['Waste']

['Incinerators']

11/22/2023

...

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

40 CFR Parts 60, 63, 260, 261, 264, 265, 266, 270, and 271

[FRL-5447-2]

RIN 2050-AF01

Revised Standards for Hazardous Waste Combustors

AGENCY: Environmental Protection Agency.

ACTION: Proposed rule.

SUMMARY: The Agency is proposing revised standards for hazardous waste incinerators, hazardous waste-burning cement kilns, and hazardous waste-burning lightweight aggregate kilns. These standards are being proposed under joint authority of the Clean Air Act (CAA) and Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). The standards limit emissions of chlorinated dioxins and furans, other toxic organic compounds, toxic metals, hydrochloric acid, chlorine gas, and particulate matter. These standards reflect the performance of Maximum Achievable Control Technologies (MACT) as specified by the Clean Air Act. The MACT standards also should result in increased protection to human health and the environment over existing RCRA standards. The nature of this proposal requires that the following actions also be proposed: proposing the addition of hazardous waste-burning lightweight aggregate kilns to the list of source categories in accordance with 112(c)(5) of the Act; exempting from RCRA emission controls secondary lead facilities subject to MACT; considering an exclusion for certain "comparable fuels"; and revising the small quantity burner exemption under the BIF rule.

DATES: EPA will accept public comments on this proposed rule until June 18, 1996.

ADDRESSES: Commenters must send an original and two copies of their comments referencing docket number F-96-RCSP-FFFFF to: RCRA Docket Information Center, Office of Solid Waste (5305W), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Headquarters (EPA, HQ), 401 M Street, SW., Washington, DC 20460. Deliveries of comments should be made to the Arlington, VA, address listed below. Comments may also be submitted electronically through the Internet to: RCRA-Docket@epamail.epa.gov. Comments in electronic format should also be identified by the docket number F-96-RCSP-FFFFF. All electronic comments must be submitted as an ASCII file avoiding the use of special characters and any form of encryption.

Commenters should not submit electronically any Confidential Business Information (CBI). An original and two copies of CBI must be submitted under separate cover to: RCRA CBI Document Control Officer, Office of Solid Waste (5305W), U.S. EPA, 401 M Street, SW, Washington, DC 20460.

Public comments and supporting materials are available for viewing in the RCRA Information Center (RIC), located at Crystal Gateway One, 1235 Jefferson Davis Highway, First Floor, Arlington, VA. The RIC is open from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., Monday through Friday, excluding federal holidays. To review docket materials, the public must make an appointment by calling (703) 603-9230. The public may copy a maximum of 100 pages from any regulatory docket at no charge. Additional copies cost $.15/page. The index and some supporting materials are available electronically. See the "Supplementary Information" section for information on accessing them.

A public hearing will be held, if requested, to discuss the proposed standards for hazardous waste combustors, in accordance with section 307(d)(5) of the Act. Persons wishing to make an oral presentation at a public hearing should contact the EPA at the address given in the ADDRESSES section of this preamble. Oral presentations will be limited to 5 minutes each, unless additional time is feasible. Any member of the public may file a written statement before, during, or within 30 days after the hearing. Written statements should be addressed to the RCRA Docket Section address given in the ADDRESSES section of this preamble and should refer to Docket No. F-96-RCSP-FFFFF. A verbatim transcript of the hearing and written statements will be available for public inspection and copying during normal working hours at the EPA's RCRA Docket Section in Washington, D.C. (see ADDRESSES section of this preamble).

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: For general information, contact the RCRA Hotline at 1-800-424-9346 or TDD 1-800-553-7672 (hearing impaired). In the Washington metropolitan area, call 703-412-9810 or TDD 703-412-3323.

For more detailed information on specific aspects of this rulemaking, contact Larry Denyer, Office of Solid Waste (5302W), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 401 M Street, SW., Washington, DC 20460, (703) 308-8770, electronic mail: Denyer.Larry@epamail.epa.gov. For more detailed information on implementation of this rulemaking, contact Val de la Fuente, Office of Solid Waste (5303W), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 401 M Street, SW., Washington, DC 20460, (703) 308-7245, electronic mail: DeLaFuente.Val@epamail.epa.gov. For more detailed information on regulatory impact assessment of this rulemaking, contact Gary Ballard, Office of Solid Waste (5305), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 401 M Street, SW., Washington, DC 20460, (202) 260-2429, electronic mail: Ballard.Gary@epamail.epa.gov. For more detailed information on risk analyses of this rulemaking, contact David Layland, Office of Solid Waste (5304), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 401 M Street, SW., Washington, DC 20460, (202) 260-4796, electronic mail: Layland.David@epamail.epa.gov.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The index and the following supporting materials are available on the Internet: (List documents) Follow these instructions to access the information electronically: Gopher: gopher.epa.gov WWW: http://www.epa.gov Dial-up: (919) 558-0335.

This report can be accessed off the main EPA Gopher menu, in the directory: EPA Offices and Regions/Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response (OSWER)/Office of Solid Waste (RCRA)/(consult with Communication Strategist for precise subject heading)

FTP: ftp.epa.gov

Login: anonymous

Password: Your Internet address

Files are located in /pub/gopher/OSWRCRA

The official record for this action will be kept in paper form. Accordingly, EPA will transfer all comments received electronically into paper form and place them in the official record, which will also include all comments submitted directly in writing. The official record is the paper record maintained at the address in ADDRESSES at the beginning of this document.

EPA responses to comments, whether the comments are written or electronic, will be in a notice in the Federal Register or in a response to comments document placed in the official record for this rulemaking. EPA will not immediately reply to commenters electronically other than to seek clarification of electronic comments that may be garbled in transmission or during conversion to paper form, as discussed above.

Glossary of Acronyms

APCD—Air Pollution Control Device

BDAT—Best Demonstrated Available Technology

BIFs—Boilers and Industrial Furnaces

BTF—Beyond-the-Floor

CAA—Clean Air Act

Cl2—Chlorine

CO—Carbon Monoxide

D/F—Dioxins/Furans

D/O/M—Design/Operation/Maintenance

ESP—Electrostatic Precipitator

EU—European Union

FF—Fabric Filter

HAP—Hazardous Air Pollutant

HC—Hydrocarbons

HCl—Hydrochloric acid

Hg—Mercury

HHE—Human Health and the Environment

HON—Hazardous Organic NESHAPs

HSWA—Hazardous and Solid Waste Amendments

HWC—Hazardous Waste Combustion/Combustor

ICR—Information Collection Request

LDR—Land Disposal Restrictions

LVM—Low-volatile Metals

LWAK—Lightweight Aggregate Kiln

MACT—Maximum Achievable Control Technology

MTEC—Maximum Theoretical Emission Concentration

NESHAPs—National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants

PM—Particulate Matter

PICs—Products of Incomplete Combustion

RCRA—Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

RIA—Regulatory Impact Assessment

SVM—Semivolatile Metals

TCLP—Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure

UTS—Universal Treatment Standards

Part One: Background

- Overview

- Relationship of Today's Proposal to EPA's Waste Minimization National Plan

Part Two: Devices That Would Be Subject To The Proposed Emission Standards

- Hazardous Waste Incinerators

- Overview

- Summary of Major Incinerator Designs

- Number of Incinerator Facilities

- Typical Emission Control Devices For Incinerators

- Hazardous Waste-Burning Cement Kilns

- Overview of Cement Manufacturing

- Summary of Major Design and Operating Features of Cement Kilns

- Number of Facilities

- Emissions Control Devices

- Hazardous Waste-Burning Lightweight Aggregate Kilns

- Overview of Lightweight Aggregate Kilns (LWAKs)

- Major Design and Operating Features

- Number of Facilities

- Air Pollution Control Devices

Part Three: Decision Process for Setting National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAPs)

- Source of Authority for NESHAP Development

- Procedures and Criteria for Development of NESHAPs

- List of Categories of Major and Area Sources

- Clean Air Act Requirements

- Hazardous Waste Incinerators

- Cement Kilns

- Lightweight Aggregate Kilns

- Proposal to Subject Area Sources to the NESHAPs under Authority of Section 112(c)(6)

- Selection of MACT Floor for Existing Sources

- Proposed Approach: Combined Technology-Statistical Approach

- Another Approach Considered But Not Used

- Identifying Floors as Proposed in CETRED

- Establishing Floors One HAP or HAP Group at a Time

- Selection of Beyond-the-Floor Levels for Existing Sources

- Selection of MACT for New Sources

- RCRA Decision Process

- RCRA and CAA Mandates to Protect Human Health and the Environment

- Evaluation of Protectiveness

- Use of Site-Specific Risk Assessments under RCRA

Part Four: Rationale for Selecting the Proposed Standards

- Selection of Source Categories and Pollutants

- Selection of Sources and Source Categories

- Selection of Pollutants

- Applicability of the Standards Under Special Circumstances

- Selection of Format for the Proposed Standards

- Format of the Standard

- Averaging Periods

- Incinerators: Basis and Level for the Proposed NESHAP Standards for New and Existing Sources

- Summary of MACT Standards for Existing Incinerators

- Summary of MACT Standards For New Incinerators

- Evaluation of Protectiveness

- Cement Kilns: Basis and Level for the Proposed NESHAP Standards for New and Existing Sources

- Summary of Standards for Existing Cement Kilns

- MACT for New Hazardous Waste-Burning Cement Kilns

- Evaluation of Protectiveness

- Lightweight Aggregate Kilns: Basis and Level for the Proposed NESHAP Standards for New and Existing Sources

- Summary of MACT Standards for Existing LWAKs

- MACT for New Sources

- Evaluation of Protectiveness

- Achievability of the Floor Levels

- Comparison of the Proposed Emission Standards With Emission Standards for Other Combustion Devices

