Every business must deal with waste, whether it’s solid waste, used batteries and lamps, or waste that has hazardous constituents. A company needs to know how to dispose of waste in the most efficient, cost effective, safe, and environmentally friendly way.

Most states are authorized to run their own solid and hazardous waste programs, so a company needs to be aware of state (and often local) waste regulations. Hazardous waste laws are enforced at both the federal and state level, and improper or negligent hazardous waste mismanagement can result in civil and/or criminal penalties. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) is the United States’ federal solid and hazardous waste law.

Generally speaking, the more toxic the substance the company is managing (and the more of it the business has), the more it’s going to cost in time, effort, and money to dispose of it properly. But it’s important to manage waste correctly, not only because conservation of resources is the right thing to do, but also because waste mismanagement can have severe legal and monetary consequences. Hazardous waste civil penalties are steep, running into the tens of thousands per violation per day, which can add up very fast.

Remember that hazardous waste is regulated from “cradle to grave,” meaning from the moment it is generated until its ultimate disposal (and sometimes beyond, in the case of mismanaged waste). While there’s a lot to know about proper solid and hazardous waste management and disposal, it all boils down to correctly identifying waste streams and working to minimize the impact on the environment.

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA )

- RCRA gives EPA the authority to control hazardous waste from cradle to grave.

- ORCR’s mission is to protect human health and the environment by ensuring responsible national management of hazardous and nonhazardous waste.

- RCRA is divided into three main programs under Subtitles D, C, and I.

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) is the U.S. federal solid and hazardous waste law. RCRA is often used interchangeably to refer to the law, regulations, and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) policy and guidance on waste management.

RCRA is actually a combination of the first federal solid waste statutes and all subsequent waste amendments. Congress enacted the Solid Waste Disposal Act (SWDA) in 1965 to provide states with incentives to manage waste in a safe and responsible manner. The SWDA was amended in 1976 by RCRA, which laid out the framework for the current hazardous waste management program.

Since then, the Act has been amended several times, including the Hazardous and Solid Waste Amendments of 1984, the Federal Facilities Compliance Act of 1992, and the Land Disposal Program Flexibility Act of 1996. In addition, the Energy Policy Act of 2005 amended Subtitle I of RCRA to strengthen the underground storage tank regulations.

RCRA gives EPA the authority to control hazardous waste from “cradle to grave,” including the generation, transportation, treatment, storage, and disposal of hazardous waste. RCRA also created the framework for the management of non-hazardous solid wastes and enables EPA to address environmental problems that could result from underground tanks storing petroleum and other hazardous substances.

The goals set by RCRA include:

- Protecting human health and the environment from the potential hazards of waste disposal.

- Conserving energy and natural resources.

- Reducing the amount of waste generated.

- Ensuring that wastes are managed in an environmentally sound matter.

EPA’s Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery (ORCR) implements RCRA. ORCR’s mission is to protect human health and the environment by ensuring responsible national management of hazardous and nonhazardous waste.

RCRA is cited under 40 CFR 239 – 282 and is divided into three main programs under Subtitles D, C, and I.

RCRA Subtitle D

Subtitle D of RCRA governs non-hazardous solid waste requirements.

These regulations ban the open dumping of waste and set the minimum federal criteria for municipal waste and industrial waste landfills, including the design, location restrictions, financial assurance, corrective action, and closure requirements.

RCRA Subtitle C

Subtitle C of RCRA focuses on hazardous solid waste management requirements.

These regulations ensure that hazardous waste is managed safely from the moment it is generated to its final disposal (i.e., cradle to grave). Under Subtitle C, EPA sets the criteria for hazardous waste generators, transporters, and treatment, storage, and disposal facilities. This includes permitting requirements, enforcement, and corrective action (or cleanup).

RCRA Subtitle I

Subtitle I of RCRA protects groundwater from leaking underground storage tanks.

These regulations require owners and operators of new tanks and existing tanks to prevent, detect, and clean up releases, and train employees in leak detection and emergency response. It also bans the installation of unprotected steel tanks and piping.

Determining hazardous waste

- EPA calls waste identification the most important step in the regulations for generators of solid waste.

The first step in waste management is determining if a business has hazardous waste. Waste determination is also called waste identification or waste characterization. The important regulatory citations related to waste identification are 40 CFR 260 (Hazardous Waste Management System: General); 40 CFR 261 (Identification and Listing of Hazardous Waste); and 40 CFR 268 (Land Disposal Restrictions).

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) calls waste identification the most important step in the regulations for generators of solid waste. If a company fails to identify a waste as a hazardous waste, the business sends it down a path of waste mismanagement — and any associated enforcement actions.

In summary, the requirements for hazardous waste identification include:

- Make a waste determination on waste streams (e.g., compact fluorescent light bulbs, batteries, used oil, production wastes, wastewater, used oil, spent solvents, etc.).

