['Wage and Hour']

['Minimum Wage']

05/17/2022

...

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

Office of the Secretary

29 CFR Part 10

RIN 1235-AA10

Establishing a Minimum Wage for Contractors

AGENCY: Wage and Hour Division, Department of Labor.

ACTION: Final rule.

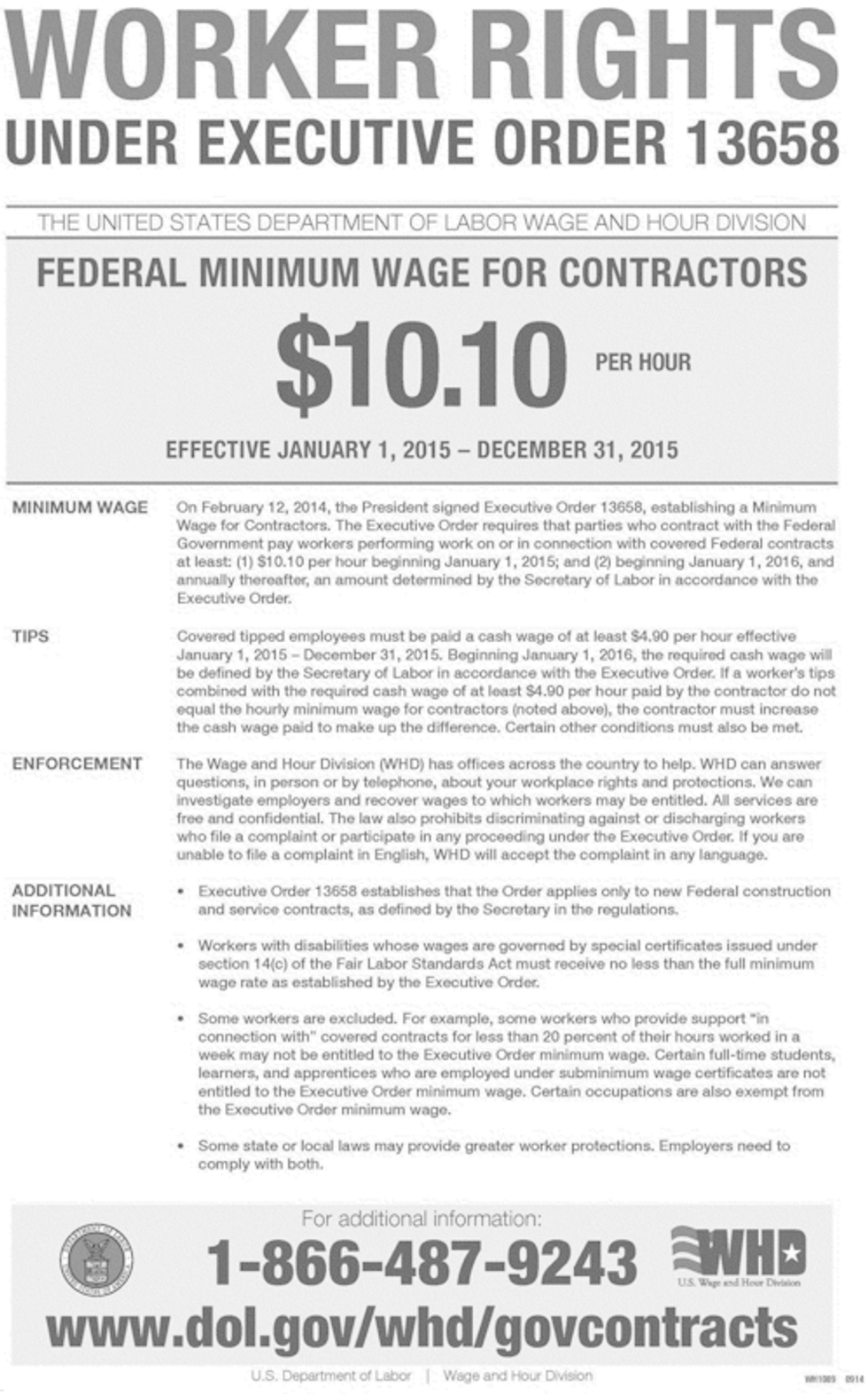

SUMMARY: In this final rule, the Department of Labor issues final regulations to implement Executive Order 13658, Establishing a Minimum Wage for Contractors, which was signed by President Barack Obama on February 12, 2014. Executive Order 13658 states that the Federal Government's procurement interests in economy and efficiency are promoted when the Federal Government contracts with sources that adequately compensate their workers. The Executive Order therefore seeks to raise the hourly minimum wage paid by those contractors to workers performing work on covered Federal contracts to: $10.10 per hour, beginning January 1, 2015; and beginning January 1, 2016, and annually thereafter, an amount determined by the Secretary of Labor. The Executive Order directs the Secretary to issue regulations by October 1, 2014, to the extent permitted by law and consistent with the requirements of the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act, to implement the Order's requirements. This final rule therefore establishes standards and procedures for implementing and enforcing the minimum wage protections of Executive Order 13658. As required by the Order, the final rule incorporates to the extent practicable existing definitions, procedures, remedies, and enforcement processes under the Fair Labor Standards Act, the Service Contract Act, and the Davis-Bacon Act.

DATES: Effective date: This final rule is effective on December 8, 2014.

Applicability date: For procurement contracts subject to the Federal Acquisition Regulation and Executive Order 13658, this final rule is applicable beginning on the effective date of regulations revising 48 CFR parts 22 and 52 issued by the Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Timothy Helm, Chief, Branch of Government Contracts Enforcement, Office of Government Contracts, Wage and Hour Division, U.S. Department of Labor, Room S-3006, 200 Constitution Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20210; telephone: (202) 693-0064 (this is not a toll-free number). Copies of this final rule may be obtained in alternative formats (Large Print, Braille, Audio Tape or Disc), upon request, by calling (202) 693-0675 (this is not a toll-free number). TTY/TDD callers may dial toll-free 1-877-889-5627 to obtain information or request materials in alternative formats.

Questions of interpretation and/or enforcement of the agency's regulations may be directed to the nearest Wage and Hour Division (WHD) district office. Locate the nearest office by calling the WHD's toll-free help line at (866) 4US-WAGE ((866) 487-9243) between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. in your local time zone, or log onto the WHD's Web site for a nationwide listing of WHD district and area offices at http://www.dol.gov/whd/america2.htm.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

I. Executive Order 13658 Requirements and Background

On February 12, 2014, President Barack Obama signed Executive Order 13658, Establishing a Minimum Wage for Contractors (the Executive Order or the Order). 79 FR 9851. The Executive Order states that the Federal Government's procurement interests in economy and efficiency are promoted when the Federal Government contracts with sources that adequately compensate their workers. Id. The Order therefore “seeks to increase efficiency and cost savings in the work performed by parties who contract with the Federal Government” by raising the hourly minimum wage paid by those contractors to workers performing work on covered Federal contracts to (i) $10.10 per hour, beginning January 1, 2015; and (ii) beginning January 1, 2016, and annually thereafter, an amount determined by the Secretary of Labor (Secretary) in accordance with the Executive Order. Id.

Section 1 of Executive Order 13658 sets forth a general position of the Federal Government that increasing the hourly minimum wage paid by Federal contractors to $10.10 will “increase efficiency and cost savings” for the Federal Government. 79 FR 9851. The Order states that raising the pay of low-wage workers increases their morale and productivity and the quality of their work, lowers turnover and its accompanying costs, and reduces supervisory costs. Id. The Order further states that these savings and quality improvements will lead to improved economy and efficiency in Government procurement. Id.