- Alternative Floor (12 Percent) Option Results

- Summary of Results of 12 Percent Analysis

- Summary of MACT Floor Cost Impacts and Emissions Reductions

- Alternative Floor Option: Percent Reduction Refinement

- Additional Data for Comment

Part Five: Implementation

- Selection of Compliance Dates

- Existing Sources

- New Sources

- One year extensions for Pollution Prevention/Waste Minimization

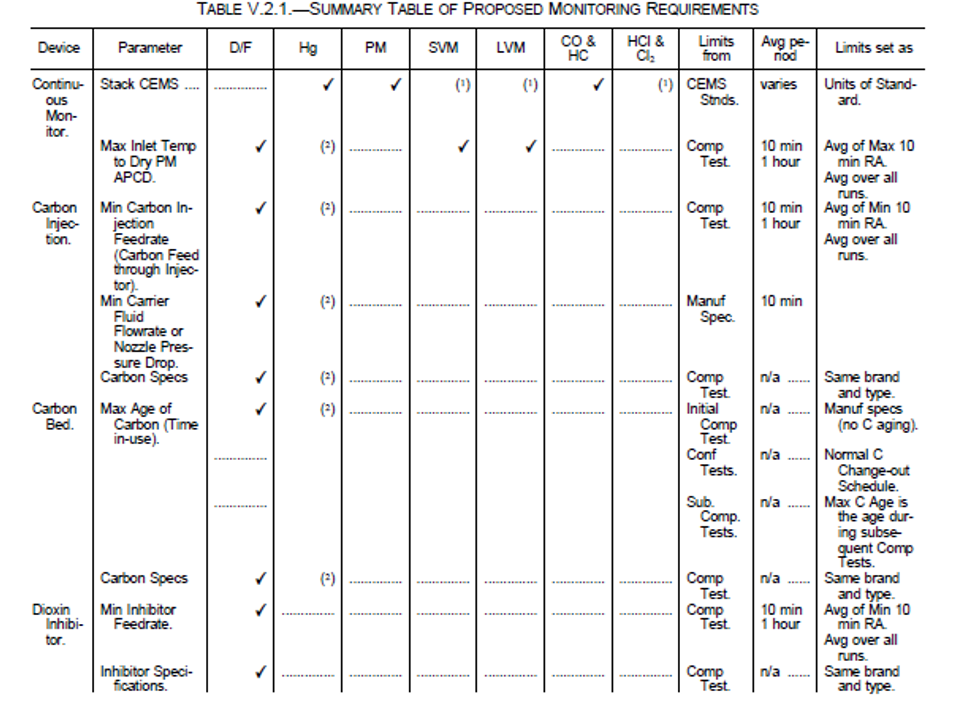

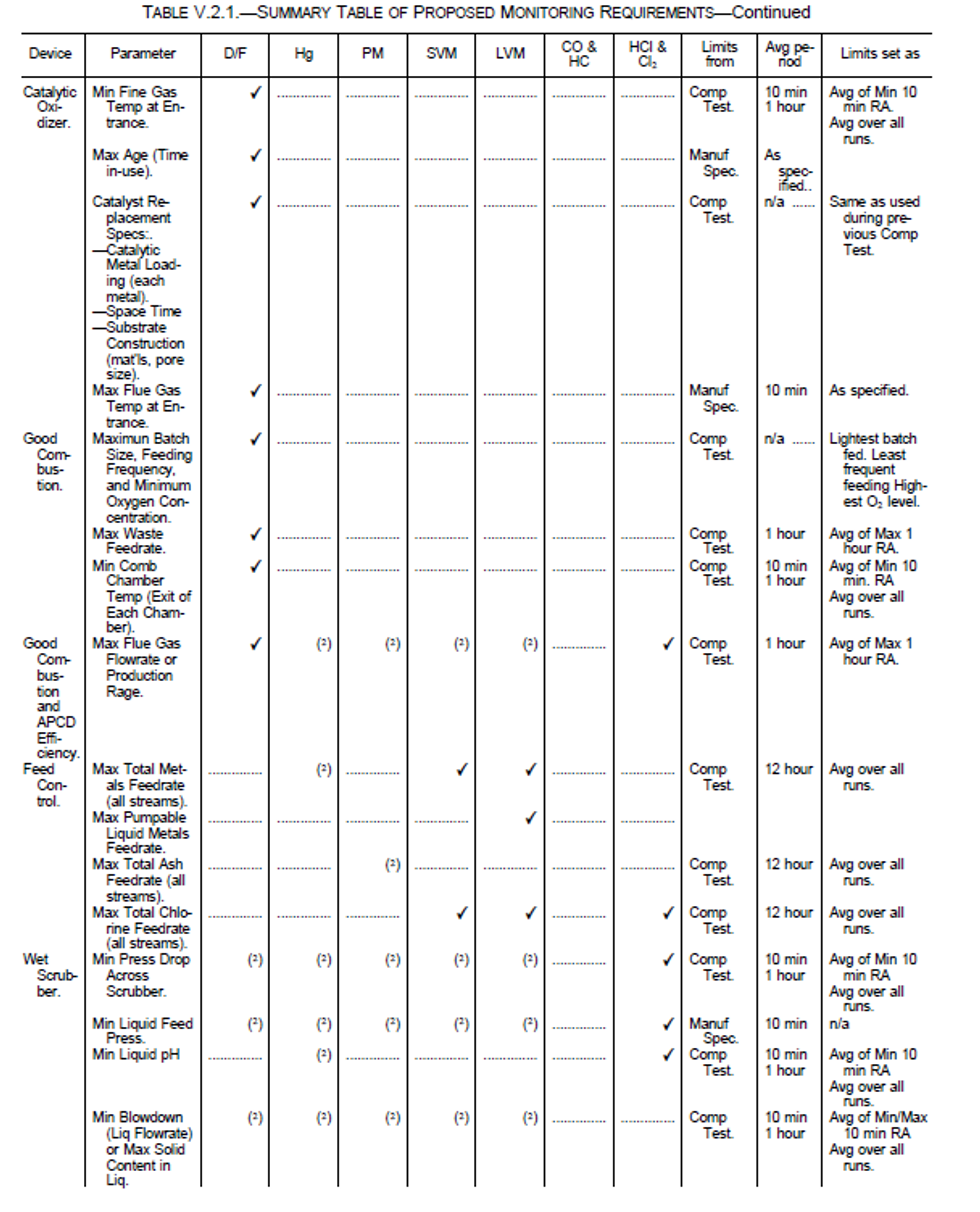

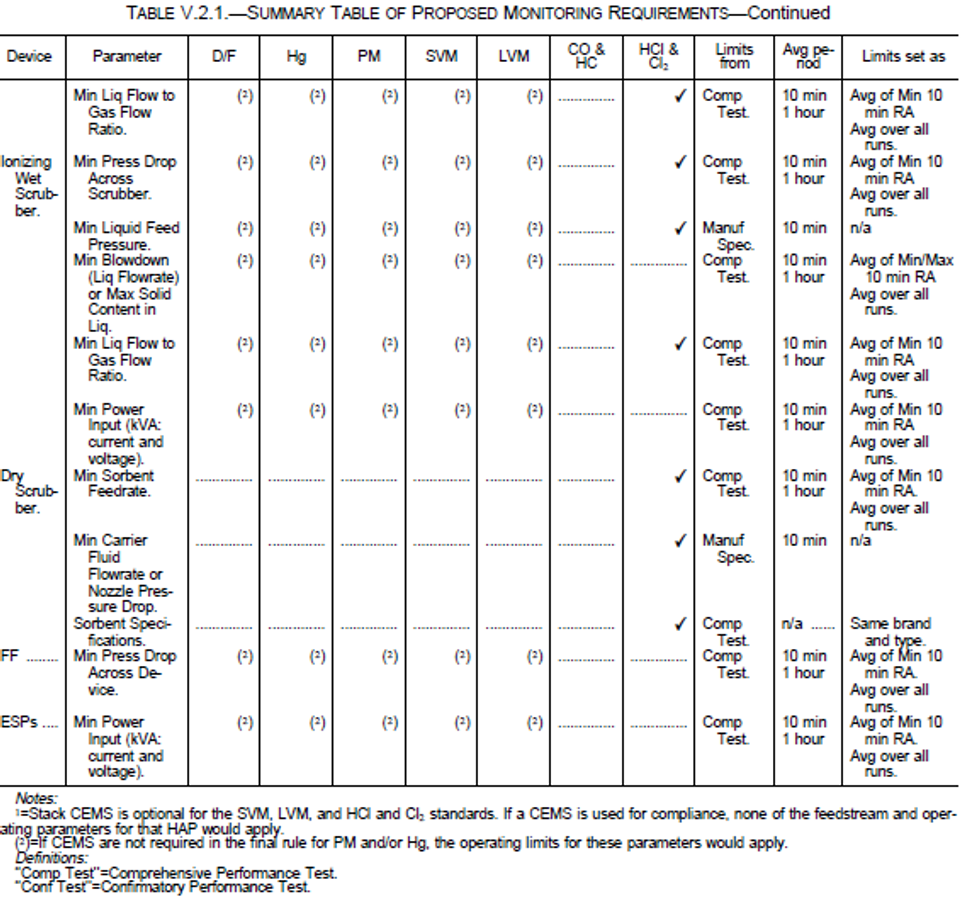

- Selection of Proposed Monitoring Requirements

- Monitoring Hierarchy

- Use of Comprehensive Performance Test Data to Establish Operating Limits

- Compliance Monitoring Requirements

- Combustion Fugitive Emissions

- Automatic Waste Feed Cutoff (AWFCO) Requirements and Emergency Safety Vent (ESV) Openings