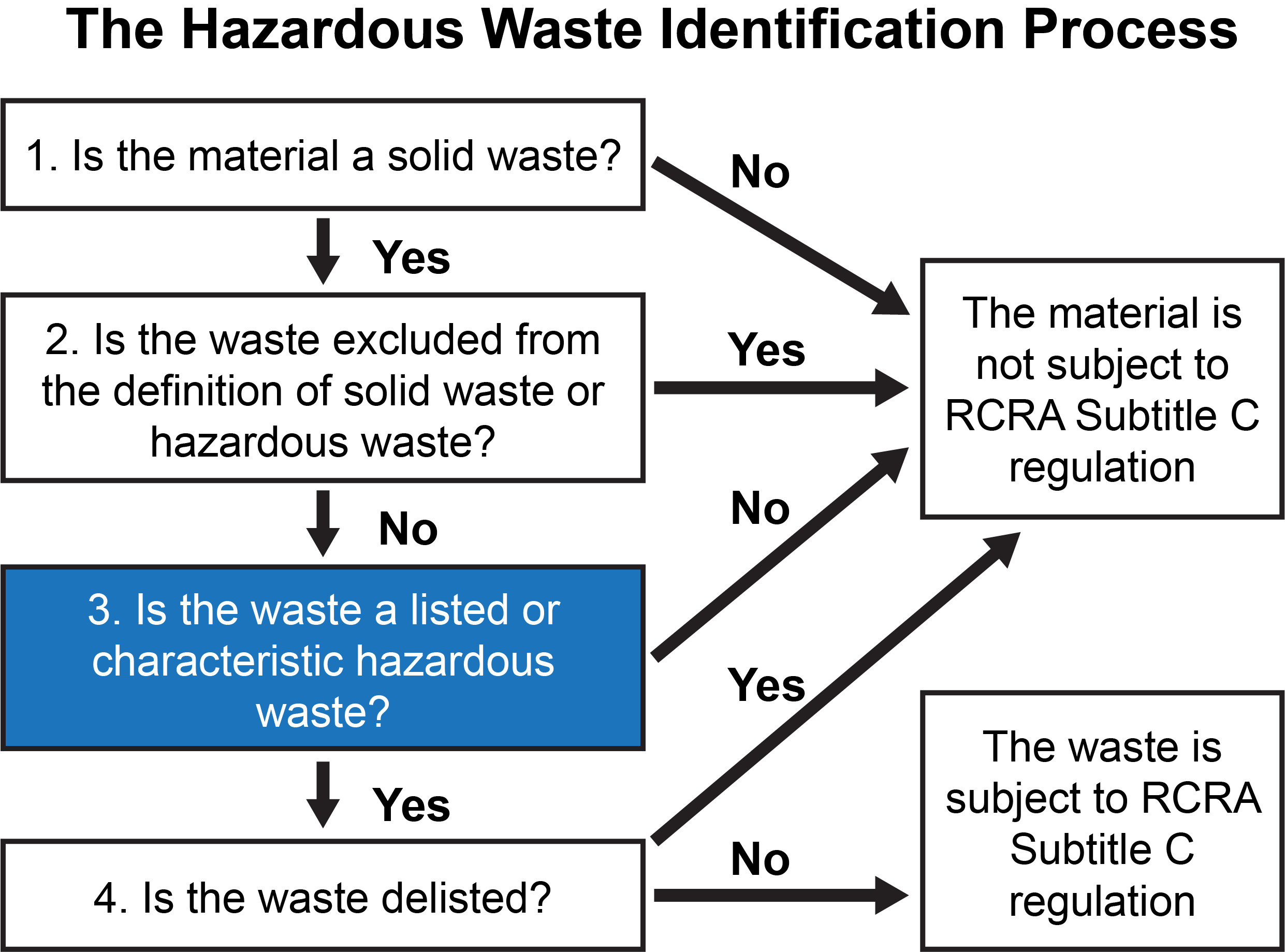

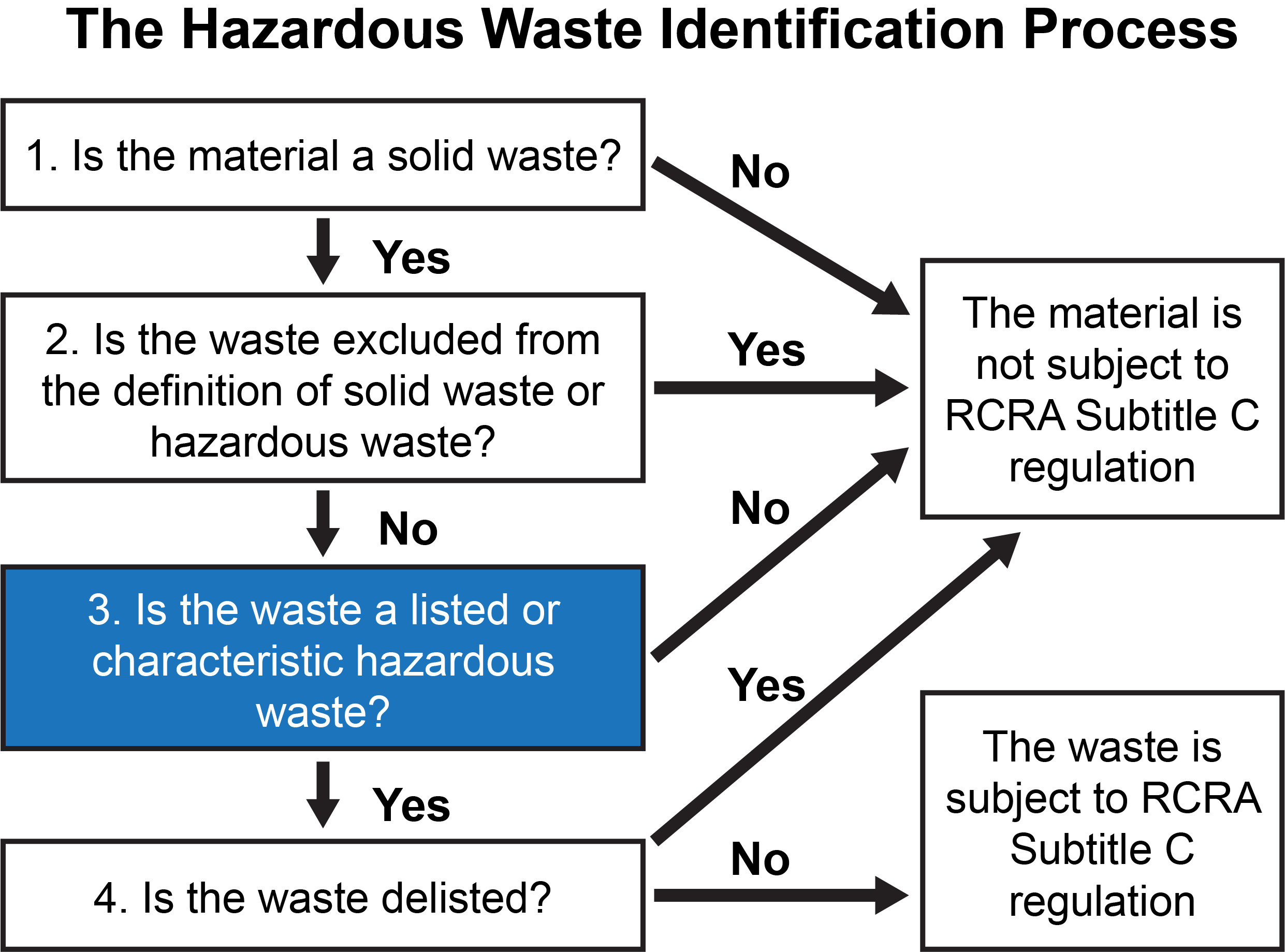

- Go through the steps to determine if the company has a hazardous waste:

- Is it a solid waste?

- Is the waste excluded from the definition of solid waste?

- Is the waste a listed or characteristic hazardous waste?

- Does the waste qualify for an exemption from the definition of solid waste?

- Understand if the waste is prohibited from land disposal and must be treated according to the Land Disposal Restrictions (also known as LDRs).

- Implement a Waste Analysis Plan and keep required documentation.

Identify waste

- Waste must be classified at the point of generation, before any mixing or other alteration of the waste occurs.

- Before making a waste determination for a particular waste, identify all the waste streams at the facility.

When most people talk about a waste, they mean anything that is thrown away. But in regulatory terms, the definition of a waste is very specific. Anything that is still being used, or that is intended to be used or sold, is not a waste. Once a company decides to dispose of it, then it becomes a waste.

Waste must be classified at the point of generation, before any mixing or other alteration of the waste occurs. The “point of generation” is the point at which the material is first identified as a solid waste.

Waste identification is an ongoing obligation. In the case of a waste that may, at some point during its management, exhibit a hazardous waste characteristic, the generator must monitor and reassess the waste.

Before making a waste determination for a particular waste, identify all the waste streams at the facility. This is called a waste survey, and it involves identifying all the wastes — both hazardous and non-hazardous — at the facility.

Once all of the waste streams have been located, the business must identify, or characterize, each waste. To do this:

- Characterize the waste using internal expertise,

- Hire a consultant,

- Use the services of the waste disposal company, or

- Use a combination of all three options above.

To identify a waste, ask the following questions:

- Is it a solid waste?

- Is it an excluded solid waste?

- Is it a hazardous waste?

- Is it exempted from the definition of a hazardous waste?

- Is it a listed waste?

- Is it a characteristic waste?

The flow chart below considers all these questions to help determine whether a waste is subject to Subtitle C of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), which outlines hazardous solid waste management requirements.

Considerations for a waste survey

- EPA requires a company to make a waste determination for all waste streams.

Perform a waste survey by taking a tour of the entire facility (inside and out) to note each and every waste stream. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) requires a company to make a waste determination for all waste streams.

Common waste streams to consider as the waste survey is conducted include:

- Manufacturing processes

- Drains and discontinued lines

- Offices and maintenance areas, electronics, batteries, lamps, thermostats

- Aerosol cans and can puncturing units

- Construction and demolition waste

- Fleet maintenance areas (antifreeze, degreasers, corrosive baths, used oil)

- Laboratories

- Art rooms

- Rags or wipes

- Paints and solvents

- Cleaning activities (power washing areas, housekeeping, and carpet cleaning)

- Yard/Garden care (pesticides, herbicides, degreasers, used oil)

- Maintenance room

Is it a solid waste?

- A solid waste is any material that is abandoned, recycled, considered inherently waste-like, or a military munition.

A solid waste, as defined at 261.2, is any material that is:

- Abandoned

- Recycled

- Considered inherently waste-like

- A military munition

Solid wastes may be disposed of at regular municipal solid waste landfills or combustors, which are considerably less expensive than hazardous waste treatment, storage, or disposal facilities. Note that some states have additional regulations for certain solid wastes that they call “special wastes,” or “industrial wastes,” so be sure to check with the state before sending any solid wastes to the landfill.

In order to be a hazardous waste, a waste must first be a solid waste. While they are called “solid,” solid wastes may be solids, liquids, or even gases.

Excluded solid wastes

If there is definitely a solid waste, check the regulation at 261.4 to see if it is excluded from the definition of a solid waste. The wastes listed below are not considered solid wastes because they are excluded from the definition. These wastes are still regulated, but they are regulated under different environmental programs such as the Clean Water Act (CWA):

- Domestic sewage

- Industrial wastewater discharges

- Radioactive wastes

- Spent wood preserving solutions that are reclaimed and reused in the wood preserving process

- Processed scrap metal

- Secondary materials that are reclaimed and returned to the original process (if the process is totally enclosed)

- Certain other recycled materials

Is it a hazardous waste?

- There is no comprehensive table or list that tell for certain if a solid waste is hazardous.

- Examples of exempted wastes include household hazardous waste, used CRTs, used oil, universal wastes, certain used refrigerants, and lab samples.

If there is a solid waste that wasn’t excluded in 261.4, then a company may have a hazardous waste. There is no comprehensive table or list to tell for certain if the waste is hazardous. For that, continue in the waste identification process.

To be a hazardous waste, the waste must meet the following criteria. The waste is:

- A solid waste (A waste that is not a solid waste cannot be a hazardous waste.); and

- Not specifically exempted from the definition of hazardous waste; and

- A listed hazardous waste; OR

- A characteristic waste.

Exemptions or exclusions from the definition of hazardous waste

If a company determines the waste is hazardous, then refer to parts 124, 264, 265, 266, 268, and 273 for possible exclusions or restrictions to the management of that waste.

Certain hazardous wastes are eligible to be managed under less strict regulatory programs. For example, extensive waste management regulations apply to batteries, but they can be managed as universal wastes at 40 CFR Part 273 rather than as hazardous wastes. The same goes for household hazardous wastes. Homeowners can simply dispose of many wastes in the trash that would be considered hazardous waste if found at a business location (This is not, of course, an environmentally friendly practice, and recycling or disposal at a permitted hazardous waste collection facility is preferable.)

Examples of exempted wastes include:

- Household hazardous waste

- Used cathode ray tubes (CRTs)

- Used oil

- Universal wastes

- Certain used refrigerants

- Lab samples

Listed hazardous waste

- There are over 500 listed hazardous wastes.

- Unused discarded products include those that are spilled by accident as well as products that are intentionally discarded.

- Acute hazardous wastes are so dangerous in small amounts that they are regulated in the same way as large amounts of other hazardous wastes.