Section 2 of Executive Order 13658 therefore establishes a minimum wage for Federal contractors and subcontractors. 79 FR 9851. The Order provides that executive departments and agencies (agencies) shall, to the extent permitted by law, ensure that new contracts, contract-like instruments, and solicitations (collectively referred to as “contracts”), as described in section 7 of the Order, include a clause, which the contractor and any subcontractors shall incorporate into lower-tier subcontracts, specifying, as a condition of payment, that the minimum wage to be paid to workers, including workers whose wages are calculated pursuant to special certificates issued under 29 U.S.C. 214(c),1 in the performance of the contract or any subcontract thereunder, shall be at least: (i) $10.10 per hour beginning January 1, 2015; and (ii) beginning January 1, 2016, and annually thereafter, an amount determined by the Secretary in accordance with the Executive Order. 79 FR 9851. As required by the Order, the minimum wage amount determined by the Secretary pursuant to this section shall be published by the Secretary at least 90 days before such new minimum wage is to take effect and shall be: (A) Not less than the amount in effect on the date of such determination; (B) increased from such amount by the annual percentage increase, if any, in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (United States city average, all items, not seasonally adjusted) (CPI-W), or its successor publication, as determined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics; and (C) rounded to the nearest multiple of $0.05. Id.

129 U.S.C. 214(c) authorizes employers, after receiving a certificate from the WHD, to pay subminimum wages to workers whose earning or productive capacity is impaired by a physical or mental disability for the work to be performed.

Section 2 of the Executive Order further explains that, in calculating the annual percentage increase in the CPI for purposes of this section, the Secretary shall compare such CPI for the most recent month, quarter, or year available (as selected by the Secretary prior to the first year for which a minimum wage determined by the Secretary is in effect pursuant to this section) with the CPI for the same month in the preceding year, the same quarter in the preceding year, or the preceding year, respectively. 79 FR 9851. Pursuant to this section, nothing in the Order excuses noncompliance with any applicable Federal or State prevailing wage law or any applicable law or municipal ordinance establishing a minimum wage higher than the minimum wage established under the Order. Id.

Section 3 of Executive Order 13658 explains the application of the Order to tipped workers. 79 FR 9851-52. It provides that for workers covered by section 2 of the Order who are tipped employees pursuant to 29 U.S.C. 203(t), the hourly cash wage that must be paid by an employer to such employees shall be at least: (i) $4.90 an hour, beginning on January 1, 2015; (ii) for each succeeding 1-year period until the hourly cash wage under this section equals 70 percent of the wage in effect under section 2 of the Order for such period, an hourly cash wage equal to the amount determined under section 3 of the Order for the preceding year, increased by the lesser of: (A) $0.95; or (B) the amount necessary for the hourly cash wage under section 3 to equal 70 percent of the wage under section 2 of the Order; and (iii) for each subsequent year, 70 percent of the wage in effect under section 2 for such year rounded to the nearest multiple of $0.05. 79 FR 9851-52. Where workers do not receive a sufficient additional amount on account of tips, when combined with the hourly cash wage paid by the employer, such that their wages are equal to the minimum wage under section 2 of the Order, section 3 requires that the cash wage paid by the employer be increased such that their wages equal the minimum wage under section 2 of the Order. 79 FR 9852. Consistent with applicable law, if the wage required to be paid under the Service Contract Act (SCA), 41 U.S.C. 6701 et seq., or any other applicable law or regulation is higher than the wage required by section 2 of the Order, the employer must pay additional cash wages sufficient to meet the highest wage required to be paid. Id.

Section 4 of Executive Order 13658 provides that the Secretary shall issue regulations by October 1, 2014, to the extent permitted by law and consistent with the requirements of the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act, to implement the requirements of the Order, including providing exclusions from the requirements set forth in the Order where appropriate. 79 FR 9852. It also requires that, to the extent permitted by law, within 60 days of the Secretary issuing such regulations, the Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council (FARC) shall issue regulations in the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) to provide for inclusion of the contract clause in Federal procurement solicitations and contracts subject to the Executive Order. Id. Additionally, this section states that within 60 days of the Secretary issuing regulations pursuant to the Order, agencies must take steps, to the extent permitted by law, to exercise any applicable authority to ensure that contracts for concessions and contracts entered into with the Federal Government in connection with Federal property or lands and related to offering services for Federal employees, their dependents, or the general public, entered into after January 1, 2015, consistent with the effective date of such agency action, comply with the requirements set forth in sections 2 and 3 of the Order. Id. The Order further specifies that any regulations issued pursuant to this section should, to the extent practicable and consistent with section 8 of the Order, incorporate existing definitions, procedures, remedies, and enforcement processes under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), 29 U.S.C. 201 et seq.; the SCA; and the Davis-Bacon Act (DBA), 40 U.S.C. 3141 et seq. 79 FR 9852.

Section 5 of Executive Order 13658 grants authority to the Secretary to investigate potential violations of and obtain compliance with the Order. 79 FR 9852. It also explains that Executive Order 13658 does not create any rights under the Contract Disputes Act and that disputes regarding whether a contractor has paid the wages prescribed by the Order, to the extent permitted by law, shall be disposed of only as provided by the Secretary in regulations issued pursuant to the Order. Id.

Section 6 of Executive Order 13658 establishes that if any provision of the Order or the application of such provision to any person or circumstance is held to be invalid, the remainder of the Order and the application shall not be affected. 79 FR 9852.

Section 7 of the Executive Order provides that nothing in the Order shall be construed to impair or otherwise affect the authority granted by law to an agency or the head thereof; or the functions of the Director of the Office of Management and Budget relating to budgetary, administrative, or legislative proposals. 79 FR 9852-53. It also states that the Order is to be implemented consistent with applicable law and subject to the availability of appropriations. 79 FR 9853. The Order explains that it is not intended to, and does not, create any right or benefit, substantive or procedural, enforceable at law or in equity by any party against the United States, its departments, agencies, or entities, its officers, employees, or agents, or any other person. Id.

Section 7 of Executive Order 13658 further establishes that the Order shall apply only to a new contract, as defined by the Secretary in the regulations issued pursuant to section 4 of the Order, if: (i)(A) It is a procurement contract for services or construction; (B) it is a contract for services covered by the SCA; (C) it is a contract for concessions, including any concessions contract excluded by Department of Labor (the Department) regulations at29 CFR 4.133(b); or (D) it is a contract entered into with the Federal Government in connection with Federal property or lands and related to offering services for Federal employees, their dependents, or the general public; and (ii) the wages of workers under such contract are governed by the FLSA, the SCA, or the DBA. 79 FR 9853. Section 7 of the Order also states that, for contracts covered by the SCA or the DBA, the Order shall apply only to contracts at the thresholds specified in those statutes.2 Id. Additionally, for procurement contracts where workers' wages are governed by the FLSA, the Order specifies that it shall apply only to contracts that exceed the micro-purchase threshold, as defined in 41 U.S.C. 1902(a),3 unless expressly made subject to the Order pursuant to regulations or actions taken under section 4 of the Order. 79 FR 9853. The Executive Order specifies that it shall not apply to grants; contracts and agreements with and grants to Indian Tribes under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (Pub. L. 93-638), as amended; or any contracts expressly excluded by the regulations issued pursuant to section 4(a) of the Order. 79 FR 9853. The Order also strongly encourages independent agencies to comply with its requirements. Id.

2The prevailing wage requirements of the SCA apply to covered prime contracts in excess of $2,500. See 41 U.S.C. 6702(a)(2) (recodifying 41 U.S.C. 351(a)). The DBA applies to covered prime contracts that exceed $2,000. See 40 U.S.C. 3142(a). There is no value threshold requirement for subcontracts awarded under such prime contracts.

341 U.S.C. 1902(a) defines the micro-purchase threshold as $3,000.

Section 8 of Executive Order 13658 provides that the Order is effective immediately and shall apply to covered contracts where the solicitation for such contract has been issued on or after: (i) January 1, 2015, consistent with the effective date for the action taken by the FARC pursuant to section 4(a) of the Order; or (ii) for contracts where an agency action is taken pursuant to section 4(b) of the Order, January 1, 2015, consistent with the effective date for such action. 79 FR 9853. It also specifies that the Order shall not apply to contracts entered into pursuant to solicitations issued on or before the effective date for the relevant action taken pursuant to section 4 of the Order. Id. Finally, section 8 states that, for all new contracts negotiated between the date of the Order and the effective dates set forth in this section, agencies are strongly encouraged to take all steps that are reasonable and legally permissible to ensure that individuals working pursuant to those contracts are paid an hourly wage of at least $10.10 (as set forth under sections 2 and 3 of the Order) as of the effective dates set forth in this section. 79 FR 9854.