- Quality Assurance for Continuous Monitoring Systems

- MACT Performance Testing and Related Issues

- MACT Performance Testing

- RCRA Trial Burns

- Waiver of MACT Performance Testing for HWCs Feeding De Minimis Levels of Metals or Chlorine

- Relative Accuracy Tests for CEMS

- Selection of Manual Stack Sampling Methods

- Notification, Recordkeeping, Reporting, and Operator Certification Requirements

- Notification Requirements

- Reporting Requirements

- Recordkeeping Requirements

- Permit Requirements

- Coordination of RCRA and CAA Permitting Processes

- Permit Application Requirements

- Clarifications on Definitions and Permit Process Issues

- Pollution Prevention/Waste Minimization Options

- Permit Modifications Necessary to Come Into Compliance With MACT Standards

- State Authorization

- Authority for Today's Rule

- Program Delegation Under the Clean Air Act

- RCRA State Authorization

- Definitions

- Definitions Proposed in §63.1201

- Conforming Definitions Proposed in §§260.10 and 270.2

- Clarification of RCRA Definition of Industrial Furnace

Part Six: Miscellaneous Provisions and Issues

- Comparable Fuel Exclusion

- EPA's Approach to Establishing Benchmark Constituent Levels

- Sampling, Analysis, and Statistical Protocols Used

- Options for the Benchmark Approach

- Comparable Fuel Specification

- Exclusion of Synthesis Gas Fuel

- Implementation of the Exclusion

- Transportation and Storage

- Speculative Accumulation

- Regulatory Impacts

- Miscellaneous Revisions to the Existing Rules

- Revisions to the Small Quantity Burner Exemption under the BIF Rule

- The Waiver of the PM Standard under the Low Risk Waste Exemption of the BIF Rule Would Not Be Applicable to HWCs

- The "Low Risk Waste" Exemption from the Emission Standards Provided by the Existing Incinerator Standards Would Be Superseded by the MACT Rules

- Bevill Residues

- Applicability of Regulations to Cyanide Wastes

- Shakedown Concerns

- Extensions of Time Under Certification of Compliance

- Technical Amendments to the BIF Rule

- Clarification of Regulatory Status of Fuel Blenders

- Change in Reporting Requirements for Secondary Lead Smelters Subject to MACT

Part Seven: Analytical and Regulatory Requirements

- Executive Order 12866

- Regulatory Options

- Assessment of Potential Costs and Benefits

- Introduction

- Analysis and Findings

- Total Incremental Cost per Incremental Reduction in HAP Emissions

- Human Health Benefits

- Other Benefits

- Other Regulatory Issues

- Environmental Justice

- Unfunded Federal Mandates

- Regulatory Takings

- Incentives for Waste Minimization and Pollution Prevention

- Regulatory Flexibility Analysis

- Paperwork Reduction Act

- Request for Data Appendix—Comparable Fuel Constituent and Physical Specifications

- PART 60—STANDARDS OF PERFORMANCE FOR NEW STATIONARY SOURCES

- PART 63—NATIONAL EMISSION STANDARDS FOR HAZARDOUS AIR POLLUTANTS FOR SOURCE CATEGORIES

- PART 260—HAZARDOUS WASTE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM: GENERAL

- PART 261—IDENTIFICATION AND LISTING OF HAZARDOUS WASTE

- PART 264—STANDARDS FOR OWNERS AND OPERATORS OF HAZARDOUS WASTE TREATMENT, STORAGE, AND DISPOSAL FACILITIES

- PART 265—INTERIM STATUS STANDARDS FOR OWNERS AND OPERATORS OF HAZARDOUS WASTE TREATMENT, STORAGE, AND DISPOSAL FACILITIES

- PART 266—STANDARDS FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SPECIFIC HAZARDOUS WASTES AND SPECIFIC TYPES OF HAZARDOUS WASTE MANAGEMENT FACILITIES

- PART 270—EPA ADMINISTERED PERMIT PROGRAMS: THE HAZARDOUS WASTE PERMIT PROGRAM

- PART 271—REQUIREMENTS FOR AUTHORIZATION OF STATE HAZARDOUS WASTE PROGRAMS

PART ONE: BACKGROUND

I. Overview

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is proposing to revise standards for hazardous waste incinerators and hazardous waste-burning cement kilns and lightweight aggregate kilns (LWAKs) under joint authority of the Clean Air Act, as amended, (CAA) and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, as amended (RCRA). The emission standards in today's proposal have been developed under the CAA provisions concerning the maximum level of achievable control over hazardous air pollutants (HAPs), taking into consideration the cost of achieving the emission reduction, any non-air quality health and environmental impacts, and energy requirements. These maximum achievable control technology (MACT) standards, also referred to as National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAPs), are proposed in today's rule for the following HAPs: dioxins/furans, mercury, two semivolatile metals (lead and cadmium), four low volatility metals (antimony, arsenic, beryllium, and chromium), particulate matter, and hydrochloric acid/chlorine gas. Other toxic organic emissions are addressed by standards for carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrocarbons (HC).

This action is being taken for several reasons. First, this proposal is consistent with the terms of the 1993 settlement agreement between the Agency and a number of groups who challenged EPA's final RCRA rule entitled "Burning of Hazardous Waste in Boilers and Industrial Furnaces" (56 FR 7134, Feb. 21, 1991). These groups include the Natural Resources Defense Council, Sierra Club, Inc., Hazardous Waste Treatment Council (now the Environmental Technology Council), National Solid Waste Management Association, and a number of local citizens' groups. Under this settlement agreement, the Agency is to propose this rulemaking by September-November, 1995, and finalize it by December 1996.

Second, EPA has scheduled rulemakings to develop maximum achievable control technology (MACT) standards for hazardous waste incinerators and cement kilns. To minimize the burden on the Agency and the regulated community, the Agency has combined its efforts under the CAA and RCRA into one rulemaking to establish MACT standards, which also would satisfy the RCRA settlement agreement obligations.

Third, the Agency's Hazardous Waste Minimization and Combustion Strategy, first announced in May 1993, in addition to stressing waste minimization, also made a commitment to upgrade the emission standards for hazardous waste-burning facilities. The three categories of facilities covered in this proposal burn over 80 percent of the total amount of hazardous waste being combusted each year. [The remaining 15-20 percent is burned in industrial boilers and other types of industrial furnaces, which are to be addressed in the next rulemaking for which a proposal is to be issued by December 1998 or sooner.]

Finally, as relates to the development of revised standards under concurrent Clean Air Act and RCRA authority, most of these hazardous waste combustion facilities are major sources of HAP emissions. They therefore must be regulated under section 112(d) of the Clean Air Act. In addition, EPA noted, when promulgating the RCRA rules for boilers and industrial furnaces in 1991 and in a proposal to revise the incinerator rules, that existing standards did not fully consider the possibility of exposure via indirect (non-inhalation) exposure pathways. 56 FR at 7150, 7167, 7169-70 (Feb. 21, 1991); 54 FR at 43720-21, 43723, 43757 (Oct. 26, 1989). The Agency reiterated these concerns in the Combustion Strategy announced in 1993 as one of the major factors leading to its decision to undertake revisions to the standards for hazardous waste combustors. As also noted in the Combustion Strategy and elsewhere, site-specific RCRA omnibus authority, whereby permit writers can impose additional conditions as are necessary to protect human health and the environment, can be used to buttress the existing regulations. See, e.g., 56 FR 7145, at n.8. Nevertheless, this process is expensive, time-consuming, and not always sufficiently certain in result. The Agency thus indicated, in the Combustion Strategy, that technology-based standards could provide a superior means of control by providing certainty of operating performance.

Because of the joint authorities under which this rule is being proposed, the proposal also contains an implementation scheme that is intended to harmonize the RCRA and CAA programs to the maximum extent permissible by law. In pursuing a common-sense approach towards this objective, the proposal seeks to establish a framework that: (1) Provides for combined (or at least coordinated) CAA and RCRA permitting of these facilities; (2) allows maximum flexibility for regional, state, and local agencies to determine which of their resources will be used for permitting, compliance, and enforcement efforts; and (3) integrates the monitoring, compliance testing, and recordkeeping requirements of the CAA and RCRA so that facilities will be able to avoid two potentially different regulatory compliance schemes.

In addition, this proposal addresses the variety of issues, to the extent appropriate at this time, raised in several petitions filed with the Agency. These petitions are from the Cement Kiln Recycling Coalition (Jan. 18, 1994), the Hazardous Waste Treatment Council (May 18, 1994), and the Chemical Manufacturers Association (Oct. 14, 1994).

II. Relationship of Today's Proposal to EPA's Waste Minimization National Plan

EPA believes that today's proposed rule will create significant incentives for source reduction and recycling by waste generators that would, in turn, help facilities achieve compliance with the MACT standards. RCRA, as well as the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990 (PPA), encourage pollution prevention at the source, and the Clean Air Act mentions pollution prevention as a specific means of achieving MACT. In §112(d)(2) of the CAA, Congress expressly defined MACT as the "application of measures, processes, methods, systems, or techniques including, but not limited to, measures which reduce the volume of, or eliminate emissions of, such pollutants through process changes, substitution of materials and other modifications."

In addition, in the Hazardous and Solid Waste Amendments of 1984 (HSWA) to RCRA, Congress established a national policy for waste minimization. Section 1003 of RCRA states that, whenever feasible, the generation of hazardous waste is to be reduced or eliminated as expeditiously as possible. Section 8002(r) requires EPA to explore the desirability and feasibility of establishing regulations or other incentives or disincentives for reducing or eliminating the generation of hazardous waste. In 1990, the PPA reinforced these policies by declaring it "to be the national policy of the United States that pollution should be prevented at the source whenever feasible" and, when not feasible, waste should be recycled, treated, or disposed of-in that order of preference.