Some wastes are hazardous because they are known to pose a threat even when properly managed, regardless of their concentrations. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says it has studied and listed as hazardous hundreds of specific waste streams. In fact, there are over 500 listed hazardous wastes.

There are four hazardous waste lists. They can be found in Part 261 Subpart D. These lists are:

F list (261.31): These are common wastes from nonspecific sources.

The F list is made up of the following groups:

- Spent solvent wastes,

- Electroplating and other metal finishing wastes,

- Dioxin-containing wastes,

- Chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons production wastes,

- Wood preserving wastes,

- Petroleum refinery wastewater treatment sludges, and

- Multi-source leachate.

The F listings refer to “processes only” rather than to specific industries and include wastes from common industrial and manufacturing operations. Because these wastes aren’t industry specific, they are generated by a very large number of facilities.

K list (261.32): These are wastes from specific industries.

Examples include:

- Wood preservation

- Inorganic pigments

- Organic chemicals

- Inorganic chemicals

- Pesticides

- Explosives

- Ink formulation

- Secondary lead

- Coking

- Petroleum refining

- Iron and steel

- Primary aluminum

- Veterinary pharmaceuticals

K wastes are partially defined by the industry in which they are generated and may be unit specific. The industry name for each waste group is listed in the EPA waste number column.

To determine if a waste is a K waste, first determine whether the waste fits within one of the 13 different K list industries.

P list and U list (261.33): These are discarded off-specification, or expired virgin commercial chemical products.

Unused discarded products include those that are spilled by accident as well as products that are intentionally discarded.

Examples include:

- Off-specification commercial chemical products, residue, soil, or debris contaminated by P or U chemicals.

- Container or inner liners removed from a container that held P- or U-listed chemicals. P listings are acutely hazardous wastes. U listings contain toxic constituents. Both the P and the U lists have a narrow applicability to unused commercial chemical products and manufacturing chemical intermediates. Any chemical which has been used for its intended purpose does not meet the P or U listing.

To be a P or a U chemical, the following criteria must be met:

- The waste must be of a commercially pure grade or technical grade of the chemical that is produced and marketed; and

- The chemical must be the sole active ingredient, or the only chemically active component for the function of the product. If a product has more than one active ingredient, it would not qualify as a P or U waste. Inert ingredients, such as fillers, do not prevent a P or U listing. For example, a commercial chemical product containing three percent Kepone as the only active ingredient would be a U listed waste, even though the chemical made up only a small percentage of the product.

Acute hazardous waste

Acute hazardous wastes are a special category of listed hazardous waste. These wastes are so dangerous in small amounts that they are regulated in the same way as large amounts of other hazardous wastes. Many pesticides or dioxin-containing wastes are acutely hazardous wastes.

The important thing to note about these wastes is that if the facility generates as little as 2.2 pounds — approximately one liter — of acutely hazardous wastes in a month, or accumulates that amount over time, the facility must comply with all the regulations that apply to large quantity generators (LQGs) of hazardous waste.

All P codes and all listed hazardous waste codes with an “H” hazard code are acutely hazardous, triggering LQG status at 2.2 pounds.

Hazardous waste numbers and hazard codes

- The hazardous waste number must be marked on the hazardous waste container prior to shipping offsite and must be included on the hazardous waste manifest.

- The hazard codes indicate the basis for the waste being included in the hazardous waste lists.

Industry and EPA Hazardous waste numbers

The F, K, P, and U lists also include the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) hazardous waste number for each waste. This number is important because it must be marked on the hazardous waste container prior to shipping offsite and must be included on the hazardous waste manifest. Sometimes the hazardous waste number is also referred to as the hazardous waste code, but this should not be confused with the hazard code.

There are 149 Industry and EPA hazardous waste numbers on the F and K lists, and 724 on the P and U lists. These are presented in searchable tables available on EPA’s website.

Hazard codes

The hazard codes indicate the basis for the waste being included in the hazardous waste lists. These are:

- Ignitable wastes (I)

- Corrosive wastes (C)

- Reactive wastes (R)

- Toxicity characteristic wastes (E)

- Acute hazardous wastes (H)

- Toxic wastes (T)

Toxic waste (T) is different than toxicity characteristic wastes (E) because the (E) is based on a test called the Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure (TCLP), while (T) is based on the presence of a toxic or hazardous constituent and poses a substantial risk. The description of this test can be found in Appendix II of 40 CFR Part 261.

For further reference, Appendix VII to Part 261 indicates hazardous constituents for which a waste was listed.

Characteristic hazardous waste

- Even if the waste does not appear on one of the four lists of hazardous wastes, it may still exhibit a hazardous characteristic.

- There are four basic hazardous waste characteristics: ignitability, corrosivity, reactivity, and toxicity.

Even if the waste does not appear on one of the four lists of hazardous wastes, it may still exhibit a hazardous characteristic.

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Part 261, Subpart C describes four basic hazardous waste characteristics.

- Ignitability (I): Ignitable wastes can create fires under certain conditions and have a flash point of <140°F. Any waste material that, after testing, exhibits the characteristic of ignitability, but is not a listed waste, is assigned the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) hazardous waste number D001.

- Corrosivity (C): Corrosive wastes are acids or bases that are capable of corroding metal containers, such as storage tanks, drums, and barrels and have a pH of ≤2 or ≥12.5. Any waste material that, after testing, exhibits the characteristic of corrosivity, but is not a listed waste, is assigned the EPA hazardous waste number D002.

- Reactivity (R): Reactive wastes are unstable under “normal” conditions, and can cause explosions, toxic fumes, gases, or vapors when heated, compressed, or mixed with water. Any waste material that, after testing, exhibits the characteristic of reactivity, but is not a listed waste, is assigned the EPA hazardous waste number D003.

- Toxicity (E): Toxic wastes are harmful or fatal when ingested or absorbed, such as poisons. When toxic wastes are land disposed, contaminated liquid may leach from the waste and pollute ground water. Any waste material that, after testing, exhibits the characteristic of toxicity, but is not a listed waste, is assigned an EPA hazardous waste number from D004 to D043. The number will correspond to the identified toxic contaminant. The numbers and contaminants are found in 40 CFR 261.24.

All waste must be considered hazardous until proven otherwise, and generators are responsible for determining if a waste is hazardous because of a hazardous characteristic.

Determination through acceptable knowledge or waste testing

- Generators are responsible for determining if a waste is hazardous because of a hazardous characteristic.

- If a facility cannot use acceptable knowledge to make a waste determination, the regulations require that the facility obtain a representative sample and test the waste.

Generators are responsible for determining if a waste is hazardous because of a hazardous characteristic, and this is done by testing or by applying acceptable knowledge in light of the materials or the processes used to generate the waste.

“Acceptable knowledge” may include:

- Process knowledge (e.g., information about chemical feedstocks and other inputs to the production process);

- Knowledge of products, by-products, and intermediates produced by the manufacturing process;

- Chemical or physical characterization of the wastes;

- Information on the chemical and physical properties of the chemicals used or produced by the process or otherwise contained in the waste;

- Testing that illustrates the properties of the waste; or

- Other reliable and relevant information about the properties of the waste or its constituents.

When a facility uses acceptable knowledge, the facility will manage the waste as hazardous without having to analyze or test it. A facility must document how the determination was made.

Other forms of process knowledge can include:

- Existing published or documented waste analysis data or studies conducted on wastes generated by processes similar to that which generated the waste. Waste analysis data obtained from other facilities in the same industry.

- Facility’s records of previously performed analyses.

- Safety Data Sheets.

Waste testing, sampling, and analysis

If a facility cannot use acceptable knowledge to make a waste determination, the regulations require that the facility obtain a representative sample and test the waste.

Some of the more common tests include:

- Flash point: This tests for ignitability. Examples of materials where this test would apply include paints and solvents.

- pH: This tests for corrosivity and may be used on acids and bases.

- Reactivity: Test as required for Department of Transportation (DOT) classification of hazardous materials. Examples include lithium hydride and trichlorosilane.

- TCLP (Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure): This test is used to determine if a waste will discharge or “leach” contaminants into a sanitary landfill. The specific testing method is outlined in test Method 1311, described in Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Publication SW-846, incorporated by reference in 260.11. A solid waste exhibits the characteristic of toxicity if the contaminant reaches the regulatory level listed in Table 1 at 261.24. For example, if there is a solution with 5 mg/L of lead (D008), that solution exhibits the characteristic of toxicity.

- Total halogens: This test is used for testing used oils for contamination of chlorine, fluorine, bromine, etc., to determine if the used oil may be managed under the less stringent regulations at Part 279 or must be managed as a hazardous waste.

Recordkeeping and generator-controlled exclusion

- Generators must keep records of all waste determinations.

- The generator-controlled exclusion excludes certain hazardous wastes from the definition of solid waste if they are generated and legitimately recycled while under the control of the generator.

Generators must keep records of all waste determinations, including records that identify whether a solid waste is a hazardous waste.

Records must include knowledge of the waste and support the determination. The records must include the following types of information:

- The results of any tests, sampling, waste analyses, or other determinations;

- Records documenting the tests, sampling, and analytical methods used to demonstrate the validity and relevance of such tests;

- Records consulted to determine the process by which the waste was generated, the composition of the waste, and the properties of the waste; and

- Records which explain the knowledge basis for the determination.