II. Discussion of Final Rule

A. Legal Authority

The President issued Executive Order 13658 pursuant to his authority under “the Constitution and the laws of the United States,” expressly including the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act (Procurement Act), 40 U.S.C. 101 et seq. 79 FR 9851. The Procurement Act authorizes the President to “prescribe policies and directives that the President considers necessary to carry out” the statutory purposes of ensuring “economical and efficient” government procurement and administration of government property. 40 U.S.C. 101, 121(a). Executive Order 13658 delegates to the Secretary the authority to issue regulations to “implement the requirements of this order.” 79 FR 9852. The Secretary has delegated his authority to promulgate these regulations to the Administrator of the WHD. Secretary's Order 05-2010 (Sept. 2, 2010), 75 FR 55352 (published Sept. 10, 2010).

B. Discussion of the Final Rule

On June 17, 2014, the Department published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) in the Federal Register, inviting public comments for a period of 30 days on a proposal to implement the provisions of Executive Order 13658. See 79 FR 34568 (June 17, 2014). On July 8, 2014, the Department extended the period for filing written comments until July 28, 2014. See 79 FR 38478. More than 6,500 individuals and entities commented on the Department's NPRM. Comments were received from a variety of interested stakeholders, such as labor organizations; contractors and contractor associations; worker advocates, including advocates for people with disabilities; contracting agencies; small businesses; and workers. Some organizations attached the views of some of their individual members. For example, 1,159 individuals joined in comments submitted by Interfaith Worker Justice and the National Women's Law Center submitted 5,127 individual comments.

The Department received many comments, such as those submitted by the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), North America's Building Trades Unions (Building Trades), the National Women's Law Center, Interfaith Worker Justice, Demos, the National Employment Law Project (NELP), and the National Disability Rights Network (NDRN), expressing strong support for the Executive Order and for raising the minimum wage. Many of these commenters, such as Demos, commended the Department's NPRM as a “reasonable and appropriate” implementation of Executive Order 13658. The Building Trades similarly applauded the Department's proposed rule as presenting “a straightforward and comprehensive framework for implementing, policing and enforcing Executive Order 13658.” Although the Professional Services Council (PSC) disagreed with some of the substantive interpretations set forth in the Department's NPRM, it also expressed its appreciation for “the extensive explanatory material” set forth in the preamble to the proposed rule and noted that such information provided “valuable insight into the Department's approach and rationale.”

However, the Department also received submissions from several commenters, including the National Restaurant Association (Association) and the International Franchise Association (IFA), the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (Chamber) and the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), the HR Policy Association, and the Associated Builders and Contractors, Inc. (ABC), expressing strong opposition to the Executive Order and questioning its legality and stated purpose. Comments questioning the legal authority and rationale underlying the Executive Order are not within the purview of this rulemaking action.

The Department also received a number of comments requesting that the President take other executive actions to protect workers on Federal Government contracts. While the Department appreciates such input, comments requesting further executive actions are beyond the scope of this rule and the Department's rulemaking authority.

Finally, the Center for Plain Language (CPL) submitted a comment regarding how the Federal Plain Language Guidelines could improve the general clarity of the final rule. The Department has carefully considered this comment and has endeavored to use plain language in the preamble and regulatory text of the final rule in instances where plain language is appropriate and does not change the substance of the rule. For example, the Department has avoided the use of “prior to,” “pursuant to,” “shall,” “such,” and “thereunder,” where appropriate. In addition, the Department has made an effort to use shorter sentences and paragraphs where possible or appropriate. Some of the suggested changes, however, are not suitable to this final rule. For example, the Department does not find the use of the pronoun “you” or headings in the form of questions to be appropriate here. Section 4(c) of Executive Order 13658 directs the Department to incorporate existing definitions and procedures from the DBA, the SCA, and the FLSA, to the extent practicable. Because the implementing regulations under those statutes do not use the pronoun “you” and do not use questions as headings, the Department has concluded that it would be inconsistent to do so in the final rule.

All other comments, including comments raising specific concerns regarding interpretations of the Executive Order set forth in the Department's NPRM, will be addressed in the following section-by-section analysis of the final rule. After considering all timely and relevant comments received in response to the June 17, 2014 NPRM, the Department is issuing this final rule to implement the provisions of Executive Order 13658.

The Department's final rule, which amends Title 29 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) by adding part 10, establishes standards and procedures for implementing and enforcing Executive Order 13658. Subpart A of part 10 relates to general matters, including the purpose and scope of the rule, as well as the definitions, coverage, and exclusions that the rule provides pursuant to the Order. It also sets forth the general minimum wage requirement for contractors established by the Executive Order, an antiretaliation provision, and a prohibition against waiver of rights. Subpart B establishes the requirements that contracting agencies and the Department must follow to comply with the minimum wage provisions of the Executive Order. Subpart C establishes the requirements that contractors must follow to comply with the minimum wage provisions of the Executive Order. Subparts D and E specify standards and procedures related to complaint intake, investigations, remedies, and administrative enforcement proceedings. Appendix A contains a contract clause to implement Executive Order 13658. 79 FR 9851. Appendix B sets forth a poster regarding the Executive Order minimum wage for contractors with FLSA-covered workers performing work on or in connection with a covered contract.

The following section-by-section discussion of this final rule summarizes the provisions proposed in the NPRM, addresses the comments received on each section, and sets forth the Department's response to such comments for each section.

Subpart A—General

Executive Order 13658 seeks to raise the hourly minimum wage paid by those contractors to workers performing work on covered Federal contracts to: $10.10 per hour, beginning January 1, 2015; and beginning January 1, 2016, and annually thereafter, an amount determined by the Secretary of Labor in accordance with the Order.

Subpart A of part 10 pertains to general matters, including the purpose and scope of the rule, as well as the definitions, coverage, and exclusions that the rule provides pursuant to the Order. Subpart A also includes the Executive Order minimum wage requirement for contractors, an antiretaliation provision, and a prohibition against waiver of rights.

Section 10.1 Purpose and Scope

Proposed §10.1(a) explained that the purpose of the proposed rule was to implement Executive Order 13658 and reiterated statements from the Order that the Federal Government's procurement interests in economy and efficiency are promoted when the Federal Government contracts with sources that adequately compensate their workers. The proposed rule further stated that there is evidence that boosting low wages can reduce turnover and absenteeism in the workplace, while also improving morale and incentives for workers, thereby leading to higher productivity overall. As stated in proposed §10.1(a), it is for these reasons that the Executive Order concludes that raising, to $10.10 per hour, the minimum wage for work performed by parties who contract with the Federal Government will lead to improved economy and efficiency in Government procurement. The NPRM stated that the Department believes that, by increasing the quality and efficiency of services provided to the Federal Government, the Executive Order will improve the value that taxpayers receive from the Federal Government's investment.

The Department received a number of comments asserting that Executive Order 13658 does not promote economy and efficiency in Federal Government procurement and challenging the determinations set forth in the Executive Order that are reflected in proposed §10.1(a). As stated above, comments questioning the President's legal authority to issue the Executive Order are not within the scope of this rulemaking action. To the extent that such comments challenge specific conclusions made by the Department in its economic and regulatory flexibility analyses set forth in the NPRM, those comments are addressed in sections IV and V of the preamble to this final rule. The Department did not receive any other comments addressing proposed §10.1(a) and therefore implements the provision as it was proposed in the NPRM.