Although the Agency has devoted significant effort to evaluation and promotion of waste minimization in the past 1, the Hazardous Waste Minimization and Combustion Strategy, first announced in May 1993, recently provided a new impetus to this effort. The Strategy had several components, among which was reducing the amount and toxicity of hazardous waste generated in the United States. Other components of the Strategy included strengthening controls on emissions from hazardous waste combustion units; enhancing public participation in facility permitting; establishing risk assessment policies with respect to facility permitting; and continued emphasis on strong compliance and enforcement.

1 For example, EPA prepared a report to Congress, "Minimization of Hazardous Wastes" (October 1986), that summarized existing waste minimization activities and evaluated options for promoting waste minimization.

EPA held a National Roundtable and four Regional Roundtables throughout the nation in 1993-94 to facilitate a broad dialogue on the spectrum of waste minimization and combustion issues. The major messages from these Roundtables became the building blocks for EPA's further efforts to promote source reduction and recycling and specifically for EPA's Waste Minimization National Plan, released in November 1994.

The Waste Minimization National Plan focuses on the goal of reducing persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic constituents in hazardous waste nationally by 25 percent by the year 2000 and 50 percent by the year 2005. The central themes of the National Plan are: (1) Developing a framework for setting national priorities for the minimization of hazardous waste; (2) promoting multimedia environmental benefits and preventing cross-media transfers; (3) demonstrating a strong preference for source reduction by shifting attention to hazardous waste generators to reduce generation at its source; (4) defining and tracking progress in minimizing the generation of wastes; and (5) involving citizens in waste minimization implementation decisions. The Agency intends to continue its pursuit of hazardous waste minimization under the National Plan and other Agency initiatives in concert with the actions proposed in today's rule.

Of the 3.0 million tons of hazardous waste combusted in 1991, approximately two-thirds of that amount were combusted at on-site facilities (i.e., the same facilities at which the waste was generated). Combustion at an on-site facility therefore presents a situation in which the same facility owners and operators may have some measure of control over generation of wastes at its source and its ultimate disposition. Although close to 400 industries generated wastes destined for combustion in 1991, much of the quantity was concentrated in a few sectors. As a companion to this proposed rule, EPA is focusing its waste minimization efforts on reducing the generation and subsequent release to the environment of the most persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic constituents in hazardous wastes (i.e., metals, halogenated organics).

Analysis of waste minimization potential suggests that generators currently burning wastes may have a number of options for eliminating or reducing these wastes. We believe that roughly 15 percent of all combusted wastes may be amenable to waste minimization. Three waste generating processes appear to have the most potential in terms of tonnage reduction: (1) Solvent and product recovery/distillation procedures, primarily in the organic chemicals industry, (2) product processing wastes, and (3) process waste removal and cleaning. In addition, preliminary analyses of Toxics Release Inventory and hazardous waste stream data indicate that over 3 million pounds of hazardous metals are contained in waste streams being combusted. The top 5 ranking metals (with respect to health risk considering persistence, bioaccumulation, and toxicity) are mercury, cadmium, lead, copper, and selenium. Additional analyses are underway to identify the industry sectors and production processes that are chief sources of these and other high priority hazardous constituents.2

2 USEPA, Office of Solid Waste, "Setting Priorities for Hazardous Waste Minimization", July 1994.

In today's rule, EPA is soliciting comment on two options to promote the use of pollution prevention/waste minimization measures as methods for helping meet MACT standards. These options (regarding feed stream analysis and permitting requirements) are described in Part Five, Section VI, Subsection D of this preamble. EPA is also seeking comment on a proposal to consider, on a case-by-case basis, extending the compliance deadlines for this rule by one year if a facility can show that extra time is needed to implement pollution prevention/waste minimization measures in order for the facility to meet the MACT standards and that implementation cannot be practically achieved within the allotted three-year period after promulgation of this rule (see Part V, Section 1, Subsection C).

PART TWO: DEVICES THAT WOULD BE SUBJECT TO THE PROPOSED EMISSION STANDARDS

I. Hazardous Waste Incinerators

A. Overview

A hazardous waste incinerator is an enclosed, controlled flame combustion device, as defined in 40 CFR 260.10, and is used to treat primarily organic and/or aqueous wastes. These devices may be in situ (fixed), or consist of mobile units (such as those used for site remediation and superfund clean-ups) or may consist of units burning spent or unusable ammunition and/or chemical agents that meet the incinerator definition.

B. Summary of Major Incinerator Designs

The following is a brief description of the typical incinerator designs used in the United States.3

3 For a more detailed description of incineration technology, see "Combustion Emissions Technical Resource Document (CETRED)", USEPA EPA530-R-94-014, May 1994.

1. Rotary Kilns

Rotary kiln systems typically contain two incineration chambers: the rotary kiln and an afterburner. The kiln itself is a cylindrical refractory-lined steel shell 10-20 feet in diameter, with a length-to-diameter ratio of 2 to 10. The shell is supported by steel trundles that ride on rollers, allowing the kiln to rotate around its horizontal axis at a rate of 1-2 revolutions per minute. Wastes are fed directly at one end of the kiln and heated by primary fuels. Waste continues to heat and burn as it travels down the inclined kiln. Combustion air is provided through ports on the face of the kiln. The kiln typically operates at 50-200 percent excess air and temperatures of 1600-1800°F. Flue gas from the kiln is routed to an afterburner operating at 2000-2500°F and 100-200 percent excess air where unburnt components of the kiln flue gas are more completely combusted. Auxiliary fuel and/or pumpable liquid wastes are typically used to maintain the afterburner temperature.

Some rotary kiln incinerators, known as slagging kilns, operate at high enough temperatures such that residual materials leave the kiln in a molten slag form. The molten residue is then water-quenched. Another kiln, an ashing kiln, operates at a lower temperature, producing a residual ash, which leaves as a dry material.

2. Liquid Injection Incinerators

A liquid injection incinerator system consists of an incineration chamber, waste burner and auxiliary fuel system. The combustion chamber is a cylindrical steel shell lined with refractory material and mounted horizontally or vertically. Liquid wastes are atomized as they are fed into the combustion chamber through waste burner nozzles. Typical combustion chamber temperatures are 1300-3000°F and residence times are from 0.5 to 3 seconds.

3. Fluidized Bed Incinerators

A fluidized bed system is essentially a vertical cylinder containing a bed of granular material at the bottom. Combustion air is introduced at the bottom of the cylinder and flows up through the bed material, suspending the granular particles. Waste and auxiliary fuels are injected into the bed, where they mix with combustion air and burn at temperatures from 840-1500°F. Further reaction occurs in the volume above the bed at temperatures up to 1800°F.

4. Fixed Hearth Incinerators

Fixed hearth incinerators typically contain two furnace chambers: a primary and a secondary chamber. Some designs have two or three step hearths on which ash and waste are pushed with rams through the system. A controlled flow 'underfire' combustion air is introduced up through the hearths. The primary chamber operates in "starved air" mode and the temperatures are around 1000°F. The unburnt hydrocarbons reach the secondary chamber where 140-200 percent excess air is supplied and temperatures of 1400-2000°F are achieved for more complete combustion.

C. Number of Incinerator Facilities

Currently, 162 permitted or interim status incinerator facilities, having 190 units, are in operation in the U.S. Another 26 facilities are proposed 4 (i.e., new facilities under construction or permitting). Of the above 162 facilities, 21 facilities are commercial facilities that burn about 700,000 tons of hazardous waste annually. The remaining 141 are on-site or captive facilities and burn about 800,000 tons of waste annually.

4 USEPA "List of hazardous waste incinerators," November 1994.

D. Typical Emission Control Devices for Incinerators

Incinerators are equipped with a wide variety of air pollution control devices (APCDs), which range from no control (for devices burning low ash and low chlorine wastes) to sophisticated state-of-the-art units providing control for several pollutants. Hot flue gases from the incinerators are cooled and cleaned of the air pollutants before they exit the stack. Cooling is mostly done by water quenching, wherein atomized water is sprayed directly into the hot gases. The cooled gases are passed through various pollution control devices to control PM, metals and organic emissions to desired or required levels. Most incinerators use wet APCDs to scrub acid emissions (3 facilities use dry scrubbers). Typical APCDs used include packed towers, spray dryers, or dry scrubbers for acid gas (e.g., HCl, Cl2 control, and venturi-scrubbers, wet or dry electrostatic precipitators (ESPs) or fabric filters for particulate control.

Activated carbon injection for controlling dioxin and mercury is being used at only one incinerator. Newer APC technologies (such as catalytic oxidizers and dioxin/furan inhibitors) have recently emerged, but have not been used on any full scale facilities in the U.S. For detailed description of APCDs, see Appendix A of "Combustion Emissions Technical Resource Document (CETRED)," US EPA Document #EPA530-R-94-014, May 1994.

II. Hazardous Waste-Burning Cement Kilns

A. Overview of Cement Manufacturing

Cement refers to the commodities that are produced by heating mixtures of limestone and other minerals or additives at high temperature in a rotary kiln, followed by cooling, grinding, and finish mixing. This is the manner in which the vast majority of commercially-important cementitious materials are produced in the United States. Cements are used to chemically bind different materials together. The most commonly produced cement type is "Portland" cement, though other standard cement types are also produced on a limited basis (e.g., sulfate-resisting, high-early-strength, masonry, waterproofed). Portland cement is a hydraulic cement, meaning that it sets and hardens by chemical interaction with water. When combined with sand, gravel, water, and other materials, Portland cement forms concrete, one of the most widely used building and construction materials in the world. Cement produced and sold in the U.S. must meet specifications established by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). Each type requires specific additives or changes in the proportions of the raw material mix to make products for specific applications.