Best practices for creating and maintaining a waste characterization record

For each waste, note or include:

- Waste type along with a description

- Source of the waste

- Test results and dates

- Waste analyses records

- Safety Data Sheets

- Sampling procedure

- Representative sample information

- Optional waste characterization form (available from most state waste regulating agencies)

- Disposal facility waste profile

Generator-controlled exclusion

The generator-controlled exclusion at 261.4(a)(23) excludes certain hazardous wastes from the definition of solid waste if they are generated and legitimately recycled while under the control of the generator. To qualify for the exclusions, generators must:

- Notify the authorized state or Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of their recycling activities.

- Ensure adequate containment for their hazardous secondary materials. The rule includes a new definition of contained, which specifies storage units must be in good condition, properly labeled, do not hold incompatible materials, and address potential risks of fires or explosions.

- Comply with emergency preparedness requirements, which will be tailored according to the amount of hazardous secondary materials that are accumulated onsite.

- Keep good records. Generators must maintain records of shipments and confirmations of receipt for transfers of recyclable materials offsite.

Nonhazardous secondary materials (NHSM)

- The NHSM program provides the standards and procedures for identifying whether NHSMs are solid waste under the RCRA when used as fuels or ingredients in combustion units.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) nonhazardous secondary materials (NHSM) program under 40 CFR Part 241 provides the standards and procedures for identifying whether NHSMs are solid waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) when used as fuels or ingredients in combustion units.

Combustion units that burn non-hazardous secondary materials that are not solid waste under RCRA would be subject to 112 Clean Air Act (CAA) requirements for commercial, industrial, or institutional boilers or cement kilns.

Combustion units that burn non-hazardous secondary materials that are solid waste under RCRA would be subject to 129 CAA requirements for solid waste incinerators.

The following NHSM are not solid wastes when used as a fuel in a combustion unit:

- Scrap tires that are not discarded are managed under the oversight of established tire collection programs.

- Resinated wood.

- Coal refuse that has been recovered from legacy piles and processed in the same manner as currently-generated coal refuse.

On March 9, 2016, EPA added three materials to the NHSM list of categorical non-waste fuels. These are:

- Construction and demolition wood processed from construction and demolition debris according to best management practices;

- Paper recycling residuals generated from the recycling of recovered paper, paperboard, and corrugated containers, and combusted by paper recycling mills whose boilers are designed to burn solid fuel; and

- Creosote-treated railroad ties that are processed and then combusted in the following types of units:

- Units designed to burn both biomass and fuel oil as part of normal operations and not solely as part of start-up or shut down operations; and

- Units at major source pulp and paper mills or power producers subject to 40 CFR 63 Subpart DDDDD that had been designed to burn biomass and fuel oil, but are modified (e.g., oil delivery mechanisms are removed) in order to use natural gas, instead of fuel oil.

EPA’s DSW rule

- To be legitimately recycled, the material must meet three factors.

- Under the DSW rule, generators and recycling facilities must meet emergency response and preparedness requirements.

Many of the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) exclusions provide an incentive to recycle certain materials. EPA’s January 2015 final rule amending the 2008 Definition of Solid Waste (DSW) rule clarified the processes and activities that qualify as legitimate recycling activities. These include:

- Exclusions such as the scrap metal exclusion, which allow generators to sell or recycle certain potentially hazardous materials for legitimate uses.

- In-process recycling and recycling of commodity-grade recycled products. In-process recycling involves returning hazardous secondary materials to their original production process.

- Recycling under the control of the generator, including onsite recycling, both within the same company and through tolling agreements.

- Targeted remanufacturing for some higher-value spent solvents that are converted into commercial-grade products.

In May 2018, as ordered by the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, EPA issued a final rule revising its 2015 DSW rule. The 2015 rule required facilities that received recyclable waste to apply for a variance from their state or federal EPA in order to operate.

In its new final rule, EPA will use the 2008 transfer-based exclusion for recyclers. This exclusion calls for receiving facilities to notify EPA of their recycling activities and does not require a variance.

EPA also reconsidered the four factors it had listed in the 2015 rule that qualified an activity as legitimate recycling. The agency kept the first three factors but now says the fourth factor should be considered but is not obligatory.

To be legitimately recycled, the material must meet the following three factors listed in the regulations at 40 CFR 260.43:

- The material must provide a useful contribution to the recycling process or to a product.

- The recycling process must produce a valuable product or intermediate.

- The generator and the recycler must manage the material as a valuable commodity.

The fourth factor, which must be considered in making a determination on the overall integrity of a recycling activity, is that the product of the recycling process does not:

- Contain significant concentrations of any hazardous constituents, or

- Have a hazardous characteristic that similar products do not have.

EPA says that when deciding if a material is legitimately recycled, a facility must evaluate all the factors and consider legitimacy as a whole. If, after careful evaluation of these considerations, the factor in this paragraph is not met, then this fact may be an indication that the material is not legitimately recycled. However, the factor in this paragraph does not have to be met for the recycling to be considered legitimate. In evaluating the extent to which this factor is met and in determining whether a process that does not meet this factor is still legitimate, persons can consider exposure from toxics in the product, the bioavailability of the toxics in the product and other relevant considerations.

Under the DSW rule, both generators and recycling facilities must meet emergency response and preparedness requirements. These requirements are similar to those already in place for large quantity hazardous waste generators; namely, they must make arrangements with local emergency response officials (i.e., local fire departments and hospitals) with facility-specific information to enable a targeted response to a hazardous materials emergency and reduce risk to the surrounding community.