Proposed §10.1(b) explained the general Federal Government requirement established in Executive Order 13658 that new contracts with the Federal Government include a clause, which the contractor and any subcontractors shall incorporate into lower-tier subcontracts, requiring, as a condition of payment, that the contractor and any subcontractors pay workers performing work on the contract or any subcontract thereunder at least: (i) $10.10 per hour beginning January 1, 2015; and (ii) an amount determined by the Secretary pursuant to the Order, beginning January 1, 2016, and annually thereafter. Proposed §10.1(b) also clarified that nothing in Executive Order 13658 or part 10 is to be construed to excuse noncompliance with any applicable Federal or State prevailing wage law or any applicable law or municipal ordinance establishing a minimum wage higher than the minimum wage established under the Order. The Department did not receive any comments on proposed §10.1(b) and therefore adopts the provision as proposed.

Proposed §10.1(c) outlined the scope of this proposed rule and provided that neither Executive Order 13658 nor this part creates any rights under the Contract Disputes Act or any private right of action. In the NPRM, the Department explained that it does not interpret the Executive Order as limiting existing rights under the Contract Disputes Act. This provision also restated the Executive Order's directive that disputes regarding whether a contractor has paid the minimum wages prescribed by the Order, to the extent permitted by law, shall be disposed of only as provided by the Secretary in regulations issued under the Order. The provision clarified, however, that nothing in the Order is intended to limit or preclude a civil action under the False Claims Act, 31 U.S.C. 3730, or criminal prosecution under 18 U.S.C. 1001. Finally, this paragraph clarified that neither the Order nor the proposed rule would preclude judicial review of final decisions by the Secretary in accordance with the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. 701 et seq.

The PSC commented on proposed §10.1(c), noting that it concurred with the provision as written but recommended that the Department modify the phrase “create any rights under the Contract Disputes Act” in the first sentence of that provision to “change any rights under the Contract Disputes Act” to recognize that this rule does not impact existing Contract Disputes Act rights. The Department agrees with this comment and, as stated in the NPRM, does not interpret the Executive Order as limiting any existing rights under the Contract Disputes Act. See 79 FR 34571. Accordingly, the Department has provided in §10.1(c) of the final rule that neither Executive Order 13658 nor this part “creates or changes” any rights under the Contract Disputes Act. The Department has also made a technical edit to this section by adding a citation to the Administrative Procedure Act.

Section 10.2 Definitions

Proposed §10.2 defined terms for purposes of this rule implementing Executive Order 13658. Section 4(c) of the Executive Order instructs that any regulations issued pursuant to the Order should “incorporate existing definitions” under the FLSA, the SCA, and the DBA “to the extent practicable and consistent with section 8 of this order.” 79 FR 9852. Most of the definitions provided in the Department's proposed rule were therefore based on either the Executive Order itself or the definitions of relevant terms set forth in the statutory text or implementing regulations of the FLSA, SCA, or DBA. Several proposed definitions adopted or relied upon definitions published by the FARC in section 2.101 of the FAR. 48 CFR 2.101. The Department also proposed to adopt, where applicable, definitions set forth in the Department's regulations implementing Executive Order 13495, Nondisplacement of Qualified Workers Under Service Contracts. 29 CFR 9.2. In the NPRM, the Department noted that, while the proposed definitions discussed in the proposed rule would govern the implementation and enforcement of Executive Order 13658, nothing in the proposed rule was intended to alter the meaning of or to be interpreted inconsistently with the definitions set forth in the FAR for purposes of that regulation.

As a general matter, several commenters, such as Demos and the AFL-CIO, stated that the Department reasonably and appropriately defined the terms of the Executive Order. The AFL-CIO, for example, particularly supported “the inclusive definitions and broad scope of the proposed rule.” Many other individuals and organizations submitted comments supporting, opposing, or questioning specific proposed definitions that are addressed below.

The Department proposed to define the term agency head to mean the Secretary, Attorney General, Administrator, Governor, Chairperson, or other chief official of an executive agency, unless otherwise indicated, including any deputy or assistant chief official of an executive agency or any persons authorized to act on behalf of the agency head. This proposed definition was based on the definition of the term set forth in section 2.101 of the FAR. See 48 CFR 2.101. The CPL suggested that the Department consolidate this definition with the definition set forth for the term Administrator because the NPRM appeared to be using different terms to describe the same concept. The Department disagrees with the CPL's suggested consolidation of these two definitions because the term agency head is used to refer to the head of any executive agency whereas the term Administrator, as used in this part, refers specifically to the head of the Wage and Hour Division, U.S. Department of Labor. Because the Department did not receive any other comments addressing the term agency head, the Department has adopted the definition of that term as it was originally proposed.

The Department proposed to define concessions contract (or contract for concessions) to mean a contract under which the Federal Government grants a right to use Federal property, including land or facilities, for furnishing services. In the NPRM, the Department explained that this proposed definition did not contain a limitation regarding the beneficiary of the services, and such contracts may be of direct or indirect benefit to the Federal Government, its property, its civilian or military personnel, or the general public. See 29 CFR 4.133. The proposed definition included but was not limited to all concessions contracts excluded by Departmental regulations under the SCA at 29 CFR 4.133(b).

Demos expressed its support for the Department's proposed definition of concessions contract, noting that the definition appropriately does not impose restrictions on the beneficiary of services offered by parties to a concessions contract with the Federal Government (i.e., concessions contracts may be of direct or indirect benefit to the Federal Government, its property, its civilian or military personnel, or the general public). Several other commenters expressed concern or confusion regarding application of this definition to specific factual circumstances; such comments are addressed below in the preamble discussion of the coverage of concessions contracts. As the Department received no comments suggesting revisions to the proposed definition of this term, the Department adopts the definition as set forth in the NPRM.

The Department proposed to define contract and contract-like instrument collectively for purposes of the Executive Order as an agreement between two or more parties creating obligations that are enforceable or otherwise recognizable at law. This definition included, but was not limited to, a mutually binding legal relationship obligating one party to furnish services (including construction) and another party to pay for them. The proposed definition of the term contract broadly included all contracts and any subcontracts of any tier thereunder, whether negotiated or advertised, including any procurement actions, lease agreements, cooperative agreements, provider agreements, intergovernmental service agreements, service agreements, licenses, permits, or any other type of agreement, regardless of nomenclature, type, or particular form, and whether entered into verbally or in writing.

The Department explained that the proposed definition of the term contract shall be interpreted broadly to include, but not be limited to, any contract that may be consistent with the definition provided in the FAR or applicable Federal statutes. In the NPRM, the Department noted that this definition shall include, but shall not be limited to, any contract that may be covered under any Federal procurement statute. The Department specifically proposed to note in this definition that contracts may be the result of competitive bidding or awarded to a single source under applicable authority to do so. The proposed definition also explained that, in addition to bilateral instruments, contracts include, but are not limited to, awards and notices of awards; job orders or task letters issued under basic ordering agreements; letter contracts; orders, such as purchase orders, under which the contract becomes effective by written acceptance or performance; and bilateral contract modifications. The proposed definition also specified that, for purposes of the minimum wage requirements of the Executive Order, the term contract included contracts covered by the SCA, contracts covered by the DBA, and concessions contracts not otherwise subject to the SCA, as provided in section 7(d) of the Executive Order. See 79 FR 9853. The proposed definition of contract discussed herein was derived from the definition of the term contract set forth in Black's Law Dictionary (9th ed. 2009) and §2.101 of the FAR (48 CFR 2.101), as well as the descriptions of the term contract that appear in the SCA's regulations at 29 CFR 4.110-.111, 4.130. The Department also incorporated the exclusions from coverage specified in section 7(f) of the Executive Order and provided that the term contract does not include grants; contracts and agreements with and grants to Indian Tribes under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (Pub. L. 93-638), as amended; or any contracts or contract-like instruments expressly excluded by §10.4.