B. Summary of Major Design and Operating Features of Cement Kilns

Cement kilns are horizontally inclined rotating cylinders, refractory-brick lined, and internally-fired, that calcine a blend of raw materials containing calcium (typically limestone), silica and alumina (typically clay, shale, slate, and/or sand), and iron (typically steel mill scale or iron ore) to produce Portland cement. Generally, there is a wet process and a dry process for producing cement. In the wet process, the limestone and shale are ground up, wetted and fed into the kiln as a slurry. In the dry process, raw materials are ground dry and fed into the kiln dry. Wet process kilns are typically longer than dry process kilns in order to facilitate water evaporation from the slurried raw material. Wet kilns can be more than 450 feet in length. Dry kilns are more thermally efficient and frequently use preheaters or precalciners to begin the calcining process (i.e., the essential function of driving CO2 from raw materials) before the raw materials are fed into the kiln.

Combustion gases and raw materials move in a counterflow direction, with respect to each other, inside a cement kiln. The kiln is inclined, and raw materials are fed into the upper end (i.e., the "cold" end) while fuels are normally fired into the lower end (i.e., the "hot" end). Combustion gases move up the kiln counter to the flow of raw materials. The raw materials get progressively hotter as they travel down the length of the kiln. The raw materials eventually begin to soften and fuse at temperatures between 2,250 and 2,700°F to form the clinker product. Clinker is then cooled, ground, and mixed with other materials, such as gypsum, to form cement.

Combustion gases leaving the kiln typically contain from 6 to 30 percent of the free solids as dust, which are often recycled to the kiln feed system, though the extent of recycling varies greatly among cement kilns.

Dry kilns with a preheater (PH) or precalciner (PC) often use a by-pass duct to remove from 5 to 30 percent of the kiln off-gases from the main duct. The by-pass gas is passed through a separate air pollution control system to remove particulate matter. Collected by-pass dust is not reintroduced into the kiln system to avoid a build-up of metal salts that can affect product quality.

Some cement kilns burn hazardous waste-derived fuels to replace from 25 to 100 percent of normal fossil fuels (e.g., coal). Most kilns burn liquid waste fuels but several also burn bulk solids and small (e.g., six gallon) containers of viscous or solid hazardous waste fuels. Containers are introduced either at the upper, raw material end of the kiln or at the midpoint of the kiln. EPA has also found that hazardous waste-fired precalciners can still be considered part of the cement kiln and, thus, would be part of an industrial furnace (per the definition in 40 CFR 260.10). See 56 FR at 7184-85 (February 21, 1991). This finding is codified at §266.103(a)(5)(I)(c). This is the only time (and the only rulemaking) in which the Agency found that a device not enumerated in the list of industrial furnaces in §260.10 can be considered part of the industrial furnace when it burns hazardous wastes separate from those burned in the main combustion device.

C. Number of Facilities

The Agency has emissions data from 26 facilities representing 49 cement kilns in the U.S. It should be noted that some facilities no longer burn or process hazardous waste since they were required to certify compliance with the BIF regulations in August 1992.

Of the hazardous waste-burning kilns for which we have emissions data, 14 facilities use a wet process, 5 facilities use a dry process, and the remaining 7 facilities employ either preheaters or preheater/precalciners in the cement manufacturing process.

D. Emissions Control Devices

All hazardous waste-burning cement kilns either use fabric filters (baghouses) or electrostatic precipitators (ESPs) as air pollution control devices. ESPs have traditionally been employed in the cement industry and are currently used at 17 of the facilities. Nine facilities use fabric filters. A detailed description of these and other air pollution control devices is contained in the technical support document. 5

5 USEPA, "Draft Technical Support Document for HWC MACT Standards, Volume I: Description of Source Categories", February 1996.

III. Hazardous Waste-Burning Lightweight Aggregate Kilns

A. Overview of Lightweight Aggregate Kilns (LWAKs)

The term lightweight aggregate refers to a wide variety of raw materials (such as clay, shale, or slate) which after thermal processing can be combined with cement to form concrete products. Lightweight aggregate concrete is produced either for structural purposes or for thermal insulation purposes. A lightweight aggregate plant is typically composed of a quarry, a raw material preparation area, a kiln, a cooler, and a product storage area. The material is taken from the quarry to the raw material preparation area and from there is fed into the rotary kiln.

B. Major Design and Operating Features

A rotary kiln consists of a long steel cylinder, lined internally with refractory bricks, which is capable of rotating about its axis and is inclined at an angle of about 5 degrees to the horizontal. The length of the kiln depends in part upon the composition of the raw material to be processed but is usually 30 to 60 meters. The prepared raw material is fed into the kiln at the higher end, while firing takes place at the lower end. The dry raw material fed into the kiln is initially preheated by hot combustion gases. Once the material is preheated, it passes into a second furnace zone where it melts to a semiplastic state and begins to generate gases which serve as the bloating or expanding agent. In this zone, specific compounds begin to decompose and form gases such as SO2 CO2 SO3 and O2 that eventually trigger the desired bloating action within the material. As temperatures reach their maximum (approximately 2100°F), the semiplastic raw material becomes viscous and entraps the expanding gases. This bloating action produces small, unconnected gas cells, which remain in the material after it cools and solidifies. The product exits the kiln and enters a section of the process where it is cooled with cold air and then conveyed to the discharge.

Kiln operating parameters such as flame temperature, excess air, feed size, material flow, and speed of rotation vary from plant to plant and are determined by the characteristics of the raw material. Maximum temperature in the rotary kiln varies from 2050°F to 2300°F, depending on the type of raw material being processed and its moisture content. Exit temperatures may range from 300°F to 1200°F, again depending on the raw material and on the kiln's internal design. Approximately 80 to 100 percent excess air is forced into the kiln to aid in expanding the raw material.

C. Number of Facilities

EPA has identified 36 lightweight aggregate kiln locations in the United States. Of these, EPA has identified seven facilities that are currently burning hazardous waste in a total of 15 kilns.

D. Air Pollution Control Devices

Lightweight aggregate kilns use one or a combination of air pollution control devices, including fabric filters, venturi scrubbers, spray dryers, cyclones and wet scrubbers. All of the facilities utilize fabric filters as the main type of emissions control, although one facility uses a spray dryer, venturi scrubber and wet scrubber in addition to a fabric filter. For detailed descriptions of these and other air pollution control devices, please see Appendix A of the draft EPA document Combustion Emissions Technical Resource Document (CETRED). 6

6 USEPA, "Draft Combustion Emission Technical Resource Document (CETRED)", EPA 530-R-94-014, May 1994.

PART THREE: DECISION PROCESS FOR SETTING NATIONAL EMISSION STANDARDS FOR HAZARDOUS AIR POLLUTANTS (NESHAPs)

I. Source of Authority for NESHAP Development

The 1990 Amendments to the Clean Air Act significantly revised the requirements for controlling emissions of hazardous air pollutants. EPA is now required to develop a list 7 of categories of major and area sources 8 of the hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) enumerated in section 112 and to develop technology-based performance standards for such sources over specified time periods. See Clean Air Act (the Act or CAA) §§112(c) and 112(d). Section 112 of the Act replaces the previous system of pollutant-by-pollutant health-based regulation that proved ineffective at controlling the high volumes, concentrations, and threats to human health and the environment posed by HAPs in air emissions. See generally S. Rep. No. 228, 101st Cong. 1st Sess. 128-32 (1990).

7 The Agency published an initial list of categories of major and area sources of HAPs on July 16, 1992. See 57 FR 31576.

8 See Part Three, Section III of today's proposal for a discussion of major and area sources. Generally, a major source is a stationary source that emits, or has the potential to emit considering controls, 10 tons per year of a HAP or 25 tons per year of a combination of HAPs. CAA §112(a)(1). An area source is generally a stationary source that is not a major source. Id. §112(a)(2).

Section 112(f) also requires the Agency to report to Congress by the end of 1996 on estimated risk remaining after imposition of technology-based standards and to make recommendations as to legislation to address such risk. CAA §112(f)(1). If Congress does not act on the recommendation, then EPA must address any significant remaining residual risks posed by sources subject to the section 112(d) technology-based standards within 8 years after promulgation of these standards. See §112(f)(2). The Agency is required to impose additional controls if such controls are needed to protect public health with an ample margin of safety, or to prevent adverse environmental effects. Id. In addition, if the technology-based standards for carcinogens do not reduce the lifetime excess cancer risk for the most exposed individual to less than one in a million (1 × 10-6 , then the Agency must promulgate additional standards. See §112(f)(2)(A).

II. Procedures and Criteria for Development of NESHAPs

NESHAPs are developed in order to control HAP emissions from both new and existing sources according to the statutory directives set out in §112. The statute requires a NESHAP to reflect the maximum degree of reduction of HAP emissions that is achievable taking into consideration the cost of achieving the emission reduction, any non-air quality health and environmental impacts, and energy requirements. §112(d)(2). In regulatory parlance, these are often referred to as maximum achievable control technology (or MACT) standards.

The Clean Air Act establishes minimum levels, usually referred to as MACT floors, for the emission standards. Section 112(d)(3) requires that MACT floors be determined as follows: for existing sources in a category or sub-category with 30 or more sources, the MACT floor cannot be less stringent than the "average emission limitation achieved by the best performing 12 percent of the existing sources * * *"; for existing sources in a category or sub-category with less than 30 sources, then the MACT floor cannot be less stringent than the "average emission limitation achieved by the best performing 5 sources * * *"; for new sources, the MACT floor cannot be "less stringent than the emission control that is achieved by the best controlled similar source * * *". See §112(d)(3) (A) and (B).