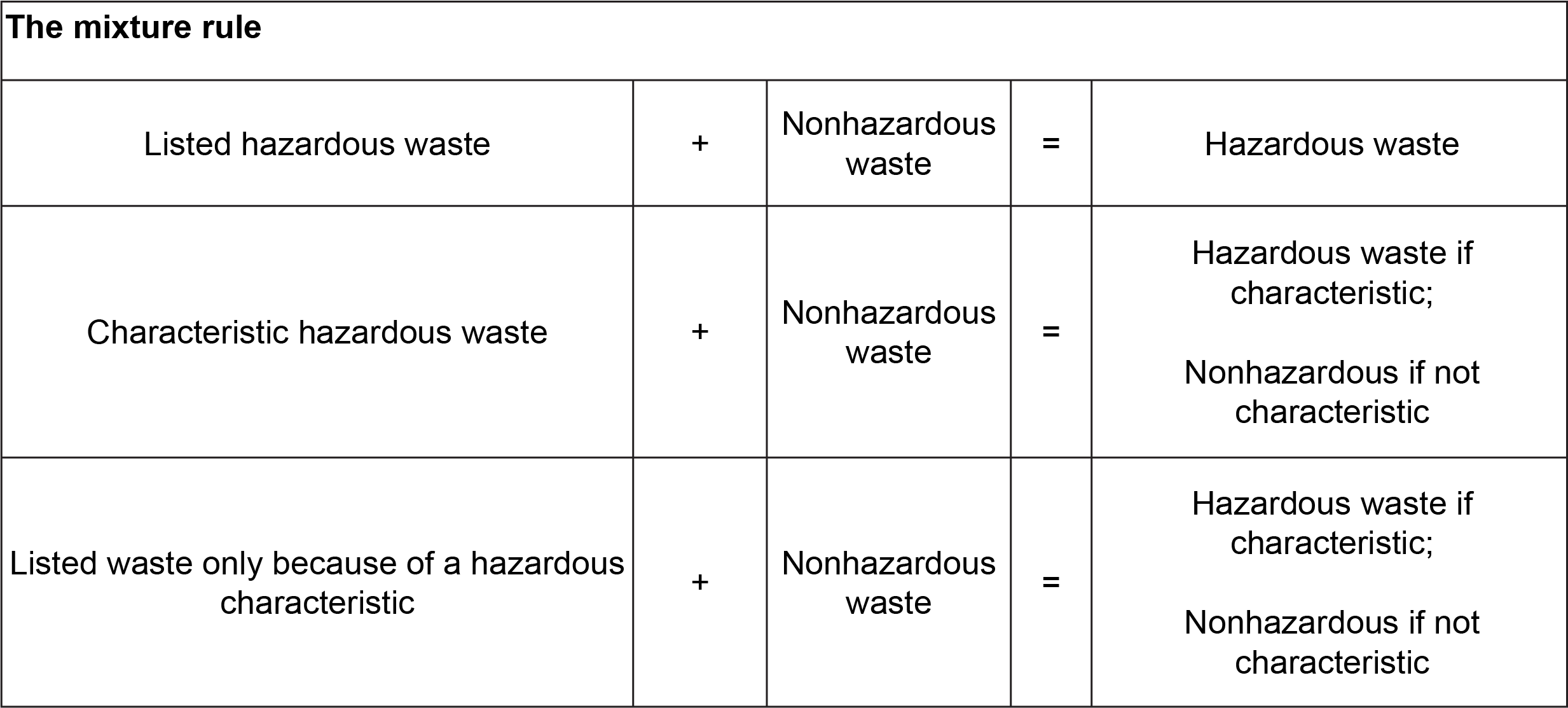

The mixture rule and the Derived-From Rule

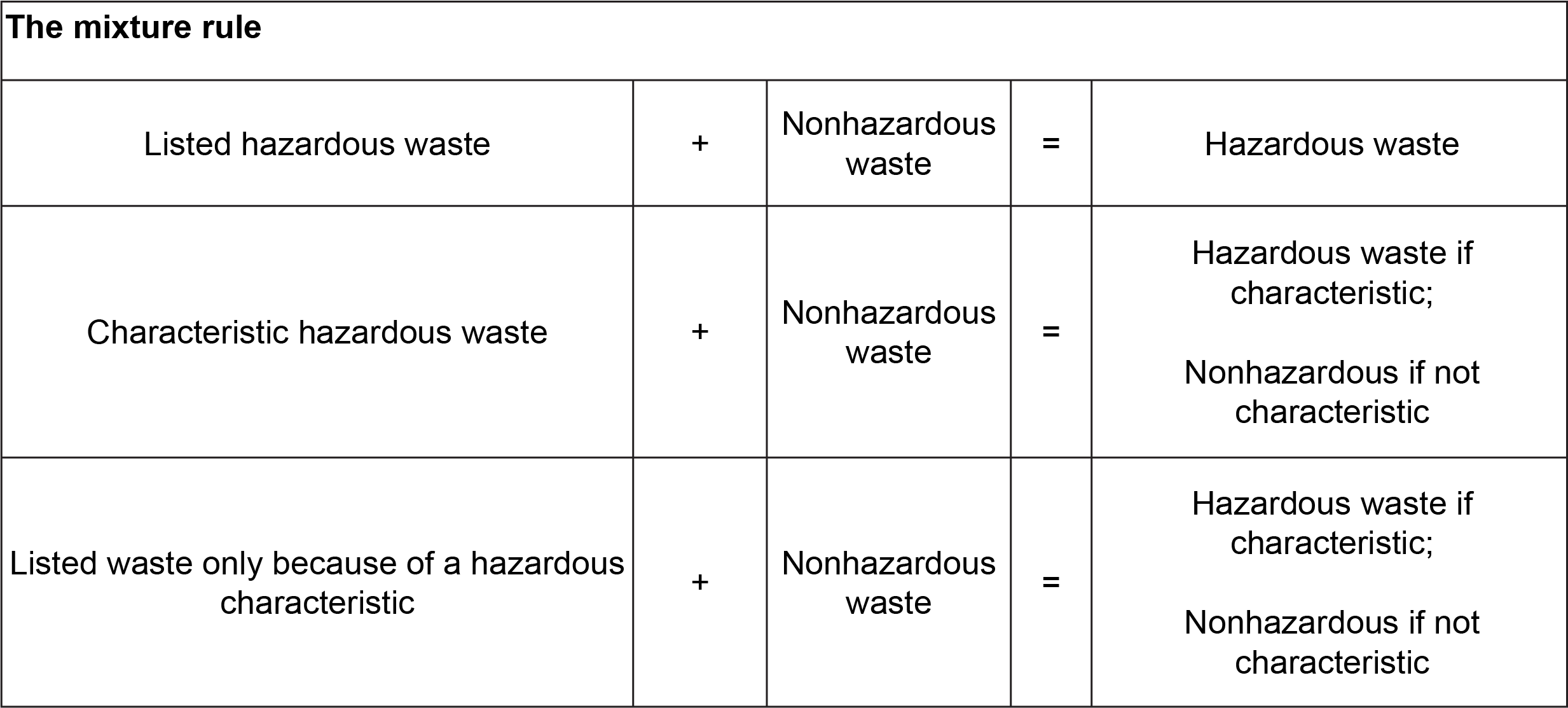

- The mixture rule says that if a facility has a listed waste mixed with a nonhazardous waste, then the entire solution will be a hazardous waste.

- VSQGs of hazardous waste are not subject to the mixture rule.

It is generally a good idea to avoid mixing wastes; however, the mixture rule at 261.3(a)(2) applies if the facility mixes hazardous and nonhazardous wastes. The mixture rule says that if a facility has a listed waste mixed with a nonhazardous waste, then the entire solution will be a hazardous waste. This is why a facility should be very careful with mixing wastes — a facility could end up with much more hazardous waste than intended! For example, if someone pours a halogenated solvent into a full drum of used oil, the entire drum of used oil will now be a hazardous waste.

However, if a facility mixes a characteristic hazardous waste with a nonhazardous waste and the facility ends up with a mixture that does not exhibit a hazardous characteristic, then the mixture can be considered a nonhazardous waste. For example, if someone mixes an acid waste with a basic waste to neutralize it, if the resulting mixture does not test positive for corrosivity (or any other hazardous waste characteristic), then the mixture would not be a hazardous waste. Note that even if a facility treats a waste, it may still be subject to land disposal restrictions in 40 CFR 268.

Finally, the mixture rule says that if a facility has a listed waste that was only listed because it exhibits a hazardous waste characteristic and the facility mixes it with a nonhazardous waste, if the resulting mixture tests as nonhazardous, then the waste is not hazardous.

The table below summarizes the basics of the mixture rule:

Note that very small quantity generators (VSQGs) of hazardous waste are not subject to the mixture rule. They are allowed to mix solid and hazardous wastes together (even if the mixture exceeds the VSQG’s monthly quantity limits), as long as the resulting mixture does not exhibit a hazardous characteristic.

The Derived-From Rule at 261.3(c) covers materials — or residues — that result from treating a listed hazardous waste or a characteristic hazardous waste that continues to exhibit a characteristic. This rule is also known as the “Listed In, Listed Out” rule: Once a facility has a listed waste, the facility always has a listed waste. So even if the facility treats it, the waste will have been “derived from” a listed waste.

However, if the facility treats a characteristic waste, the facility must test the resulting material to see if it still exhibits a characteristic of hazardous waste.

Land Disposal Restrictions (LDRs)

- LDRs require that waste is treated to reduce the hazardous constituents to levels set by EPA, or that waste is treated using specific technology.

- A WAP is required for generator onsite treatment that describes the procedures used to comply with the LDR treatment standards.

The Land Disposal Restrictions (LDRs) require that waste is treated to reduce the hazardous constituents to levels set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), or that the waste is treated using specific technology.

Basically, both small and large quantity generators must determine if their hazardous waste is prohibited from land disposal under the LDRs. A prohibited waste is a waste that does not meet its applicable LDR treatment standards at its point of generation and cannot be land disposed until it meets those standards. If the generator has a prohibited waste, then they must either treat it onsite to meet the standards or send it to an offsite treater or recycler along with the required paperwork. A waste analysis plan (WAP) is required for generator onsite treatment that describes the procedures used to comply with the LDR treatment standards.

The LDR standards are quite complex and have additional requirements for generators, including WAPs, notifications, and certifications.

Notifications

Notifications must include the following information:

- EPA Hazardous Waste Numbers and Manifest number of first shipment.

- A statement saying, “The waste is subject to the LDRs.”

- The constituents of concern for F001-F005, and F039, and underlying hazardous constituents in characteristic wastes, unless the waste will be treated and monitored for all constituents. If all constituents will be treated and monitored, there is no need to put them all on the LDR notice.

- The notice must include the applicable wastewater/non-wastewater category (see 268.2(d) and (f)) and subdivisions made within a waste code based on waste-specific criteria.

- Waste analysis data (when available).

Send a one-time certification to the treatment, storage, and disposal facility (TSDF) with the initial shipment of waste. This certification must say: “I certify under penalty of law that I personally have examined and am familiar with the waste through analysis and testing or through knowledge of the waste to support this certification that the waste complies with the treatment standards specified in 40 CFR part 268 subpart D. I believe that the information I submitted is true, accurate, and complete. I am aware that there are significant penalties for submitting a false certification, including the possibility of a fine and imprisonment.”

If the waste changes, send a new notice and certification to the TSDF and place a copy in their files.

Waste analysis plans (WAPs)

- The facility description is an important element of an effective waste management program (including a WAP).

- Include procedures for receiving wastes generated offsite.

A waste analysis plan (WAP) is required for all treatment, storage, and disposal facilities (TSDFs), as well as generators treating hazardous waste in tanks, containers, or containment buildings to meet Land Disposal Restriction (LDR) standards. Formal documentation of waste analysis procedures in a WAP offers every facility, whether a generator or TSDF, many advantages, including:

- Allowing for planning and analyzing several waste analysis options before making a selection;

- Establishing a reliable and consistent internal management mechanism for properly identifying wastes onsite;

- Ensuring that all participants in waste analysis have identical information (e.g., a hands-on operating manual), thereby promoting consistency and decreasing the likelihood that errors will be made;

- Ensuring that facility personnel changes or absences do not lead to lost information; and

- Reducing liabilities by decreasing the instances of improper handling or management of wastes.

Developing the plan

The facility description is an important element of an effective waste management program (including a WAP). The facility description should provide sufficient, yet succinct, information so that implementing officials and WAP users can clearly understand the type of:

- Processes and activities that generate or are used to manage the wastes,

- Hazardous wastes generated or managed, and

- Hazardous waste management units.

If the facility has an existing Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) permit or is in the process of developing a permit application, the majority of facility description information will be available from other sections of the permit. However, it is useful to include a summary of this information in the WAP. At a minimum, the WAP should reference where in the permit (or permit application) facility description information may be obtained.

