the employee was a child. This term does not, however, include parents-in-law.

In loco parentis basically means “in the place of a parent.” It is commonly understood to refer to someone who is put in the situation of a lawful parent by assuming the obligations incident to the parental relation without going through the formalities needed for legal adoption. It embodies the two ideas of assuming the parental status and discharging parental duties. An employee would be entitled to FMLA leave, for example, to care for an individual who stood in as a parent to the employee when the employee was a child.

There are factors to be considered in determining in loco parentis status, including, but not limited to, the following:

- The age of the child;

- The degree to which the child is dependent on the person claiming to be standing in loco parentis;

- The amount of support, if any, provided; and

- The extent to which duties commonly associated with parenthood are exercised.

Given this, whether an employee stands in loco parentis to a child will depend on the specific facts involved in a situation.

Child (son or daughter)

A son or a daughter (child) is a biological, adopted, or foster child, a stepchild, a legal ward, or a child of a person standing in loco parentis, who is under 18 years of age or is 18 years of age or older and incapable of self-care because of a mental or physical disability. Again, there does not need to be a biological or legal relationship between the parent and the son or daughter, as mentioned above.

Eligible employees may take FMLA leave to care for an adult child, as long as that child meets all the following criteria:

- Has a disability as defined by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA),

- Is incapable of self-care because of the disability,

- Has a serious health condition, and

- Is in need of care because of the condition.

A disability is generally an impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, such as walking, thinking, eating, bending, hearing, and the normal function of bodily systems such as immune, neurological, circulatory, and endocrine systems. This definition is fairly broad.

An individual is incapable of self-care if the individual needs help with at least three daily living activities such as grooming, personal hygiene, dressing, eating, cooking, cleaning, shopping, paying bills, and maintaining a residence.

Definition of care

- The definition of care for FMLA leave can include physical care, psychological support, taking time to assist the person, and attending school meetings related to a child’s medical needs.

Care for family members can include more than simply tending to their physical needs. It can also include being there for physical and psychological support, such as holding their hand while in the hospital, taking time to get them to medical appointments, and even finding the best health care facilities for them.

While the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) doesn’t generally entitle employees to leave to attend school conferences, if the school meeting involves a child’s related medical needs, it can.

Qualifying exigency

- FMLA leave may be taken by eligible employees for a qualifying exigency.

- Several reasons qualify for exigencies under the FMLA.

The qualifying exigency provisions are intended for those with family members who serve in the Reserves or National Guard and are called to military duty as well as those who are members of the regular Armed Forces.

There are several different reasons that qualify for exigencies under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). These include the following:

- Short-notice deployment — to address issues that arise because a servicemember is notified of an impending call or order to active duty seven or fewer calendar days before the date of deployment. Leave taken for this purpose can be used for a period of seven calendar days beginning on the date the servicemember is notified of an impending call or order to active duty.

- Military events — to attend any official ceremony, program, or event sponsored by the military and to attend family support or assistance programs and informational briefings sponsored or promoted by the military, military service organizations, or the American Red Cross that are related to the active duty or call to active duty.

- Childcare and school activities — to address childcare and school activities that require attention because the servicemember is on active duty or call to active duty status, not routine events that occur regularly for all parents. The employee does not need to be related to the military member’s child. However, the military member must be the employee’s spouse, parent, or child; and the child for whom the employee is taking leave must be the child of the military member. Qualifying exigency leave is not to be taken for childcare on a routine, regular, or everyday basis.

- Financial and legal arrangements — to make or update financial or legal arrangements to address the servicemember's absence, such as preparing and executing financial and health care powers of attorney, transferring bank account signature authority, enrolling in the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System, obtaining military identification cards, or preparing or updating a will or living trust.

- Counseling — to attend counseling provided by someone other than a health care provider. This counseling could be for the employee, the servicemember, or a child of the servicemember, provided the need for counseling is because of the covered active duty.

- Rest and recuperation, leave — to spend time with a servicemember who is on short-term, temporary rest and recuperation (R&R) leave. Leave taken for this reason may last up to 15 days for each instance of rest and recuperation, and is to be used only during the military member's R&R leave.