EPA must, of course, consider in all cases whether to develop standards that are more stringent than the floor ("beyond the floor" standards). To do so, however, EPA must consider the enumerated statutory criteria such as cost, energy, and non-air environmental implications.

Emission reductions may be accomplished through application of measures, processes, methods, systems, or techniques, including, but not limited to: (1) Reducing the volume of, or eliminating emissions of, such pollutants through process changes, substitution of materials, or other modifications; (2) enclosing systems or processes to eliminate emissions; (3) collecting, capturing, or treating such pollutants when released from a process, stack, storage, or fugitive emissions point; (4) design, equipment, work practice, or operational standards (including requirements for operator training or certification); or (5) any combination of the above. See §112(d)(2).

Application of techniques (1) and (2) of the previous paragraph are consistent with the definitions of pollution prevention under the Pollution Prevention Act and the definition of waste minimization under RCRA/HSWA. These terms have particular applicability in the discussion of pollution prevention/waste minimization options presented in the permitting and compliance sections of today's proposal.

To develop a NESHAP, the EPA compiles available information and in some cases collects additional information about the industry, including information on emission source quantities, types and characteristics of HAPs, pollution control technologies, data from HAP emissions tests (e.g., compliance tests, trial burn tests) at controlled and uncontrolled facilities, and information on the costs and other energy and environmental impacts of emission control techniques. EPA uses this information in analyzing and developing possible regulatory approaches. EPA, of course, does not always have or collect the same amount of information per industry, but rather bases the standard on information practically available.

Although NESHAPs are normally structured in terms of numerical emission limits-the preferred means of establishing standards-alternative approaches are sometimes necessary and appropriate. In some cases, for example, physically measuring emissions from a source may be impossible, or at least impractical, because of technological and economic limitations. Section 112(h) authorizes the Administrator to promulgate a design, equipment, work practice, or operational standard, or a combination thereof, in those cases where it is not feasible to prescribe or enforce an emissions standard.

EPA is required to develop emission standards based on performance of maximum achievable control technology for categories or sub-categories of major sources of hazardous air pollutants. §112(d)(1). As explained more fully in the following section, a major source emits, or has the potential to emit considering controls, either 10 tons per year of any hazardous air pollutant or 25 tons or more of any combination of those pollutants. §112(a)(1). EPA also can establish lower thresholds where appropriate. Id. EPA may in addition require sources emitting particularly dangerous hazardous air pollutants (such as particular chlorinated dioxins and furans) to be regulated under the MACT standards for major sources. §112(c)(6).

Area sources are any source which is not a major source. Such sources must be regulated by technology-based standards if they are listed, pursuant to §112(c)(3), based on the Agency's finding that these sources (individually or in the aggregate) present a threat of adverse effects to human health or the environment warranting regulation. After such a determination, the Agency has a further choice as to require technology-based standards based on MACT or on generally achievable control technology (GACT). §112(d)(5).

In this rulemaking, EPA is proceeding pursuant to §112(c)(6) (i.e., imposing MACT controls on area sources), because these hazardous waste combustion units emit a number of the HAPs singled out in that provision, including the enumerated dioxins and furans, mercury, and polycyclic organic matter. (See discussion below.)

III. List of Categories of Major and Area Sources

A. Clean Air Act Requirements

As just discussed, Section 112 of the CAA requires that the EPA promulgate regulations requiring the control of hazardous air pollutants emissions associated with categories or subcategories of major and area sources. These source categories and subcategories are to be listed pursuant to §112(c)(1). EPA published an initial list of 174 categories of such major and area sources in the Federal Register on July 16, 1992 (57 FR 31576).

B. Hazardous Waste Incinerators

"Hazardous waste incinerators" is one of the 174 categories of sources listed. The category consists of commercial and on-site (including captive) incinerating facilities. The listing was based on the Administrator's determination that at least one hazardous waste incinerator may reasonably be anticipated to emit several of the 189 listed HAPs in quantities sufficient to designate them as major sources. EPA used two emission rate values to evaluate the available hazardous waste incinerator emissions data: the maximum emission rate measured during the compliance test, and the average emission rate. The data indicate that approximately 30 percent of the facilities meet the major source criteria when using the maximum emissions rate value. When using the average emissions rate value approximately 15 percent of facilities meet the major source criteria.9 Those facilities meeting the major source criteria do so for HCl and Cl2 emissions, and one facility is also a major source for antimony emissions.

9 For further details see USEPA, "Draft Technical Support Document for HWC MACT Standards, Volume I: Description of Source Categories", February 1996.

It should be noted that a major source and boundary for considering whether a source is a major includes all potential emission points of HAPs at that contiguous facility, including storage tanks, equipment leaks, and other hazardous waste handling facilities. The above calculations for incinerators on whether a source is a major source under §112 do not reflect these potential emission points.

Notwithstanding the fact that most HW incinerators are not likely to meet the HAP emission thresholds for major sources, the Agency is proposing to subject all HWCs to regulation under MACT as major sources, under the authority of §112(c)(6). See Section IV below.

C. Cement Kilns

Another of the 174 categories of major and area sources of HAPs is Portland Cement Manufacturing (cement kilns). In evaluating the emissions data for the hazardous waste-burning cement kilns, 85 percent of the cement kilns were determined to meet the major source criteria when using the maximum emission rate value. Using the average emission rate value, just over 80 percent of the hazardous waste-burning cement kilns meet the major source criteria.10 Those facilities meeting the major source criteria do so for HCl and Cl2 emissions, and one facility is also a major source for organic emissions. It should be noted that the calculation on whether a cement kiln is a major source did not include potential emission points of HAPs at that contiguous facility.

10 Ibid.

Notwithstanding the fact that some hazardous waste-burning cement kilns may not meet the definition of major source, the Agency is proposing to subject all HWCs to regulation under MACT, as major sources, under the authority of §112(c)(6). See Section IV below.

D. Lightweight Aggregate Kilns

Section 112(c)(5) authorizes EPA to amend the source category list at any time to add categories or subcategories that meet the listing criteria. EPA is proposing to exercise that authority by adding HW-burning lightweight aggregate kilns to the list of source categories.

In analyzing the emissions data, EPA found that all hazardous waste-burning LWAKs met the major source criteria for two HAPs, HCl and Cl2 using either the average or maximum emission rate value. 11 It should be noted that the calculation on whether a LWAK is a major source did not include potential emission points of HAPs at that contiguous facility. EPA is therefore proposing today the addition of hazardous waste-burning LWAKs as a source category in accordance with section 112(c)(5) of the Act. In addition, as discussed below, even if a LWAK would otherwise be an area source, EPA is proposing to subject it to the same NESHAPS as major LWAK sources.

11 Ibid.

IV. Proposal To Subject Area Sources to the NESHAPs Under Authority of Section 112(c)(6)

EPA is today proposing to subject all hazardous waste incinerators, hazardous waste-burning cement kilns, and hazardous waste-burning lightweight aggregate kilns (i.e., both area and major sources) to regulation as major sources pursuant to CAA §112(c)(6). That provision states that, by November 15, 2000, EPA must list and promulgate §112 (d)(2) or (d)(4) standards (i.e., standards reflecting MACT) for categories (and subcategories) of sources emitting specific pollutants, including the following HAPs emitted by HWCs: polycyclic organic matter, mercury, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzofuran, and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. (Although the Agency has not prepared the list, it is the Agency's intention to include hazardous waste combustors.) EPA must assure that sources accounting for not less than 90 percent of the aggregate emissions of each enumerated pollutant are subject to MACT standards.

The chief practical effect of invoking §112(c)(6) for this rulemaking is to subject area sources that emit 112(c)(6) pollutants to the same MACT standards as major sources, rather than to the potentially less stringent 112(d)(5) or "GACT" ("generally achievable control technology") standards.12 Today's proposal constitutes one of many EPA actions to assure that sources accounting for at least 90 percent of emissions of §112(c)(6) pollutants are subject to MACT standards.

12 EPA also solicits comment on an alternative reading of §112(c)(6), whereby the provision would require MACT control for the enumerated pollutants but not necessarily for other HAPs emitted by the source, which HAPs are not enumerated in §112(c)(6).

Although §112(c)(6) requires the Agency to regulate source categories that emit not less than 90 percent of the aggregate emissions of the high priority HAPs, the Agency will use its discretion to avoid regulating area source categories with trivial aggregate emissions of specific §112(c)(6) HAPs. However, as an example of the emissions that are possible from the HWC source categories, it is estimated that HWCs presently emit in aggregate 11.1 tons of mercury per year. Of this quantity, 4.6 tons per year can be attributed to hazardous waste incinerators and 6.5 tons per year to hazardous waste-burning cement and lightweight aggregate kilns. Also, it is estimated that HWCs preiently emit in aggregate 122 pounds of dioxins/furans (or 2.15 pounds TEQ) per year. Of this quantity, 9 pounds (or 0.2 pounds TEQ) per year can be attributed to hazardous waste incinerators and 113 pounds (or 1.95 pounds TEQ) per year to hazardous waste-burning cement and lightweight aggregate kilns. To show an example of how today's proposal constitutes an action to assure that sources accounting for at least 90 percent of emissions of §112(c)(6) pollutants are subject to MACT standards, the document Estimating Exposure to Dioxin-Like Compounds, Vol. II: Properties, Sources, Occurrence and Background Exposures (EPA, 1994) estimates (on p. 29) that national emissions of dioxins and furans (D/F) total 4.18 pounds TEQ per year. Based on this estimation, HWCs account for 51 percent of the annual national emissions of D/F. (Consequently, EPA expects these source categories to be included in the list of sources to be controlled to achieve the requisite 90 percent reduction in aggregate emissions of section 112(c)(6) pollutants.)