Special procedural requirements

Also include procedures for receiving wastes generated offsite; procedures for ignitable, reactive, and incompatible wastes; and provisions for complying with LDR requirements, if applicable.

Description of facility processes and activities

- The WAP should provide a description of all onsite facility processes and activities that are used to generate or manage hazardous wastes.

As a hands-on tool for ensuring compliance with applicable regulatory requirements and/or permit conditions, the waste analysis plan (WAP) should provide a description of all onsite facility processes and activities that are used to generate or manage hazardous wastes (or reference applicable sections of the permit or permit application). This information should include:

- Facility diagrams,

- Narrative process descriptions, and

- Other data relevant to the waste management processes subject to waste analysis.

Since many treatment, storage, and disposal facilities (TSDFs), especially offsite facilities, utilize the WAP as an operating manual, it is advisable to incorporate process descriptions directly into the document.

In addition to describing onsite processes and activities, offsite TSDFs should reference in their WAPs that a brief description of each generator’s processes contributing wastes to the facility will be obtained, updated, and kept on file as part of the operating record (which is reviewed by Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)/state inspectors). If a business owns or operates a TSDF, this data will enhance knowledge of offsite generation processes and, therefore, improve the ability to determine the accuracy of generator waste classification.

Clearly identify the following in a WAP:

- Each hazardous waste generated or managed at the facility,

- Each process generating these wastes,

- Rationale for identifying each waste as hazardous, and

- Appropriate EPA waste classifications (e.g., EPA waste code, classification under Land Disposal Restriction (LDR) regulations as wastewater or non-wastewater).

In addition to identifying all listed wastes generated or managed, a facility may need to conduct testing and/or analysis to determine whether the facility also generates or manages any Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) characteristic wastes. If wastes are identified as characteristic, the facility may choose to present relevant information such as the identity of hazardous waste, process generating the waste, rationale for hazardous waste designation, EPA waste code, and land disposal restriction.

Hazardous waste management units

- The facility description portion of the WAP should include a description of each hazardous waste management unit at the facility.

- In the WAP, the description of the hazardous waste management units at the facility should be provided in narrative and schematic form.

The facility description portion of the waste analysis plan (WAP) should include a description of each hazardous waste management unit at the facility. As a supplement to generic facility process and activity discussions, these descriptions should provide more detailed information regarding the specific operating conditions and process constraints for each hazardous waste management unit.

A hazardous waste management unit is defined in the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) regulations as a contiguous area of land on or in which there is significant likelihood of mixing hazardous waste constituents in the same area. Examples given in the regulations include:

- Container storage areas [Note: A container alone does not constitute a unit; the unit includes containers and the land or pad upon which they are placed.]

- Tanks and associated piping and underlaying containment systems

- Surface impoundments

- Landfills

- Waste piles

- Containment buildings

- Land treatment units

- Incinerators

- Boilers and industrial furnaces

- Miscellaneous units

In the WAP, the description of the hazardous waste management units at the facility should be provided in narrative and schematic form. The narrative description should include the following:

- A physical description of each management unit, including dimensions, construction materials, and components;

- A description of each waste type managed in each unit;

- The methods for how each hazardous waste will be handled or managed in the unit; Process/design considerations necessary to ensure that waste management units are operating in a safe manner and are meeting applicable permit-established performance standards; and

- Prohibitions that apply to the facility (e.g., polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the incinerator feed, storage of corrosive basic waste, unpermitted RCRA hazardous waste codes).

Selecting waste analysis parameters

- Waste analysis parameters must be selected to represent those characteristics necessary for safe and effective waste management.

- Along with identifying waste analysis parameters, the RCRA regulations require that the WAP provide the rationale for the selection of each parameter.

- Sampling, analytical, and procedural methods that will be used to meet additional waste analysis requirements for specific waste management units must be included, where applicable, in the WAP.

An accurate representation of a waste’s physical and chemical properties is critical in determining viable waste management options. Accordingly, facility waste analysis plans (WAPs) must specify waste parameters that provide sufficient information to ensure:

- Compliance with applicable regulatory requirements (e.g., land disposal restriction regulations, newly identified or listed hazardous wastes),

- Conformance with permit conditions (i.e., ensure that wastes accepted for management fall within the scope of the facility permit, and process performance standards can be met), and

- Safe and effective waste management operations (i.e., ensure that no wastes are accepted that are incompatible or inappropriate given the type of management practices used by the facility).

Criteria for parameter selection

Waste analysis parameters must be selected to represent those characteristics necessary for safe and effective waste management. Due to the diversity of hazardous waste operations and the myriad of operating variables, the identification of the most suitable parameters to be sampled and analyzed can be complex. To this point, relevant waste analysis parameter selection criteria can be developed and reviewed systematically to efficiently identify parameters of interest. Generally, these selection criteria may be organized into the following categories:

- Waste identification,

- Identification of incompatible/inappropriate wastes, and

- Process and design considerations.

Parameter selection process

Waste identification — Identify and classify hazardous wastes generated or managed according to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) waste codes. Determine any additional responsibilities for waste analysis under Land Disposal Restrictions (LDRs) (i.e., verify whether wastes are restricted).

Identify incompatible/inappropriate wastes — Identify appropriate waste analysis parameters to measure ignitability, reactivity, and incompatibility, as well as to identify inappropriate wastes based on facility operations and the profile of waste being managed.

Then, identify the universe of parameters that may be required to evaluate the range of process and design limitations — Determine the specific parameters necessary to identify waste acceptability with respect to process and design limitations, preferably for each management unit. For pre-process, in-process, and post-process operating variables, select parameters which indicate changes in waste composition that may affect waste management (e.g., pH, specific gravity).

Next, evaluate — Eliminate parameters which are duplicate parameters selected during previous parameter selection process elements or cannot be measured due to technological or other limitations.

Rationale for parameter selection

Along with identifying waste analysis parameters, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) regulations require that the WAP provide the rationale for the selection of each parameter. The rationale must describe the basis for the selection of the waste analysis parameter and how it will measure necessary physical and chemical waste properties to afford effective waste management within regulatory, permit, process, and design conditions. This information will provide EPA permit reviewers and WAP users with critical information regarding the viability of parameter selection.

Special parameter selection requirements

WAPs must also include procedures and parameters for complying with the specialized waste management regulatory requirements established for particular hazardous waste management units. These regulatory requirements include special waste analyses for the following:

- Facilities managing ignitable, reactive, or incompatible wastes;

- Landfills;

- Incinerator;

- Treatment, storage, and disposal facility (TSDF) process vents and equipment; and

- Boilers and industrial furnaces.

Sampling, analytical, and procedural methods that will be used to meet additional waste analysis requirements for specific waste management units must be included, where applicable, in the WAP.

Selecting sampling procedures

- To be representative, a sample must be collected and handled by means that will preserve its original physical form and composition, as well as prevent contamination or changes in concentration of the parameters to be analyzed.

Sampling is the physical collection of a representative portion of a universe or whole of a waste or waste treatment residual. To be representative, a sample must be collected and handled by means that will preserve its original physical form and composition, as well as prevent contamination or changes in concentration of the parameters to be analyzed. For a sample to provide meaningful data, it is imperative that it reflect the average properties of the universe from which it was obtained, that its physical and chemical integrity be maintained, and that it be analyzed within a dedicated quality assurance program.

Due to the diversity of hazardous wastes and the number of possible waste management scenarios (e.g., drums, roll-off boxes, tankers, lugger boxes), the type(s) of sampling procedures a facility will need to employ will be variable.

A facility can choose to use sampling methods specified in the regulations in 40 CFR Part 261 Appendix I, or choose to petition the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for equivalent testing and analytical methods. To be successful with this petition, a facility must demonstrate to the satisfaction of EPA that the proposed method is equal, or superior, to the specified method.

Sampling strategies

- Physical and chemical properties of the wastes to be sampled should be taken into consideration since they can influence the sampling development process.

- Two major sampling approaches may be employed to collect representative samples, authoritative sampling or random sampling.

The development and application of a sampling strategy is a prerequisite to obtaining a representative sample capable of producing scientifically viable data. These strategies should be selected or prepared prior to actual sampling to organize and coordinate sampling activities, to maximize data accuracy, and to minimize errors attributable to incorrectly selected sampling procedures. At a minimum, a sampling strategy should address the following:

- Objectives of collecting the samples,

- Types of samples needed (e.g., grab or composite),

- Selection of sampling locations,

- Number of samples,

- Sampling frequency, and

- Sample collection and handling techniques to be used.

In addition, the following factors should also be taken into consideration since they can influence the sampling development process:

- Physical properties of the wastes to be sampled,

- Chemical properties of the wastes to be sampled, and

- Special circumstances or considerations (e.g., complex multi-phasic waste streams, highly corrosive liquids).

Based upon the data objectives and considerations addressed in the sampling strategy, two major sampling approaches may be employed to collect representative samples. These approaches are summarized as follows:

Authoritative sampling. Where sufficient historical, site, and process information is available to accurately assess the chemical and physical properties of a waste, authoritative sampling (also known as judgement sampling) can be used to obtain representative samples. This type of sampling involves the selection of sample locations based on knowledge of waste distribution and waste properties (e.g., homogeneous process streams) as well as management units considerations. Accordingly, the validity of the sampling is dependent upon the accuracy of the information used. The rationale for the selection of sampling locations is critical and should be well documented.