- Post-deployment activities — to attend arrival ceremonies, reintegration briefings and events, and any other official ceremony or program sponsored by the military for a period of up to 90 days following the end of covered active duty. Leave for this reason may also be taken to address issues that arise from the death of a servicemember, such as meeting and recovering the body and making funeral arrangements.

- Parental care — to address certain activities related to the care of the military member’s parent who is incapable of self-care. These could include arranging for alternative parental care; providing care on a non-routine, urgent, immediate need basis; admitting or transferring the parent to a new care facility; and attending certain meetings at a care facility or with hospice staff. Note: The employee does not need to be related to the military member’s parent. However, the military member must be the employee’s spouse, parent, or child; and the parent for whom the employee is taking leave must be the parent of the military member.

- Other — to address other events that arise because of the servicemember's active duty. The employer and the employee are to agree that such leave qualifies as an exigency and agree to both the timing and duration of the leave.

Qualifying exigencies definitions

- The FMLA provides definitions for son or daughter and covered active duty regarding qualifying exigencies.

Son or daughter

For purposes of qualifying exigencies, a son or daughter includes an employee's biological child, adopted child, foster child, stepchild, legal ward, or a child for whom the employee stood in as a parent (in loco parentis). There are no age restrictions in the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) regulations for children regarding qualifying exigencies, as the military already provides for this.

Covered active duty

For members of a regular component of the Armed Forces, this term is defined as duty during the deployment of the member to a foreign country.

For members of a reserve component of the Armed Forces, this term is defined as duty during the deployment of the member to a foreign country under a call or order to active duty in support of a contingency operation. The definition is said to cover a broad array of assignments. The U.S. code governing the Armed Forces defines it as one that results in the call or order to, or retention on, active duty of members of the uniformed services, or any other provision of law during a war or during a national emergency declared by the President or Congress.

Deployment to a foreign country means deployment to areas outside of the United States, the District of Columbia, or any territory or possession of the United States, including international waters.

Military caregiver

- FMLA leave may be taken by eligible employees to care for a servicemember with a serious injury or illness that was incurred or aggravated in the line of active military duty.

Eligible employees who are the spouse, son, daughter, parent, or next of kin of a covered servicemember may take Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave to care for a servicemember with a serious injury or illness that was incurred or aggravated in the line of active military duty. Employees may also take the leave to care for a family member who is a veteran who receives care within five years of becoming a veteran.

Employees are entitled to take up to 26 workweeks of leave during a 12-month period to care for the servicemember. The leave is available only during a single 12-month period.

An eligible employee may take no more than 26 workweeks of military caregiver leave in any “single 12-month period.” The 26-workweek entitlement is to be applied as a per-servicemember, per-injury entitlement. This means that an eligible employee may take 26 workweeks of leave to care for one covered servicemember in a “single 12-month period” and then take another 26 workweeks of leave in a different “single 12-month period” to care for another covered servicemember or to care for the same covered servicemember with a subsequent serious injury or illness.

An eligible employee is entitled to a combined total of 26 workweeks of military caregiver leave and leave for any other FMLA-qualifying reason in a “single 12-month period,” provided that the employee may not take more than 12 workweeks of leave for any other FMLA-qualifying reason. It is only where the two 12-month periods overlap that an employee is restricted to 26 weeks of leave.

The “single 12-month period” for military caregiver leave begins on the first day the eligible employee takes military caregiver leave and ends 12 months after that date, regardless of the method used by the employer to determine the employee’s 12 workweeks of leave entitlement for other FMLA-qualifying reasons. Therefore, leave taken to care for a servicemember is to be calculated on the “measured forward” basis.

Next of kin

- Next of kin is defined as someone’s nearest blood relative beyond spouse, parent, son, or daughter.

Next of kin is defined as someone’s nearest blood relative other than spouse, parent, son, or daughter. Next of kin is in the following order of priority:

- Blood relatives who had legal custody of the servicemember,

- Brothers or sisters,

- Grandparents,

- Aunts and uncles, and

- First cousins.

The servicemember may designate, in writing, another blood relative as next of kin for caregiver leave purposes. If so, that designated person would be the only next of kin to consider.