Congress singled out the HAPs enumerated in §112(c)(6) as being of "specific concern" not just because of their toxicity but because of their propensity to cause substantial harm to human health and the environment via indirect exposure pathways (i.e., from the air through other media, such as water, soil, food uptake, etc.). S. Rep. No. 228, 101st Cong. 1st Sess., pp. 155, 166. These pollutants have exhibited special potential to bioaccumulate, causing pervasive environmental harm in biota (and, ultimately, human health risks). Id. Indeed, as discussed later, the data appear to show that much of the human health risk from emissions of these HAPs from HWCs comes from these indirect exposure pathways. Id. at p. 166. Congress' express intention was to assure that sources emitting significant quantities of §112(c)(6) pollutants received a stricter level of control. Id.

V. Selection of MACT Floor for Existing Sources

The starting point in developing MACT standards is determining floor levels, i.e. the minimum (least stringent) level at which the standard can be set.

All of the hazardous waste combustion units subject to this proposed rule are already subject to RCRA regulation under 40 CFR Parts 264, 265, or 266. As a result, the Agency has a substantial amount of data reflecting performance of these devices. These data consist largely of trial burn data for hazardous waste incinerators and data from certifications of compliance for hazardous waste-burning cement kilns and LWAKs obtained pursuant to 266.103(c). These data consist of at least three runs for any given test condition.

In using these "short term" test data to establish a MACT floor, the Agency has developed an approach that ensures the standards are achievable, i.e. reflect the performance over time of properly designed and operated air pollution control devices (or operating practices) taking into account intrinsic operating variability.

In addition, the Agency notes that the floor calculations were performed on individual HAPs or, in the case of metals, in two groups of HAPs that behave similarly (i.e., separate floor levels for each hazardous air pollutant or group of metal pollutants). However, for HAPs that are controlled by the same type of air pollution control device (APCD), EPA has ensured that all HAP floors are simultaneously achievable by identifying the APCD and APCD treatment train that can be used to meet all floor levels. The ultimate floor levels thus derived can be achieved using the identified technology. This approach is consistent with methods used by EPA in other rules to calculate MACT requirements where the HAP species present must be treated by a treatment train. See, e.g., MACT Rules for Secondary Lead Smelters. 60 FR 32589 (June 23, 1995).

The Agency is not, however, treating hazardous waste-burning incinerators, cement kilns, and LWAKs as a single source category for purposes of developing the MACT floor (or for any other purpose). The Agency's initial view is that there are technical differences in performance for particular HAPs among the three source categories, and therefore that the technology-based floors must reflect these operating differences.

A. Proposed Approach: Combined Technology-Statistical Approach

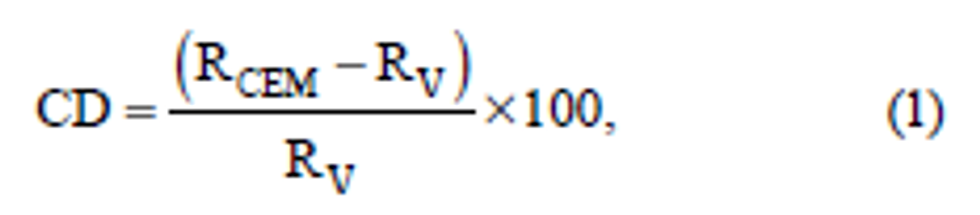

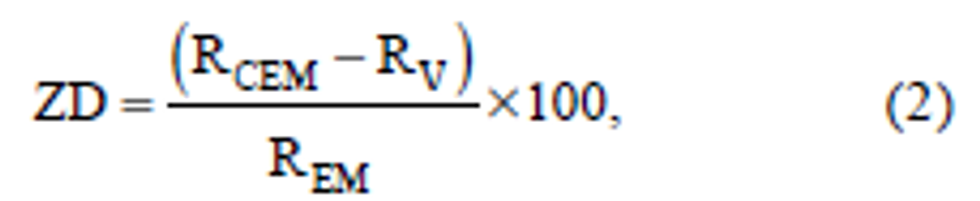

This analysis first identified the best performing control technology(ies) for each source category (i.e., incinerators, cement kilns, and lightweight aggregate kilns) and each HAP of concern by arraying from lowest to highest all the particular HAP emissions data from existing units within the source category by test condition averages. These technologies comprise MACT floor. In cases where a source had emissions data for a HAP from several different test conditions of a compliance test, the Agency arrayed each test condition separately. The Agency then identified the emission control technology or technologies (and normalized feedrate of metals and chlorine in hazardous waste) used by sources with emissions levels at or below the level emitted by the median of the best performing 12 percent of sources. The sources are termed "the best performing 6 percent" of the sources, or "MACT pool", and the controls they use comprise MACT floor.

The next step was to identify an emissions level that MACT floor control could achieve. Thus, emissions data from all sources (in the source category) that use MACT floor control were arrayed in ascending order by average emissions. [This is referred to as the "expanded MACT pool" or "expanded universe".] The Agency evaluated the control technologies used by the additional sources within the "expanded universe" as available data allowed to ensure that they were in fact equivalent in design to MACT floor. The Agency then selected the test condition in the expanded MACT pool with the highest mean emissions to identify the emission level that MACT floor could achieve.

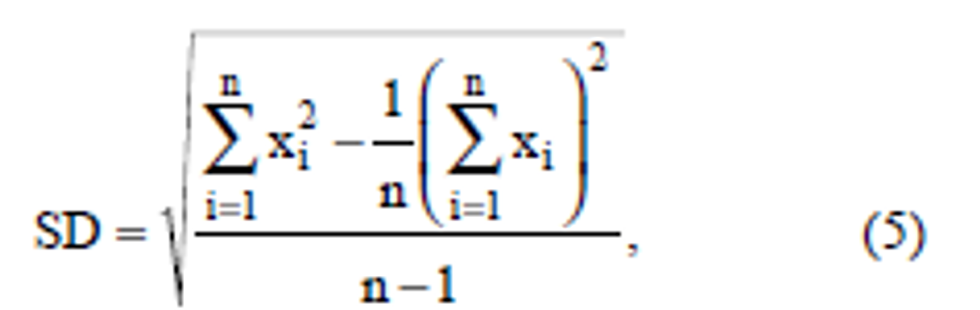

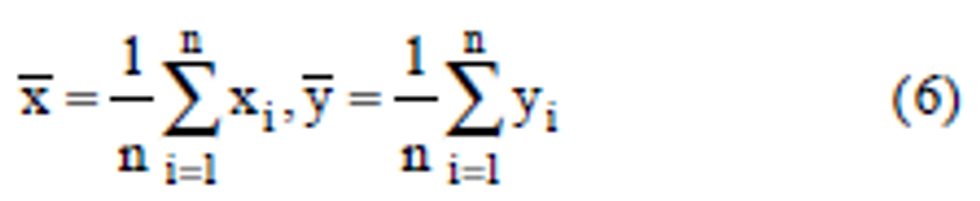

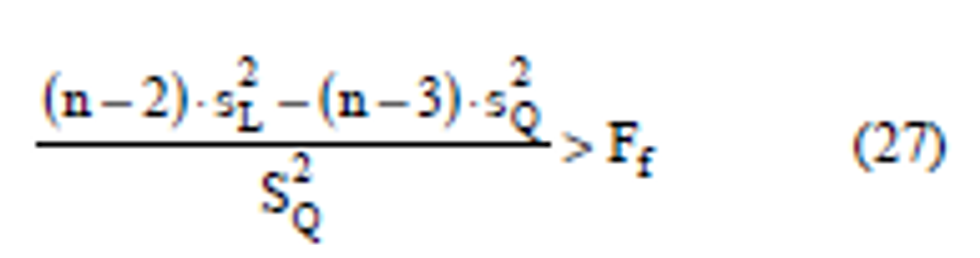

Because the emissions database was comprised of "short-term" test data, the Agency used a statistical approach to identify an emission level that MACT floor could achieve routinely. The Agency then identified the test condition in the expanded MACT pool with the highest mean emissions to statistically calculate a "design level" and a floor standard. The design level was calculated as the log mean of the emissions for the test condition. The standard was calculated as a level that a source (that is designed and operated to routinely meet the design level) could meet 99 percent of the time if it has the average within-test-condition emissions variability of the expanded MACT pool. Although the Agency evaluated 90th and 95th percentile limits, the 99th percentile limit was chosen to: (1) More accurately reflect the variability that could be present in emissions data, and (2) appropriately characterize this variability in light of the consequence of failing to achieve the emissions standards. Additional information on how MACT floor levels were identified is provided in the "Draft Technical Support Document for HWC MACT Standards, Volume III: Selection of Proposed MACT Standards and Technologies".

In accounting for operating variability, the Agency solicits comment on whether it may have overcompensated so that the identified floor levels are unduly lenient. The test data on which the proposal is based to some extent reflect worst-case performance conditions because RCRA sources try to obtain maximum operating flexibility by conducting test burns at extreme operating conditions. For example, many sources spike wastes with excess metals and chlorine during compliance testing. In addition, sources operate their emissions control devices under low efficiency conditions (while still meeting emission standards) to ensure lenient operating limits. It thus may be that the Agency's emissions database is so inflated that separate consideration of emissions variability may not be warranted. A floor level could be the highest mean of the test conditions in the expanded MACT pool.

The Agency emphasizes that it would be preferable, for purposes of setting these MACT standards, to have operational and emissions data that better reflect long-term, more routine day-to-day facility operations from all of the source categories. We believe that this type of data would enable the MACT process to articulate a set of HAP standards that would not create some of the issues raised in subsequent sections of this preamble (such as the most appropriate resolution of a variability factor, the optimum approach for considering the contribution of cement and lightweight aggregate kiln raw material feed to HAP emissions, and better identification among sources that are now in an expanded MACT pool but which, with better data, would be determined not to be employing the identified floor controls). As noted in these subsequent sections, the Agency urges commenters to submit these types of data.