Random sampling. Due to the difficulty of determining the exact chemical and physical properties of hazardous waste streams that are necessary for using authoritative sampling, the most commonly used sampling strategies are random (not to be confused with haphazard) sampling techniques. Generally, three specific techniques — simple, stratified, and systematic random — are employed. By applying these procedures, which are based upon mathematical and statistical theories, representative samples can be obtained from nearly every waste sampling scenario.

Selecting sampling equipment

- Three broad criteria relating to waste should be considered when determining the most appropriate type of sampling equipment to use for a given sampling strategy: physical parameters, chemical parameters, and waste-specific or site-specific factors.

Three broad criteria relating to waste should be considered when determining the most appropriate type of sampling equipment to use for a given sampling strategy:

- Physical parameters. Specific physical parameters affecting this selection include whether the wastes are free flowing or highly viscous liquids; crushed, powdered, or whole solids; contained in soil or groundwater; and homogeneous or heterogeneous, stratified, subject to separation with transport, or subject to other physical alterations due to environmental factors.

- Chemical parameters. The person collecting the sample should ensure that the sampling equipment is constructed of materials that are not only compatible with wastes, but are not susceptible to reactions that might alter or bias the physical or chemical characteristics of the waste.

- Waste-specific (e.g., oily sludges) or site-specific factors (e.g., accessibility issues). In addition to determining the type of sampling equipment used, the waste- and site-specific factors also may require modification of the chosen equipment so that it can be applied to the waste.

Once the physical, chemical, waste- and site-specific factors associated with the waste stream to be sampled have been identified and evaluated, appropriate sampling equipment can be selected. The equipment most typically used in sampling includes:

- Composite liquid waste samplers (coliwasas), weighted bottles, and dippers for liquid waste streams;

- Triers, thieves, and augers for sampling sludges and solid waste streams; and

- Bailers, suction pumps, and positive displacement pumps for sampling wells for groundwater evaluations.

Maintaining and decontaminating field equipment

Some analyses, such as pH, can be performed at the facility using field equipment. This equipment must be properly maintained, and where appropriate, calibrated to ensure data quality from the analyses. Maintenance of equipment can include routine cleaning, oil changes, or routine replacement of worn equipment components. The guidelines set forth in the operator’s manual of each piece of equipment should be followed since proper maintenance varies by model manufacturer. At a minimum, the equipment should be inspected, lubricated, and calibrated prior to any field work to ensure proper operation.

Other sampling considerations

- Low concentration samples require sample preservation, unlike most highly concentrated samples.

- Safety and health considerations should be taken into consideration when conducting sampling at the facility.

Sample preservation and storage

Once the sample has been collected, sample preservation techniques, if applicable, must be employed to ensure that the integrity of the waste remains intact while the samples are in transport to the laboratory and/or while temporarily stored at the laboratory prior to analysis. Sample preservation is generally not applicable for highly concentrated samples. However, low concentration samples require preservation.

Establishing quality assurance/quality control procedures

Quality assurance (QA) is the process for ensuring that all data and the decisions based on that data are technically sound, statistically valid, and properly documented. Quality control (QC) procedures are the tools employed to measure the degree to which these quality assurance objectives are fulfilled. As the first component of data acquisition in relation to waste analysis, sampling techniques should incorporate rigorous QA/QC procedures to ensure the validity of sampling activities. Thus, it is important for QA/ QC procedures to be established in the waste analysis plan (WAP) and stringently followed.

Establishing health and safety protocols

Safety and health considerations should be taken into consideration when conducting sampling at the facility. Employees who perform sampling activities must be properly trained with respect to the hazards associated with waste materials, as well as with any waste handling procedures that will assist in protecting the health and safety of the sampler.

In addition, the employees must be trained in the proper protective clothing and equipment that must be used when performing sampling activities.

Selecting testing and analytical methods

- Analytical methods consist of two distinct phases — a preparation phase and a determination phase.

- The analytical laboratory that a facility selects should exhibit demonstrated experience and capabilities in three major areas: comprehensive QA/QC programs, technical analytical expertise, and effective information management systems.

To be useful in sustaining regulatory and permit compliance, the waste analysis plan (WAP) must specify testing and analytical methods which are capable of providing reliable data to ensure safe and effective waste management. The selection of an appropriate methodology is dependent upon the following considerations:

- Physical state of the sample (e.g., solid or liquid),

- Analytes of interest (e.g., volatile organics),

- Required detection limits (e.g., 1/5 to ½ of the regulatory thresholds),and

- Information requirements (e.g., detection monitoring, verify compliance with Land Disposal Restriction (LDR) treatment standards).

Analytical methods consist of two distinct phases — a preparation phase and a determination phase. The use of an appropriate combination of preparation and determination procedures is necessary to ensure the accuracy of data generated from the facility waste management program.

In addition to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Publication SW-846, the following references provide information on approved methods for analyzing waste samples:

- American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM)

- “Design and Development of a Hazardous Waste Reactivity Testing Protocol,” EPA Document No. 600/2-84-057 (February 1984)

- “The Toxicity Characteristic Rule” (55 FR 11862)

- “Methods for Chemical Analysis of Water and Wastes,” EPA Document No. 600/4- 79-020 (Revised March 1983).

Selecting a laboratory

The use of proper analytical procedures is essential to acquiring useful and accurate data. Obtaining accurate results requires an analytical laboratory that has demonstrated experience in performing waste sample analyses. When selecting a laboratory, preference should be given to those that are capable of providing documentation of their proven analytical capabilities, available instrumentation, and standard operating procedures. Furthermore, the laboratory should be able to substantiate their data by systematically documenting the steps taken to obtain and validate the data.

The analytical laboratory that a facility selects should exhibit demonstrated experience and capabilities in three major areas:

- Comprehensive quality assurance/quality control programs (both qualitative and quantitative);

- Technical analytical expertise; and

- Effective information management systems.

Selecting waste re-evaluation frequencies

- Although there are no required time intervals for re-evaluating wastes, a facility must develop a schedule for re-evaluating the waste on a regular basis.

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) regulations state that “waste analysis must be repeated as often as necessary to ensure that it is accurate and up to date.” At a minimum, the analysis must be repeated as follows:

- When the treatment, storage, and disposal facility (TSDF) is notified, or has reason to believe that the process or operation generating the hazardous wastes has changed;

- When the generator has been notified by an offsite TSDF that the characterization of the wastes received at the TSDF does not match a pre-approved waste analysis certification and/or the accompanying waste manifest or shipping paper (the generator may be requested to re-evaluate the waste); and

- Offsite combustion facilities should characterize all wastes prior to burning to verify that permit conditions will be met (i.e., fingerprint analysis may not be acceptable).

Although there are no required time intervals for re-evaluating wastes, a facility must develop a schedule for re-evaluating the waste on a regular basis. A facility will need to make an individual assessment of how often the wastes analysis is necessary to ensure compliance with interim status or Part B permit operating conditions.

Fingerprint analysis is never a substitute for conducting a complete waste analysis and, therefore, may not be defensible if a waste is misidentified by the generator and passes the fingerprint test. Though the generator is responsible for properly identifying and classifying the waste, the TSDF will be held liable by enforcement authorities if it violates its permit conditions and any other applicable regulations. The decision to conduct abbreviated corroborative testing using fingerprint analysis on a few select parameters, or to conduct a complete analysis to verify the profile, is ultimately determined by the offsite facility with this in mind.

Hazardous waste generator categories

- There are three categories of hazardous waste generators: VSQGs, SQGs, and LQGs.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) hazardous waste regulations apply differently depending upon a facility’s generator category, which is determined by how much hazardous waste the facility generates each month. The more waste a facility generates, the more regulated the facility is.

There are three categories of hazardous waste generators:

- Very small quantity generators (VSQGs, formerly known as conditionally exempt small quantity generators);

- Small quantity generators (SQGs); and

- Large quantity generators (LQGs).

VSQGs generate the least amount of hazardous waste per month and LQGs generate the most. Generators must comply with a specific set of requirements for their specific generator category.

Cited under 40 CFR 261, 262.14, 262.16, and 262.17, hazardous waste generators are required to:

- Count the total amount of hazardous waste generated in a calendar month.

- Determine their hazardous waste generator category (i.e., VSQG, SQG, or LQG).

- Not accumulate more waste than is allowed for their generator category at any one time.

- Ship waste offsite within 180 or 90 days, depending on the generator category.

- Notify EPA of their waste activities and obtain an EPA ID Number (SQGs and LQGs only).

- Manage the waste according to their hazardous waste generator category.

- Know what to do if they exceed their accumulation limits.

Conditions for exemption vs. independent requirements

Conditions for exemption: These are conditions generators must meet in order to manage hazardous waste at their facilities without having to obtain a permit as a treatment, storage, or disposal facility (TSDF). The legal consequence of not complying with a condition for exemption is that the generator who accumulates waste onsite can be charged with operating a non-exempt storage facility (unless it is meeting the conditions for exemption of a larger generator category). A generator operating a storage facility without any exemption is subject to, and potentially in violation of, many storage permit and operations requirements in Parts 124, 264 through 268, and 270. Example: The 90-day accumulation time limit for large quantity generators.