When no such designation is made, however, and there are multiple family members with the same level of relationship to the servicemember, all such family members must be allowed to take Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave to provide care.

Covered servicemember

- A covered servicemember is defined as both a current member of the Armed Forces and a veteran of the Armed Forces.

Covered servicemembers are both current members of the Armed Forces and veterans of the Armed Forces. For current members, this includes members of the regular Armed Forces as well as National Guard or Reserves who are undergoing medical treatment, recuperation, or therapy, are otherwise in outpatient status, or are otherwise on the temporary disability list, for a serious injury or illness.

For veterans, this includes those discharged from the regular Armed Forces, the National Guard, or Reserves under conditions other than dishonorable within the five-year period before an employee first takes military caregiver leave to care for that veteran. The veteran would need to be undergoing medical treatment, recuperation, or therapy for a serious injury or illness.

The servicemember must be undergoing medical treatment, recuperation, or therapy; is otherwise in outpatient status; or is otherwise on the temporary disability retired list for a serious injury or illness.

Certification

- Employers should provide employees requesting FMLA leave with the certification form (except if leave is strictly for bonding with a healthy child).

A major part of Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) administration is the certification. It is through this document that the players get involved. Employers give the form to the employee, the employee has the form completed by a third party (often a health care provider), and the company obtains it. The information in the certification should be adequate to help a company determine whether the reason for an employee’s absence qualifies for FMLA protections.

Once requested, employees have at least 15 days to provide employers with a certification. Employers, on the other hand, must adhere to restrictions regarding certifications (and recertifications) including not asking for more information than the Department of Labor indicates on its forms, not asking for such information too often, and keeping medical information confidential.

A company may request an initial certification once an employee has put the company on notice of the need for leave. The same is true for annual certifications when an employee’s need for leave spans multiple leave years.

The certification form may be provided to the employee via the U.S. mail (first class, certified, etc.), in person, or electronically. Whichever method is used, the company might want to have a means of substantiating that the employee received the form (as well as the eligibility/rights and responsibilities notice and the designation notice).

The company may not mandate that a certification be in a particular form or format, if the employee provides the pertinent information.

Certification forms

- Five different certification forms are provided by the DOL for FMLA leave situations.

The Department of Labor (DOL) provides five different certification forms for use in appropriate of Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave situations. The forms are as follows:

- Certification of Health Care Provider for Employee's Serious Health Condition,

- Certification of Health Care Provider for Family Member's Serious Health Condition,

- Certification of Qualifying Exigency for Military Family Leave,

- Certification for Serious Injury or Illness of a Current Servicemember for Military Family Leave, and

- Certification for Serious Injury or Illness of a Veteran for Military Family Leave.

Pregnancy, delivery, and recovery all entail a serious health condition. Therefore, if an employee is pregnant and will be delivering a child, an employer may use the employee serious health condition certification. If the employee is taking time off to care for the person who gave birth, the employer may use the family member serious health condition certification.

For situations in which an employee is off because the employee is bonding with a healthy child or because the employee adopted or will be a foster parent of a healthy child, however, there really is no certification form to use. In fact, an employer may not require an employee to provide a certification for bonding with a healthy child. Employers may, however, require employees to provide reasonable documentation or statement of family relationship. The employer may only review official documents and must return the documents to the employee.

In any case, an employee may satisfy such a requirement to confirm a family relationship by providing either a simple statement asserting that the requisite family relationship exists, or documentation. It is the employee’s choice whether to provide a simple statement or another type of documentation. In all cases a simple statement of family relationship is sufficient to satisfy the request.

Therefore, if an employee tells an employer that the employee’s relationship with an individual meets the criteria for a family member, the employer may not ask for more information. Employers may not demand that an employee provides a particular document as proof. The employer may, however, require that the employee’s statement be put in writing.

Certifications for qualifying exigency cannot come from health care providers, as leave for a qualifying exigency cannot be for medical reasons.

Timing

- Employees who fail to return certification when it was possible to do so within 15 calendar days from receipt may forfeit FMLA protections.

- Employers may have a policy that allows for more than 15 days, if desired.