B. Another Approach Considered but not Used

Although the Agency believes the proposed approach reflects a reasonable interpretation of the statute, there are other possible interpretations. One of these interpretations, termed the "12 percent approach", was raised and, in fact, evaluated during the process already outlined. This approach is presented here, along with the results of the process in Part Four, Section VIII, for public inspection.

This "12 percent approach" was evaluated in a like manner to the Agency's preferred approach just described. Again, the best performing control technology(ies) for each source category and each HAP were identified by arraying the data by test condition averages. However, the Agency identified the technology or technologies used by the best performing 12 percent of the sources. After arraying emissions data from all facilities in the source category that use the identified MACT floor technology(ies) (i.e., the expanded MACT pool), the Agency selected an emissions floor level based on the statistical average of the 12 percent MACT pool, to which was added the average within-test condition variability within the expanded MACT pool. The emissions floor was then calculated at a level that a source with average emissions variability would be expected to achieve 99 percent of the time. The approach was not proposed because it could not be demonstrated that sources within the expanded MACT pool using MACT floor controls could achieve the floor levels. Again, the details of the statistical methods employed are presented in the "Draft Technical Support Document for HWC MACT Standards, Volume III: Selection of Proposed MACT Standards and Technologies".

C. Identifying Floors as Proposed in CETRED

The discussion in the Draft Combustion Emissions Technical Resource Document (CETRED) (U.S. EPA, EPA530-R-94-014, May 1994) presented one methodology for establishing particulate matter (PM) and dioxin/furan (D/F) technology-based emission levels for hazardous waste combustors (HWCs). The document presented a procedure for establishing numerical levels which took into account the natural variability that was present in the Agency's PM and D/F emissions data. EPA received numerous comments on the document.

The approaches outlined in CETRED were an initial and preliminary attempt to apply the process by which the NESHAPs are to be established for the existing types of hazardous waste combustors. The approaches in CETRED focused solely on the performance of MACT and how to establish the "floor" emission level under the MACT process.

In CETRED, determination of the MACT floor involved: (1) screening unrepresentative data; (2) ranking all HWC sources based on the data average, considering variability; (3) identifying the top 12 percent of sources as the MACT pool; and (4) statistically evaluating the MACT pool to set the MACT floor. These elements and considerations are described in further detail in CETRED and the "Draft Technical Support Document for HWC MACT Standards, Volume III: Selection of Proposed MACT Standards and Technologies". The Agency specifically indicated the preliminary nature of the CETRED approaches and, in light of further deliberations and comments received, has considered and adopted other approaches for this proposal. The comments received are found in the docket.

In considering the use of a purely statistical approach to setting MACT floors, the Agency recognized that whether sources could actually achieve a statistically-derived MACT floor level on a regular basis was significant in determining whether a purely statistical approach could be appropriate or not. The Agency encountered difficulties in identifying an appropriate purely statistical model for the combined source category (HW incinerators, HW-burning cement kilns, and HW-burning lightweight aggregate kilns) emissions database. Consequently, the Agency abandoned a purely statistical approach and examined an approach-referred to here as the "technology approach"-that used demonstrated technological capabilities as a key factor in selecting MACT floor levels.

D. Establishing Floors One HAP or HAP Group at a Time

EPA believes it is permissible to establish MACT floors separately for individual HAPs or group of HAPs that behave the same from a technical standpoint (i.e., based on separate MACT pools and floor controls), provided the various MACT floors are simultaneously achievable. As set out below, Congress has not spoken to this precise issue. An interpretation that allows this approach is consistent with statutory goals and policies, as well as established EPA practice in developing MACT standards.

As described earlier, Congress specified in section 112(d)(3) the minimum level of emission reduction that could satisfy the requirement to adopt MACT. For new sources, this floor level is to be "the emission control that is achieved in practice by the best controlled similar source". For existing sources, the floor level is to be "the average emission limitation achieved by the best performing 12 percent of the existing sources" for categories and subcategories with 30 or more sources, or "the average emission limitation achieved by the best performing 5 sources" for categories and subcategories with fewer than 30 sources. An "emission limitation" is "a requirement * * * which limits the quantity, rate, or concentration of emissions of air pollutants" (section 302 (k)) (although the extent, if any, the section 302 definitions need to apply to the terms used in section 112 is not clear).

This language does not expressly address whether floor levels can be established HAP-by-HAP. The existing source MACT floor achieved by the average of the best performing 12 percent can reasonably be read as referring to the source as a whole or performance as to a particular HAP. The statutory definition of "emission limitation" (assuming it applies) likewise is ambiguous, since "requirements limiting quantity, rate, or concentration of pollutants" could apply to particular HAPs or all HAPs. The reference in the new source MACT floor to "emission control achieved by the best controlled similar source" can mean emission control as to a particular HAP or achieved by a source as a whole.

Here, Congress has not spoken to the precise question at issue, and the Agency's interpretation effectuates statutory goals and policies in a reasonable manner. See Chevron v. NRDC, 467 U.S. 837 (1984) (indicating that such interpretations must be upheld). The central purpose of the amended air toxics provisions was to apply strict technology-based emission controls on HAPs. See, e.g., H. Rep. No. 952, 101st Cong. 2d sess. 338. The floor's specific purpose was to assure that consideration of economic and other impacts not be used to "gut the standards". While costs are by no means irrelevant, they should by no means be the determining factors. There needs to be a minimum degree of control in relation to the control technologies that have already been attained by the best existing sources. Legislative History of the Clean Air Act Vol. II at 2897 (statement of Rep. Collins).

Furthermore, an alternative interpretation would tend to result in least common denominator floors where multiple HAPs are emitted, whereby floors would no longer be reflecting performance of the best performing sources. For example, if the best performing 12 percent of facilities for HAP metals did not control organics as well as a different 12 percent of facilities, the floor for organics and metals would end up not reflecting best performance. Indeed, under this reading, the floor would be no control, because no plant is controlling both types of HAPs.

EPA is convinced that this result is not compelled by the statutory text, and does not effectuate the evident statutory purpose of having floor levels reflect performance of an average of a group of best-performing sources. Conversely, using a HAP-by-HAP approach (or an approach that groups HAPs based on technical factors) to identify separate floors for metals and organics in this example promotes the stated purpose of the floor to provide a minimum level of control reflecting what best performing existing sources have already demonstrated an ability to do.

EPA notes, however, that if optimized performance for different HAPs is not technologically possible due to mutually inconsistent control technologies (for example, metals performance decreases if organics reduction is optimized), then this would have to be taken into account in establishing a floor (or floors). (Optimized controls for both types of HAPS would not be MACT in any case, since the standards would not be mutually achievable.) The Senate Report indicates that in such a circumstance, EPA is to optimize the part of the standard providing the most environmental protection. S. Rep. No. 228, 101st Cong. 1st sess. 168. It should be emphasized, however, that "the fact that no plant has been shown to be able to meet all of the limitations does not demonstrate that all the limitations are not achievable". Chemical Manufacturers Association v. EPA, 885 F. 2d at 264 (upholding technology-based standards based on best performance for each pollutant by different plants, where at least one plant met each of the limitations but no single plant met all of them).

All available data for HWCs indicate that there is no technical problem achieving the floor levels for each HAP or HAP metal group simultaneously, using the MACT floor technology. In the case of metals and PM, the characteristics of the MACT floor technology associated with the hardest-to-meet floor (e.g., the fabric filter with lowest air-to-cloth ratio) would define the MACT floor technology for purposes of determining achievability of floors and for purposes of costing out the impact of the standards. Existing data show that approximately 9 percent of existing hazardous waste incinerators, approximately 8 percent of hazardous waste-burning cement kilns, and approximately 25 percent of hazardous waste-burning LWAKs are already achieving the proposed floor standards for all HAPs.

Finally, EPA notes that the HAP-by-HAP or HAP group approach to establishing MACT floor levels is not unique to this rule. For example, the Agency has adopted it for the NESHAP for the secondary lead source category (60 FR 32589 (June 23, 1995)) and proposed the same approach for municipal waste combustors (59 FR 48198 (September 20, 1994)).

As discussed above, EPA has the authority to establish MACT floors on a HAP group by HAP group basis and has done so in this case. In doing so, EPA will ensure that such floors, taken as a whole, are reasonably achievable for facilities subject to the MACT standards.

VI. Selection of Beyond-the-Floor Levels for Existing Sources

As discussed in Section V above, the MACT floor defines the minimum level of emission control for existing sources, regardless of cost or other considerations. The process of considering emissions levels more stringent than the MACT floor for existing sources is called a "beyond-the-floor" (BTF) analysis and involves consideration of certain additional factors, including cost, any non-air quality health and environmental impacts and energy requirements, technologies currently in use within these industry sectors, and also other more efficient and appropriate technologies that have been demonstrated and are available on the market (e.g., carbon bed for dioxin/furan control).

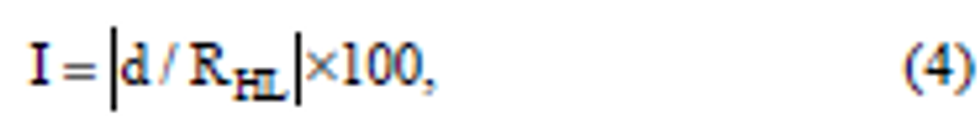

Because there are virtually unlimited BTF emissions levels that the Agency could consider, the Agency used several criteria in this proposal to identify when to examine a particular beyond-the-floor emissions level in detail, and also whether to propose a MACT standard based on the beyond-the-floor emissions levels for existing sources.