The Department noted that the mere fact that a legal instrument constitutes a contract under this definition does not mean that the contract is subject to the Executive Order. The NPRM explained that, in order for a contract to be covered by the Executive Order and the proposed rule, the contract must qualify as one of the specifically enumerated types of contracts set forth in section 7(d) of the Order and proposed §10.3. For example, although a cooperative agreement would be considered a contract pursuant to the Department's proposed definition, a cooperative agreement would not be covered by the Executive Order and this part unless it was subject to the DBA or SCA, was a concessions contract, or was entered into “in connection with Federal property or lands and related to offering services for Federal employees, their dependents, or the general public.” 79 FR 9853. In other words, the NPRM explained that this part would not apply to cooperative agreements that did not involve providing services for Federal employees, their dependents, or the general public.

Several individuals and entities submitted comments expressing their support for the Department's proposed definition of the terms contract and contract-like instrument. NELP and the eight organizations that joined in its comment, for example, stated that the proposed definition “fairly reflect[s] the increasing complexity of leasing and contracting relationships between the Federal Government and the private sector.” The AFL-CIO similarly commended the Department's proposed definition because “it is consistent both with the Executive Order and because it tracks the definitions contained in the SCA and DBA. . . . The proposal appropriately seeks to include the full range of contracts and other government procurement arrangements so as to effectuate the purposes of the Executive Order.”

However, the Department received several comments, such as those submitted by the Associated General Contractors of America (AGC), the Chamber/NFIB, the Equal Employment Advisory Council (EEAC), and the Association/IFA, expressing confusion or concern regarding the breadth of the Department's proposed definition of the terms contract and contract-like instrument. The National Ski Areas Association (NSAA), for example, described this proposed definition as “all-encompassing” and “remarkably broad.” NSAA asserted that the proposed definition of the term contract was so broad that it could extend to cover “any agreement with a federal agency” and could “include even those hotels that accept a GSA room rate for government employees.”

The PSC similarly criticized the Department's “very broad” proposed definition and contended that it would cover situations and business relationships that are not subject to the FAR or the SCA's regulations, thus generating confusion among contractors. The PSC asserted that the proposed definition also “over-scopes” the term contract to include transactions, such as notices of awards that are not “mutually binding legal relationships.” The PSC further stated that the proposed definition of the term would cover instruments such as blanket purchase agreements, task orders, and delivery orders that it does not regard as “contracts.” The PSC thus urged the Department to adopt the definition of the term contract set forth in the FAR for purposes of covering Federal procurement transactions. The EEAC criticized the Department's proposed definition for including “verbal agreements,” and asserted that it is difficult to imagine how a proposed contract clause could be included in a verbal agreement. It further observed that the proposed definition would appear to cover any lease for space under the General Services Administration's (GSA) outlease program as well as any license or permit to use Federal land, including a permit to conduct a wedding on Federal property.

As a threshold matter, the Department notes that its proposed definition of the terms contract and contract-like instrument was primarily derived from the definitions of those terms in the FAR and the SCA's regulations and thus it should not have been wholly unfamiliar or unduly confusing to contractors. See 48 CFR 2.101; 29 CFR 4.110-.111, 4.130. For example, the PSC criticized the proposed definition for its inclusion of “notices of awards,” which the PSC argues are not “mutually binding legal relationships.” However, this language is taken verbatim from the FAR definition of the term contract that the PSC itself urges the Department to adopt. See 48 CFR 2.101 (defining the term contract as “a mutually binding legal relationship” and specifically stating that “contracts include (but are not limited to) awards and notices of awards”).

Although the Department relied heavily on the FAR's definition of the term contract, the Department must reject the suggestion that it wholly adopt the FAR definition of the term because the term contract as used in the Executive Order applies to both procurement and non-procurement legal arrangements whereas the FAR definition only applies to procurement contracts. For that reason, the Department has also relied upon the Department's interpretation of the term “contract” under the SCA. For example, the proposed definition includes “verbal agreements” because the SCA's regulations specifically provide that the mere fact that an agreement is not written does not render such contract outside the scope of the SCA's coverage, see 29 CFR 4.110, even though the SCA mandates inclusion of a written contract clause. The inclusion of verbal agreements in the definition of the terms contract and contract-like instrument helps to ensure that coverage of the Executive Order can extend to situations where contracting parties, for whatever reason, rely on an oral agreement rather than a written contract. Although such instances are likely to be exceptionally rare, workers should not be deprived of the Executive Order minimum wage merely because the contracting parties neglected to formally memorialize their mutual agreement in an executed written contract.

With respect to all comments regarding the general breadth of the proposed definition of the terms contract and contract-like instrument, the Department notes that its proposed definition is intentionally all-encompassing. The proposed definition of these terms could indeed be applied to an expansive range of different types of legal arrangements, including purchase and task orders; the use of the term “contract-like instrument” in the Executive Order underscores that the Order was intended to be of potential applicability to virtually any type of agreement with the Federal Government that is contractual in nature. Importantly, however, the NPRM carefully explained that “the mere fact that a legal instrument constitutes a contract under this definition does not mean that such contract is subject to the Executive Order.” 79 FR 34572.

In order for a legal instrument to be covered by the Executive Order, the instrument must satisfy all of the following prongs: (1) It must qualify as a contract or contract-like instrument under the definition set forth in this part; (2) it must fall within one of the four specifically enumerated types of contracts set forth in section 7(d) of the Order and §10.3 of this part; and (3) it must be a “new contract” pursuant to the definition provided in §10.2. (Moreover, in order for the minimum wage protections of the Executive Order to actually extend to a particular worker on a covered contract, that worker's wages must be governed by the DBA, SCA, or FLSA.) For example, although an agreement between a contracting agency and a hotel pursuant to which the hotel accepts the GSA room rate for Federal Government workers would likely be regarded as a “contract” or “contract-like instrument” under the Department's proposed definition, such an agreement would not be covered by the Executive Order and this part because it is not subject to the DBA or SCA, is not a concessions contract, and is not entered into in connection with Federal property or lands. Similarly, a permit issued by the National Park Service (NPS) to an individual for purposes of conducting a wedding on Federal land would qualify as a “contract” or “contract-like instrument” but would not be subject to the Executive Order because it would not be a contract covered by the SCA or DBA, a concessions contract, or a contract in connection with Federal property related to offering services to Federal employees, their dependents, or the general public. The Department believes that this basic test for contract coverage was clearly stated in the NPRM, but has endeavored to provide additional clarification and examples of covered contracts in its preamble discussion of the coverage provisions set forth at §10.3 in this final rule.

Several other commenters, including AGC, requested that the Department separately define the term contract-like instrument and provide examples of contract-like instruments because the regulated community is generally unfamiliar with the term. The EEAC generally observed that the term contract-like instrument is not used in the FAR or the prevailing wage statutes with which most government contractors are familiar and thus the term has generated considerable confusion in the regulated community. Fortney and Scott, LLC (FortneyScott) similarly requested that the Department clarify the definition of a contract-like instrument. It asserted that all of the examples of “contract-like instruments” set forth in the NPRM would in fact qualify as “contracts” and therefore asked whether there would be any instruments that would be deemed to be “contract-like instruments” that would not also be considered “contracts.” FortneyScott suggested that the Department should expressly state in the final rule that there are no “contract-like instruments” subject to the Executive Order other than those that would be covered by the definition of “contract.”