After receiving the certification and information on requiring one, the employee has at least 15 calendar days from receipt to return it, complete and sufficient. There may be situations in which circumstances prohibit the employee’s good-faith efforts to meet that 15-day requirement. If so, employers will need to allow for such extenuating circumstances. Employers may also have a policy that allows for more than 15 days, if desired.

If the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave is foreseeable, and at least 30 days’ notice has been provided, the employee should return the certification to the employer before leave begins. If this is not possible, the employee then must provide the certification to the employer within the time frame requested (at least 15 calendar days after the request), unless not practical.

Unfortunately, some employees miss this 15-day deadline, and for various reasons. In some situations, employers might need to provide more than 15 days. An employer’s actions will depend upon whether the leave is foreseeable or unforeseeable.

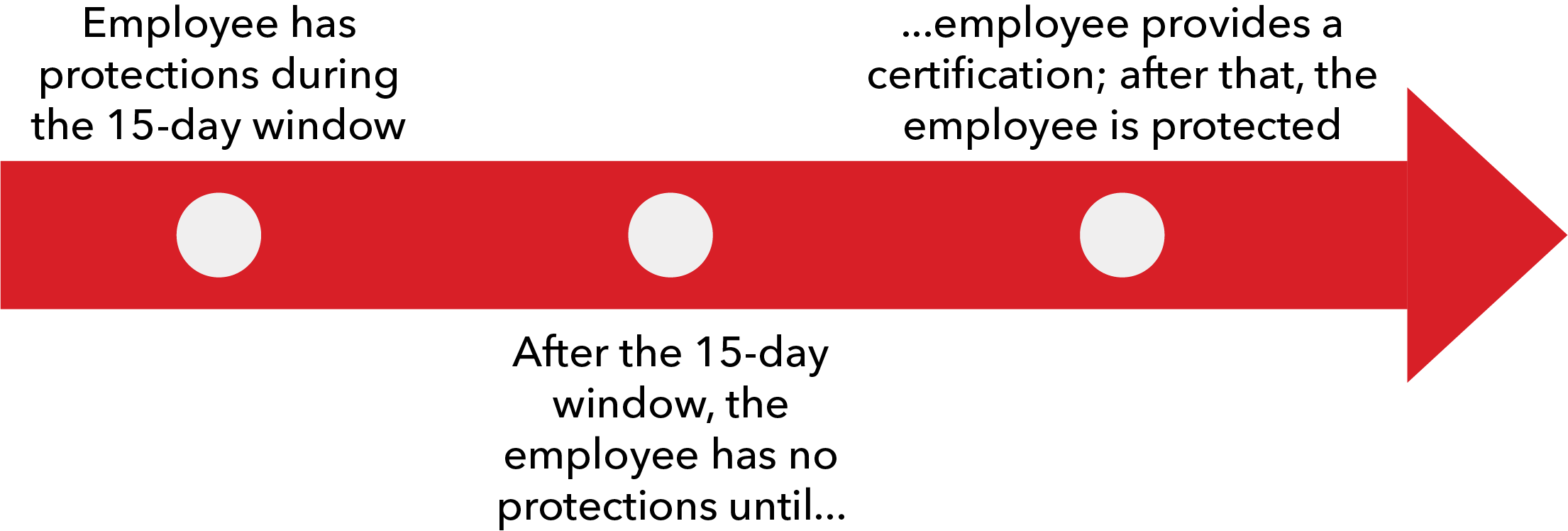

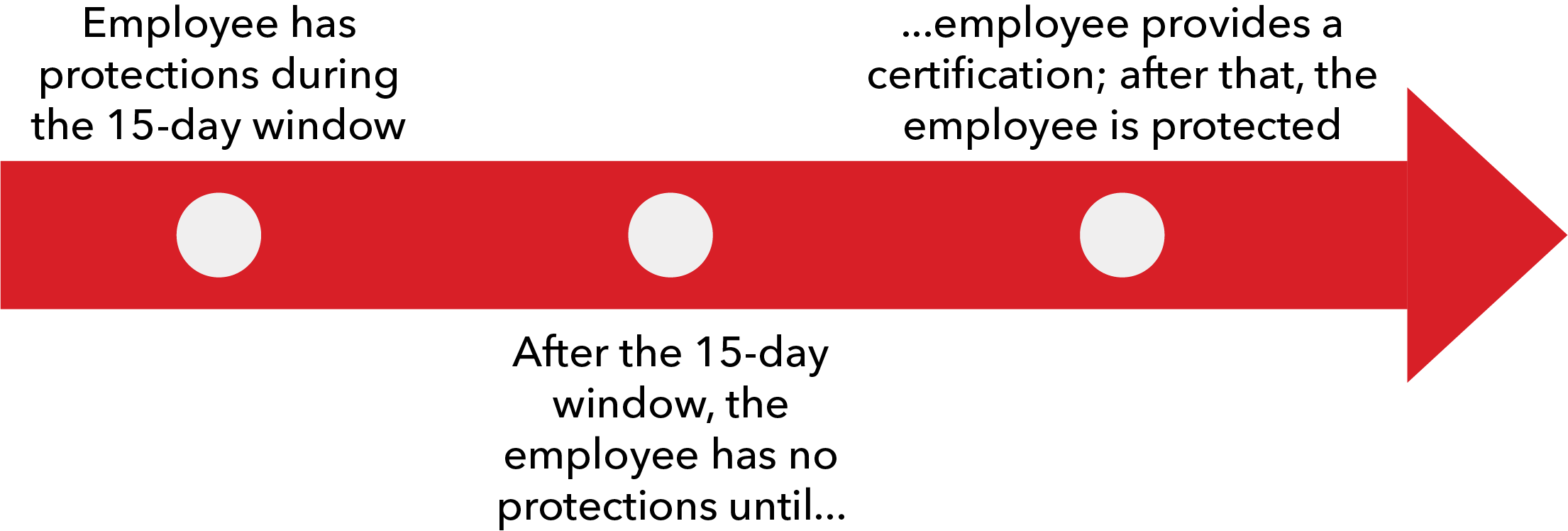

- When the employee’s need for leave was foreseeable and the employee fails to provide a certification within 15 days, the employer may deny FMLA coverage until the required certification is provided. When leave is foreseeable, employees are to provide advance notice of the need for leave, and, therefore, are in a better position to provide the certification earlier. For example, if an employee is requesting leave for an upcoming birth, the employee should provide notice of the need for leave at least 30 days in advance. The employee then should be able to provide a requested certification well before the leave is to begin. If, for example, an employee had 15 days to provide a certification, but doesn’t do so for 21 days without sufficient reason for the delay, the employer may deny FMLA protections for the six days after the 15-day window has closed, as long as the employee takes leave during those 21 days.