Independent requirements: These requirements apply to generators regardless of whether they choose to obtain an exemption from the permit requirement. An independent requirement is equivalent to a law that can be broken. EPA can pursue an enforcement action against a generator for violating an independent requirement. Example: Pre-transport waste packaging requirements are unconditional demands. Failure to meet these requirements would result in penalties or fines.

Determining generator category

- Monthly totals will determine a facility’s generator category.

- Don’t include exempted wastes, used oil, universal waste, residue from empty containers, or waste that has already been counted in waste calculations.

- The three waste generator categories have different accumulation time limits.

A facility must count all the hazardous waste generated each month toward the monthly generator totals. This includes any acutely hazardous waste and waste generated at satellite accumulation areas. The monthly totals will determine a facility’s generator category.

Measure monthly hazardous waste generation in the following steps:

- Perform generator calculations on the first day of each month.

- Calculate the weight of all full hazardous waste containers placed into storage during the prior month.

- Calculate the weight in pounds or kilograms.

- Add the weight of all the waste in satellite accumulation containers in satellite accumulation areas and then subtract from this amount the weight of the prior month’s satellite containers.

Don’t include the following in waste calculations:

- Exempted wastes

- Used oil (unless the facility manages it as a hazardous waste)

- Universal waste

- Residue from “empty containers”

- Waste that has already been counted

Accumulation quantity and time limits

Waste accumulation is not the same thing as waste generation. Accumulation refers to how much hazardous waste a facility has onsite at any one time. The higher the generation category, the more waste a facility can accumulate (but the less time a facility has to accumulate it).

Note that as a generator, a facility does not really store waste. Generators may accumulate the waste onsite without having to get a permit to store hazardous waste — as long as they comply with all of the management conditions. If a facility does not comply with the management conditions, then the generator could be considered a storage facility (which requires a permit).

The three waste generator categories have different accumulation time limits. Stay within the time limits for the category.

- Very small quantity generators (VSQGs) may accumulate up to 2,200 pounds (or up to 2.2 pounds of acutely hazardous waste) onsite, but they have no time limit for shipping the waste offsite. Most waste experts will say not to keep waste onsite for more than one year.

- Small quantity generator (SQGs) may accumulate up to 13,000 pounds at any one time and they must ship waste offsite within 180 days — roughly six months. If an SQG will ship the waste more than 200 miles, they have up to 270 days to do it. This is because in some areas of the country, properly permitted hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facilities are hard to come by.

- Large quantity generators (LQGs) have no accumulation limit — but they only have 90 days to ship their waste offsite.

Very small quantity generators (VSQGs)

- VSQGs do not have to apply for EPA ID Numbers, comply with federal storage requirements, or use a hazardous waste manifest.

- HWGIR allows VSQGs to ship waste to an LQG that is under the control of the same person.

Very small quantity generators (VSQGs) used to be called “conditionally exempt small quantity generators” and are minimally regulated. They can only generate:

- Up to 220 pounds of hazardous waste per month;

- Up to 2.2 pounds of acutely hazardous waste per month; or

- Up to 220 pounds of acute spill residue or soil per month.

VSQGs do not have to apply for Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Identification (ID) Numbers, comply with federal storage requirements, or use a hazardous waste manifest.

Basic requirements for VSQGs are:

- Identify all hazardous waste generated.

- Do not accumulate more than 2,200 pounds of hazardous waste at any time.

- Ensure that hazardous waste is delivered to a person or facility authorized to manage it.

Be sure to check the state-level requirements in this area. Remember, any state can pass more stringent regulations than the federal ones. Many states have more stringent requirements for VSQGs, including requiring manifests for waste shipments from these generators.

VSQG waste sent to large quantity generators (LQGs)

EPA’s 2016 rule known as the Hazardous Waste Generator Improvements Rule (HWGIR) simplified the shipping of VSQG waste offsite. The HWGIR allows VSQGs to ship waste to an LQG that is under the control of the same person. EPA says this will reduce the overall time that the VSQG accumulates hazardous waste onsite, thus better protecting the environment. (Note that not all states allow this practice.)

The VSQG must mark containers of hazardous waste sent to LQGs with:

- The words “Hazardous Waste” and

- An indication of the hazards of the contents.

Small quantity generators (SQGs)

- SQGs generate between 220 and 2,200 pounds of hazardous waste per month.

Small quantity generators (SQGs) generate between 220 and 2,200 pounds of hazardous waste per month, 2.2 pounds or less of acute hazardous waste, and 220 pounds or less of residues from a cleanup of acute hazardous waste generated in a calendar month. They are more regulated than very small quantity generators (VSQGs), but less regulated than large quantity generators (LQGs).

Basic requirements for SQGs are:

- Identify all hazardous waste generated.

- Obtain an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Hazardous Waste Generator ID number.

- Ship waste offsite within 180 days (or 270 days if shipping a distance greater than 200 miles).

- Do not accumulate more than 13,000 pounds of waste onsite at any one time.

- Ensure there is always at least one employee available to respond to an emergency. This employee is the emergency coordinator responsible for coordinating all emergency response measures. SQGs are not required to have detailed, written contingency plans.

- Store waste in proper containers (no leaks, bulges, etc.).

- Properly mark and label waste containers.

- Train employees in basic waste management and emergency procedures.

- Ship waste offsite using the hazardous waste manifest.

- Submit annual waste report to state (if required) and submit SQG re-notification every four years beginning in 2021. This is a recent requirement under the Hazardous Waste Generator Improvements Rule (HWGIR).

Large quantity generators (LQGs)

- LQGs produce more than 2,200 pounds of hazardous waste, or more than 2.2 pounds of acutely hazardous waste, per month.

The largest hazardous waste generators, large quantity generators (LQGs) are also the most regulated. These generators produce more than 2,200 pounds of hazardous waste, or more than 2.2 pounds of acutely hazardous waste per month, or more than 220 pounds of residues from a cleanup of acute hazardous waste. LQGs do not have a limit on the amount of hazardous waste accumulated onsite.

Basic requirements for LQGs are:

- Identify all hazardous wastes generated.

- Obtain an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Hazardous Waste Generator ID number.

- Ship waste offsite within 90 days.

- Ensure there is at least one employee available to respond to an emergency at all times. This employee is the emergency coordinator responsible for coordinating all emergency response measures.

- Develop detailed, written contingency plans for handling emergencies and prepare a summary of these plans for emergency responders.

- Follow all accumulation and storage requirements, such as labeling containers, using proper containers, inspecting waste accumulation areas, etc.

- Train employees in their job-specific waste management duties along with all emergency procedures.

- Ship waste offsite using the hazardous waste manifest.

- Submit a biennial hazardous waste report to EPA or the state every even-numbered year.

The Hazardous Waste Generator Improvements Rule

- HWGIR made over 60 changes to the hazardous waste management regulations.

In 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Hazardous Waste Generator Improvements Rule (HWGIR) made over 60 changes to the hazardous waste management regulations. One of the goals of the rule is to make the numerous and complex regulations easier to read and follow. EPA did this by reorganizing and rearranging the regulations that apply to hazardous waste generators into a more user-friendly format.

A few of EPA’s revisions to the regulations allow generators more flexibility and options for managing their hazardous waste. For instance, very small quantity generators (VSQGs) will be able to send their hazardous waste to a large quantity generator in control of the same person (i.e., common control) to consolidate it before sending it for disposal. This option could save the company time and money in shipping and disposing hazardous waste.

Also, smaller generators may be able to maintain their existing generator categories, even if they experience an “episodic” waste generation event. In the past, when VSQGs or small quantity generators (SQGs) exceeded their monthly hazardous waste quantity limits, they would automatically bump up to a more regulated generator category. Under the HWGIR, smaller generators can remain in their less regulated categories if they meet certain conditions.

But the HWGIR doesn’t just make things easier for facilities. EPA did impose some new, and stricter, compliance obligations on waste generators. Be sure to check state regulations to verify whether the state has adopted the more relaxed provisions of HWGIR — however, any stricter provisions at the federal level must be met by all generators.

Episodic generation

- Most episodic generators manage all of their wastes to comply with the larger generator category requirements in order to make things less complicated.

- EPA is allowing VSQGs and SQGs to have one planned and one unplanned episodic event per year.

- The generator must notify EPA at least 30 calendar days before beginning a planned episodic event or within 72 hours after an unplanned event.

Some generators regularly switch categories. This may be because they have more wastes during certain times of the year or they conduct a yearly lab cleanout or other yearly disposal effort. In other cases, the discovery of an unknown waste or a tank malfunction may cause an unexpected waste generation that pushes the generator into a higher generator category. Whatever the cause, this kind of generation is known as “episodic generation.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says that a facility may be subject to different standards at different times, depending on the generator category in a given month. If a facility generates less than 220 pounds of hazardous waste in one calendar month, the facility would be a very small quantity generator (VSQG); however, if in the next month, the facility generates 300 pounds of hazardous waste, then the facility would be a small quantity generator (SQG) — at least for as long as the waste generated in that month is onsite.