The Department acknowledges that the term contract-like instrument is not used in the FLSA, SCA, DBA, or FAR. For this reason, the Department has defined the term collectively with the well-known term contract in a manner that should be generally known and understood by the contracting community. As noted above, several commenters accurately observed that the Department's proposed definition of these terms is broad. The use of the term “contract-like instrument” in the Executive Order reflects that the Order is intended to cover all arrangements of a contractual nature, including those arrangements that may not be universally regarded as a “contract.” For example, the term contract-like instrument would encompass Forest Service permits that “possess contract characteristics,” Son Broadcasting, Inc. v. United States, 52 Fed. Cl. 815, 823 (Ct. Cl. 2002), and that use “contract-like language.” Meadow-Green Wildcat Corp. v. Hathaway, 936 F.2d 601, 604 (1st Cir. 1991). The large number of specific comments that the Department received regarding the coverage of “contracts for concessions” and “contracts in connection with Federal property” underscores the importance of the term “contract-like instrument” in the Executive Order; as the EEAC itself observed, “[e]mployers may not think of these arrangements as contracts at all, and indeed may be surprised to learn that the new minimum wage mandate applies.” For this precise reason, the Executive Order utilized the term “contract-like instrument” to help clarify that its minimum wage requirements are broadly applicable to all contractual arrangements so long as such arrangements fall within one of the four specifically enumerated types of arrangements set forth in section 7(d) of the Order. The Department acknowledges that the term contract-like instrument does not apply to an arrangement or an agreement that is truly not contractual. However, the use of such term helps to emphasize that the Executive Order was intended to sweep broadly to apply to concessions agreements and agreements in connection with Federal property or lands and related to offering services, regardless of whether the parties involved typically consider such arrangements to be “contracts” and regardless of whether such arrangements are characterized as “contracts” for purposes of the specific programs under which they are administered. Moreover, the Department believes that the Executive Order's use of the term contract-like instrument is intended to prevent disputes or extended discussions between contracting agencies and contractors regarding whether a particular legal instrument qualifies as a “contract” for purposes of coverage by the Order and this part. The broad definition set forth in this rule will help facilitate more efficient determinations by contractors, contracting officers, and the Department as to whether a particular legal arrangement is covered. The Department thus declines to separately define the term contract-like instrument as suggested by some commenters because the term is best understood contextually in conjunction with the well-known term contract.

The United States Department of Agriculture's Forest Service (FS) commented that the Department should consolidate the definition of the terms contract and contract-like instrument with the definition of the term concessions contract because it believes that the definition of concessions contract is subsumed in the more general definition of contract. Although the Department agrees that the definition of the term contract is relevant to determining whether a legal instrument qualifies as a “contract for concessions,” the Department continues to believe that a separate definition is necessary to inform the regulated community about the meaning of the term “contract for concessions.” As noted above, commenters such as Demos expressed their strong support for the proposed definition of the term “contract for concessions.” The need for this specific and separate definition is underscored by the large number of comments that the Department received regarding the coverage of concessions contracts and contracts in connection with Federal property or lands. The Department addresses the specific concerns raised regarding the coverage of concessions contracts in the preamble discussion of coverage provisions below.

Several other commenters, including the America Outdoors Association (AOA) and the Association/IFA, urged the Department to include separate definitions of the terms subcontract and subcontractor in the final rule. In the NPRM, the Department stated that the proposed definition of the term contract broadly included all contracts and any subcontracts of any tier thereunder and also provided that the term contractor referred to both a prime contractor and all of its subcontractors of any tier on a contract with the Federal Government. The AOA and the Association/IFA expressed confusion regarding the “flow-down” provisions of the Executive Order and suggested that the Department could help to clarify coverage of subcontracts by expressly defining that term.

The applicability of the Executive Order to subcontracts is addressed in greater detail in the discussion of the rule's coverage provisions below, but with respect to these commenters' specific proposal to separately define the terms subcontract and subcontractor, the Department declines to set forth definitions of those terms in the final rule because it could generate significant confusion for contracting agencies, contractors, and workers. The Department notes that many commenters, including the Association/IFA itself, strongly urged the Department to align its definitions and coverage provisions with those set forth in the SCA, the DBA, and the FAR to ensure compliance and to minimize confusion. Neither the FAR nor the regulations implementing the DBA or SCA provide independent definitions of the terms “subcontract” and “subcontractor.” The SCA's regulations, for example, simply provide that the definition of the term “contractor” includes a subcontractor whose subcontract is subject to provisions of the SCA. See 29 CFR 4.1a(f).

As with the SCA and DBA, all of the provisions of the Executive Order that are applicable to covered prime contracts and contractors apply with equal force to covered subcontracts and subcontractors, except for the value threshold requirements set forth in section 7(e) of the Order that only pertain to prime contracts. The final rule provides more clarity with respect to the rule's flow-down provisions and subcontractor coverage and liability below. For these reasons and to avoid using unnecessary and duplicative terms throughout this part, the Department therefore will continue to utilize the term contract to refer to all contracts and any subcontracts thereunder and use the term contractor to refer to a prime contractor and all of its subcontractors in the final rule, unless otherwise noted.

The Department has carefully considered all of the comments received on the proposed definition of the terms contract and contract-like instrument but, for the reasons set forth above, ultimately declines to make any of the suggested changes. However, the Department has modified the proposed definition of contract to delete reference to the exclusions from coverage specified in section 7(f) of the Executive Order (i.e., grants; contracts and agreements with and grants to Indian Tribes under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (Pub. L. 93-638), as amended; or any contracts or contract-like instruments expressly excluded by §10.4). As the Department has explained throughout this rule, the mere fact that an agreement qualifies as a “contract” under this definition does not necessarily mean that the agreement is covered by the Order. Accordingly, the Department has determined that its proposed reference to the exclusionary provisions of the Order in this definition is unnecessary and potentially confusing for the public. The Department has also made a clarifying edit to the definition of contract to reflect application of the Executive Order to contracts in connection with Federal property or land and related to offering services for Federal employees, their dependents, or the general public. Other than these changes, the Department adopts the definition as proposed in the NPRM.

The Department proposed to substantially adopt the definition of contracting officer in section 2.101 of the FAR, which means a person with the authority to enter into, administer, and/or terminate contracts and make related determinations and findings. The term included certain authorized representatives of the contracting officer acting within the limits of their authority as delegated by the contracting officer. See 48 CFR 2.101. The Department did not receive any comments on its proposed definition of this term; the final rule therefore adopts the definition as proposed.

The Department defined contractor to mean any individual or other legal entity that (1) directly or indirectly (e.g., through an affiliate), submits offers for or is awarded, or reasonably may be expected to submit offers for or be awarded, a Government contract or a subcontract under a Government contract; or (2) conducts business, or reasonably may be expected to conduct business, with the Government as an agent or representative of another contractor. In the NPRM, the Department noted that the term contractor refers to both a prime contractor and all of its subcontractors of any tier on a contract with the Federal Government. This proposed definition incorporated relevant aspects of the definitions of the term contractor in section 9.403 of the FAR, see 48 CFR 9.403; the SCA's regulations at 29 CFR 4.1a(f); and the Department's regulations implementing Executive Order 13495, Nondisplacement of Qualified Workers Under Service Contracts at 29 CFR 9.2. This definition included lessors and lessees, as well as employers of workers performing on or in connection with covered Federal contracts whose wages are computed pursuant to special certificates issued under 29 U.S.C. 214(c). The Department noted that the term employer is used interchangeably with the terms contractor and subcontractor in this part. The proposed rule also explained that the U.S. Government, its agencies, and its instrumentalities are not considered contractors, subcontractors, employers, or joint employers for purposes of compliance with the provisions of Executive Order 13658.

The Department received several comments on its proposed definition of the term contractor. The PSC, for example, contended that the proposed definition improperly covers entities that are not subject to the Executive Order, the FAR, or the SCA's regulations. In its comment, the PSC observed that the proposed definition covers an entity that “submits an offer or reasonably may be expected to submit offers for” a government contract and asserted that it is “not aware of any federal procurement provision that applies to entities who ‘may be expected to submit offers’” and urged the Department to delete this language. The Association/IFA similarly criticized the Department's proposed definition of the term contractor as including prospective bidders on a government contract “with no explanation provided in the preamble.” The Association/IFA further urged the Department to define specific words that appear in the proposed definition of contractor, such as “affiliate” and “indirectly,” and to clarify what it means to “indirectly” submit offers. The Association/IFA also challenged the proposed definition as including an “exceedingly broad” category of entities because it would apply to entities such as law firms that “reasonably may be expected to conduct business . . . with the Government as an agent or representative of another contractor.” The Association/IFA expressed concern that the Department's proposed definition could potentially cover “hundreds of thousands of entities that never before considered themselves ‘government contractors'” and would need to ascertain what, if any, legal obligations they have under the Executive Order. The National Industry Liaison Group (NILG) similarly requested that the Department narrow its proposed definition of the term contractor to exclude prospective and former Federal contractors.