- When the employee’s need for leave is unforeseeable, the employer may deny FMLA coverage for the requested leave if the employee fails to provide a certification within 15 days from receipt of the request for the certification, unless not practicable due to extenuating circumstances. For example, if an employee is involved in an automobile accident, it may not be practicable for the employee to provide the required certification within 15 days. If, however, there are no extenuating circumstances, and the employee fails to timely return a certification, the employer may deny FMLA protections for the leave following the expiration of the 15-day time period until a sufficient certification is provided. Extenuating circumstances could include the doctor being away for a period of time and not being able to complete the certification. If an employee is putting forth good faith efforts to get a certification, an employer might want to give the employee the opportunity to do so.

Where there is no justification for the delay, as indicated, the employer need not apply the FMLA’s protections, at least for part of the absence. The employee has FMLA protections during the 15-day window.

Complete and sufficient

- An employee requesting FMLA leave must provide a company with a requested certification that is complete and sufficient.

The employee requesting Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) leave must give the employer a complete and sufficient certification. Complete means that all of the entries are completed. Sufficient means that the information provided is not vague, ambiguous, or nonresponsive.

While a medical certification should include the clearest information that is practicable for the health care provider to include regarding the employee's need for leave, precise responses are not always possible, particularly regarding the frequency and duration of incapacity of chronic conditions. Over time, health care providers should be able to provide more detailed responses based on knowledge of the employee's (or family member's) condition.

Deficient certification