The Department notes that all of the proposed definitional language to which the PSC, the Association/IFA, and the NILG object is taken verbatim from the FAR's definition of the term contractor. See 48 CFR 9.403. The Department proposed this definition, in part, because it believed that the definition would be of general familiarity to contractors. Moreover, the proposed definition purposely included both prospective and former contractors because, like section 9.403 of the FAR, this final rule also sets forth standards regarding the debarment, suspension, and ineligibility of contractors.

However, in light of the comments received by the Department expressing concern and confusion regarding the breadth of the proposed definition of the term contractor, the Department has decided to simplify the definition in the final rule to assist the general public in understanding coverage of the Executive Order. In the final rule, the Department has therefore deleted the first sentence of the definition derived from the FAR and instead defines contractor to mean any individual or other legal entity that is awarded a Federal Government contract or subcontract under a Federal Government contract. The Department has therefore removed the proposed definition's reference to prospective contractors and has eliminated use of terms such as “affiliate” and “indirectly,” which apparently confused several commenters. However, the Department notes that, despite the removal of language regarding prospective contractors from this definition, such a deletion has no impact on the suspension and debarment provisions of the final rule. In other words, an individual that is awarded a Federal Government contract may be debarred pursuant to §10.52 if he or she has disregarded obligations to workers or subcontractors under the Executive Order or this part.

Importantly, the Department notes that the mere fact that an individual or entity qualifies as a contractor under the Department's definition does not mean that such an entity has any legal obligations under the Executive Order. A contractor only has obligations under the Executive Order if it has a contract with the Federal Government that is specifically covered by the Order. Thus, while an individual that is awarded a contract with the Federal Government will qualify as a “contractor” pursuant to the Department's definition, that individual will only be subject to the minimum wage requirements of the Executive Order if he or she is awarded a “new” contract that falls within the scope of one of the four specifically enumerated categories of contracts covered by the Order.

Other than the revisions to the first sentence of the proposed definition of the term contractor explained above, the Department has retained the remainder of the proposed definition, which incorporates relevant aspects of the definition from the SCA's regulations at 29 CFR 4.1a(f) and the Department's regulations implementing Executive Order 13495, Nondisplacement of Qualified Workers Under Service Contracts at 29 CFR 9.2. As in the proposed rule, the Department thus explains that the term contractor refers to both a prime contractor and all of its subcontractors of any tier on a contract with the Federal Government. The Department also notes that the term contractor includes lessors and lessees, as well as employers of workers performing on covered Federal contracts whose wages are calculated pursuant to special certificates issued under 29 U.S.C. 214(c). Finally, as stated in the NPRM, the Department explains that the term employer is used interchangeably with the terms contractor and subcontractor in various sections of this part and that the U.S. Government, its agencies, and instrumentalities are not contractors, subcontractors, employers, or joint employers for purposes of compliance with the provisions of the Executive Order.

The PSC commented on the portion of the proposed definition of contractor that states that neither the U.S. Government nor its agents are contractors or employers for purposes of the rule and stated that it has not yet had an opportunity to research whether the Department has the authority to make “such a binding declaration by regulation” or the potential effects of such a statement. The Department notes that this language identified by the PSC is taken directly from the SCA's definition of the term contractor, see 29 CFR 4.1a(f), and merely reflects that for purposes of this Executive Order the Federal Government does not contract with itself or enter into employment relationships with the contractors with whom it conducts business.

Finally, the Association/IFA suggested that the Department define the term “Government contract” because it is used in the definition of contractor. The Department disagrees with this comment because this part already contains definitions of the term Federal Government and contract. Because other commenters such as the CPL have urged the Department to avoid creating duplicative definitions and the Department believes that readers of this part already have clear guidance about what types of agreements qualify as contracts with the Federal Government, the Department declines to make this suggested revision.

For the reasons explained above, the Department has revised the first sentence of the definition of the term contractor as proposed in the NPRM to assist the general public in understanding coverage of the Executive Order, but has retained the remainder of the proposed definition in the final rule.

The Department proposed to define the term Davis-Bacon Act to mean the Davis-Bacon Act of 1931, as amended, 40 U.S.C. 3141 et seq., and its implementing regulations. Because the Department did not receive any comments on this proposed definition, the Department adopts the proposed definition in this final rule.

In the NPRM, the Department defined executive departments and agencies that are subject to Executive Order 13658 by adopting the definition of executive agency provided in section 2.101 of the FAR. 48 CFR 2.101. The Department therefore interpreted the Executive Order to apply to executive departments within the meaning of 5 U.S.C. 101, military departments within the meaning of 5 U.S.C. 102, independent establishments within the meaning of 5 U.S.C. 104(1), and wholly owned Government corporations within the meaning of 31 U.S.C. 9101. The Department did not interpret this definition as including the District of Columbia or any Territory or possession of the United States. No comments were received on this proposed definition; the final rule therefore adopts the definition as set forth in the NPRM.

The Department defined the term Executive Order minimum wage as a wage that is at least: (i) $10.10 per hour beginning January 1, 2015; and (ii) beginning January 1, 2016, and annually thereafter, an amount determined by the Secretary pursuant to section 2 of Executive Order 13658. This definition was based on the language set forth in section 2 of the Executive Order. 79 FR 9851-52. No comments were received on this proposed definition; accordingly, this definition is adopted in the final rule.

The Department proposed to define Fair Labor Standards Act as the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, as amended, 29 U.S.C. 201 et seq., and its implementing regulations. The Department did not receive any comments on this proposed definition and therefore adopts the definition as proposed, except that it has added the acronym FLSA to the definition.

The term Federal Government was defined in the NPRM as an agency or instrumentality of the United States that enters into a contract pursuant to authority derived from the Constitution or the laws of the United States. This proposed definition was based on the definition of Federal Government set forth in 29 CFR 9.2, but eliminated the term “procurement” from that definition because Executive Order 13658 applies to both procurement and non-procurement contracts covered by section 7(d) of the Order. Consistent with the SCA, the proposed definition of the term Federal Government included nonappropriated fund instrumentalities under the jurisdiction of the Armed Forces or of other Federal agencies. See 29 CFR 4.107(a). For purposes of the Executive Order and this part, the Department's proposed definition did not include the District of Columbia or any Territory or possession of the United States. The Department did not receive any comments on the proposed definition of Federal Government and thus adopts the definition as set forth in the NPRM with one modification. For the reasons explained in the NPRM and set forth below, independent regulatory agencies within the meaning of 44 U.S.C. 3502(5) are not subject to the Executive Order or this part. The Department has therefore made a clarifying edit to this definition to reflect that, for purposes of the Executive Order, independent regulatory agencies are not included in the definition of Federal Government.

The Department proposed to define the term independent agencies, for the purposes of Executive Order 13658, as any independent regulatory agency within the meaning of 44 U.S.C. 3502(5). Section 7(g) of the Executive Order states that “[i]ndependent agencies are strongly encouraged to comply with the requirements of this order.” The Department interpreted this provision to mean that independent agencies are not required to comply with this Executive Order. This proposed definition was therefore based on other Executive Orders that similarly exempt independent regulatory agencies within the meaning of 44 U.S.C. 3502(5) from the definition of agency or include language requesting that they comply. See, e.g., Executive Order 13636, 78 FR 11739 (Feb. 12, 2013) (defining agency as any executive department, military department, Government corporation, Government-controlled operation, or other establishment in the executive branch of the Government but excluding independent regulatory agencies as defined in 44 U.S.C. 3502(5)); Executive Order 13610, 77 FR 28469 (May 10, 2012) (same); Executive Order 12861, 58 FR 48255 (September 11, 1993) (“Sec. 4 Independent Agencies. All independent regulatory commissions and agencies are requested to comply with the provisions of this order.”); Executive Order 12837, 58 FR 8205 (Feb. 10, 1993) (“Sec. 4. All independent regulatory commissions and agencies are requested to comply with the provisions of this order.”). The Department did not receive any comments on the proposed definition of this term and therefore adopts the definition as proposed in this final rule.

The Department proposed to define the term new contract as a contract that results from a solicitation issued on or after January 1, 2015, or a contract that is awarded outside the solicitation process on or after January 1, 2015. The proposed definition noted that this term includes both new contracts and replacements for expiring contracts provided that the contract results from a solicitation issued on or after January 1, 2015, or is awarded outside the solicitation process on or after January 1, 2015. This language was based on section 8 of the Executive Order, 79 FR 9853, and was consistent with the convention set forth in section 1.108(d) of the FAR, 48 CFR 1.108(d). The PSC commented that it supports the proposed definition of this term. In response to several comments requesting clarification of the Executive Order's applicability to new contracts, the Department has revised the definition of “new contract” provided in §10.2 of the proposed rule, as explained below in the preamble discussion of the “new contract” coverage provisions set forth at §10.3.

Proposed §10.2 defined the term option by adopting the definition set forth in section 2.101 of the FAR, which provides that the term option means a unilateral right in a contract by which, for a specified time, the Federal Government may elect to purchase additional supplies or services called for by the contract, or may elect to extend the term of the contract. See 48 CFR 2.101. As noted above, many commenters expressed confusion or concern with the Department's discussion of the coverage of new contracts, including its proposed interpretation that the exercise of an option clause by the Federal Government does not constitute a “new contract” for purposes of the Executive Order. All such comments are addressed below in the preamble discussion of the coverage provisions set forth at §10.3.

Several other commenters, including Bond, Schoeneck, and King, PLLC, and the Civil Works Program of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), observed that the Department's proposed definition of the term option refers only to a unilateral contractual right held by the Federal Government; these commenters questioned whether the Department would also include situations in which a contractor exercises a unilateral right to extend the term of a contact within its definition of an option. The USACE noted, for example, that many of its leases of Federal lands to third parties contain options for renewal that provide the lessee with the unilateral right to renew the lease with all terms and conditions of the existing lease, except that they occasionally provide for increased rent and are subject to USACE's discretion to terminate the lease or decline renewal of the lease for non-compliance with the terms and conditions of the agreement.

In response to these comments, the Department notes that its proposed definition of the term option, which solely refers to a unilateral contractual right exercised by the Federal Government, is taken directly from the FAR. See 48 CFR 2.101. The Department chose to utilize this definition in order to provide clarity and consistency with well-established contracting concepts to the regulated community. The Department understands that it is rare for the Federal Government to enter into agreements under which a contractor would have the unilateral right to extend the term of the contract without entering into bilateral negotiations with the contracting agency. Insofar as such a situation may arise in which a contractor holds a unilateral right to extend the contract, however, the Department believes that the interests of the Executive Order are best effectuated by adhering to its conclusion that only the unilateral exercise of a pre-negotiated option clause by the Federal Government itself falls outside the scope of the Order; if a contractor unilaterally elects to exercise an option period after January 1, 2015, that option period may be subject to the minimum wage requirements of the Order. After thorough review and consideration of these comments, the Department has decided to implement the definition as proposed in the NPRM without modification.

The Department proposed to define the term procurement contract for construction to mean a contract for the construction, alteration, or repair (including painting and decorating) of public buildings or public works and which requires or involves the employment of mechanics or laborers, and any subcontract of any tier thereunder. The proposed definition included any contract subject to the provisions of the DBA, as amended, and its implementing regulations. This proposed definition was derived from language found at 40 U.S.C. 3142(a) and 29 CFR 5.2(h). The Department did not receive any comments on this proposed definition and it is therefore adopted as set forth in the NPRM.

The Department proposed to define the term procurement contract for services to mean a contract the principal purpose of which is to furnish services in the United States through the use of service employees, and any subcontract of any tier thereunder. This proposed definition included any contract subject to the provisions of the SCA, as amended, and its implementing regulations. This proposed definition was derived from language set forth in 41 U.S.C. 6702(a), 29 CFR 4.1a(e), and 29 CFR 9.2. No comments were submitted on this definition; accordingly, the Department implements the definition as proposed.

The Department proposed to define the term Service Contract Act to mean the McNamara-O'Hara Service Contract Act of 1965, as amended, 41 U.S.C. 6701 et seq., and its implementing regulations. See 29 CFR 4.1a(a). The Department did not receive any comments on the proposed definition of this term and thus adopts the definition as proposed for purposes of the final rule.

In the NPRM, the term solicitation was defined to mean any request to submit offers or quotations to the Federal Government. This definition was based on the language found at 29 CFR 9.2. The Department broadly interpreted the term solicitation to apply to both traditional and nontraditional methods of solicitation, including informal requests by the Federal Government to submit offers or quotations. In its comment, the PSC did not object to the proposed definition of this term as set forth in the regulatory text itself, but stated that the NPRM's preamble discussion of this term reflected that the Department intended to cover “informal requests” by the Federal Government to submit offers or quotations. The PSC urged the Department to reject this interpretation because it could be construed to inappropriately cover “requests for information” whereby agencies seek information from the public without providing any commitment to issuing solicitations or making awards. The PSC similarly contended that this interpretation of “solicitation” could even be deemed to apply to informal conversations with Federal workers. In response to the PSC's concerns, the Department has clarified that requests for information issued by Federal agencies and informal conversations with Federal workers are not “solicitations” for purposes of the Executive Order.

The final rule therefore adopts the definition as proposed, except that it clarifies that the term solicitation also includes any request to submit “bids” to the Federal Government. The Department believes that the NPRM was clear that “bids” were included within its reference to “offers or quotations,” but has determined that it would be helpful to the regulated community to include the more colloquially used term “bids” in the final rule.

The Department adopted in the proposed rule the definition of tipped employee in section 3(t) of the FLSA, that is, any employee engaged in an occupation in which he or she customarily and regularly receives more than $30 a month in tips. See 29 U.S.C. 203(t). The NPRM explained that, for purposes of the Executive Order, a worker performing on or in connection with a contract covered by the Executive Order who meets this definition is a tipped employee. One commenter, the CPL, criticized the Department for defining the term tipped employee twice in its proposed rule—first in the “definitions” section at proposed §10.2 and subsequently in the section addressing contractor requirements with respect to tipped employees at proposed §10.28(b)(1). The CPL added that the definition provided in proposed §10.2 was “incomplete” because it did not include the additional clarifications provided in proposed §10.28(b)(1). In response, the Department notes that the two definitions are consistent and believes that keeping the definitions of “tipped employee” in both sections is appropriate to the extent that doing so obviates the need for contractors to cross reference between sections when attempting to understand their obligations to tipped employees. For that reason, the Department adopts the definition of “tipped employee” in §10.2 as it was originally proposed.

In proposed §10.2, the Department defined the term United States by adopting the definition set forth in 29 CFR 9.2, which provides that the term means the United States and all executive departments, independent establishments, administrative agencies, and instrumentalities of the United States, including corporations of which all or substantially all of the stock is owned by the United States, by the foregoing departments, establishments, agencies, instrumentalities, and including nonappropriated fund instrumentalities. The proposed definition also incorporated the definition of the term that appears in the FAR at 48 CFR 2.101, which explains that when the term is used in a geographic sense, the United States means the 50 States and the District of Columbia. The Department's proposed rule did not adopt any of the exceptions to the definition of this term that are set forth in the FAR. No comments were received on this proposed definition and it is therefore implemented in the final rule.

The Department proposed to define wage determination as including any determination of minimum hourly wage rates or fringe benefits made by the Secretary pursuant to the provisions of the SCA or the DBA. This term included the original determination and any subsequent determinations modifying, superseding, correcting, or otherwise changing the provisions of the original determination. The proposed definition was derived from 29 CFR 4.1a(h) and 29 CFR 5.2(q). The Department did not receive any comments on this proposed definition and thus adopts it as proposed for the final rule.